Michael Moore’s new film, “Where to Invade Next,” suggests that Moore is better suited to protect our nation than our politicians. While the film poses the idea as a satirical farce, recent events in Flint, Michigan, suggest that it may well be true.

Nearly two years ago Flint started to get its water from a local river rather than Lake Huron in a scheme to save money. Almost immediately it became clear that the switch meant unhealthy water. Despite evidence that the water was contaminated, Republican Gov. Rick Snyder and his appointed emergency manager ignored the health of Flint residents in favor of saving costs.

Now there is evidence that Flint residents are suffering from lead poison, higher rates of Legionnaires Disease, and a host of other health issues.

While the story got some media attention, especially from Rachel Maddow, it was Michael Moore’s call to action via an online open letter to Snyder and a petition with the hashtag #ArrestGovSnyder that prompted real and swift action.

Moore launched his website on Jan. 6. One week later, Gov. Snyder sent in the National Guard to help with the disaster and had been hit with a class action lawsuit.

While it is clear that a host of people worked hard to get support for the residents of Flint, there is little question that Moore’s activism has been crucial. Snyder hasn’t been arrested yet and the town is still suffering, but Moore is still fighting for justice.

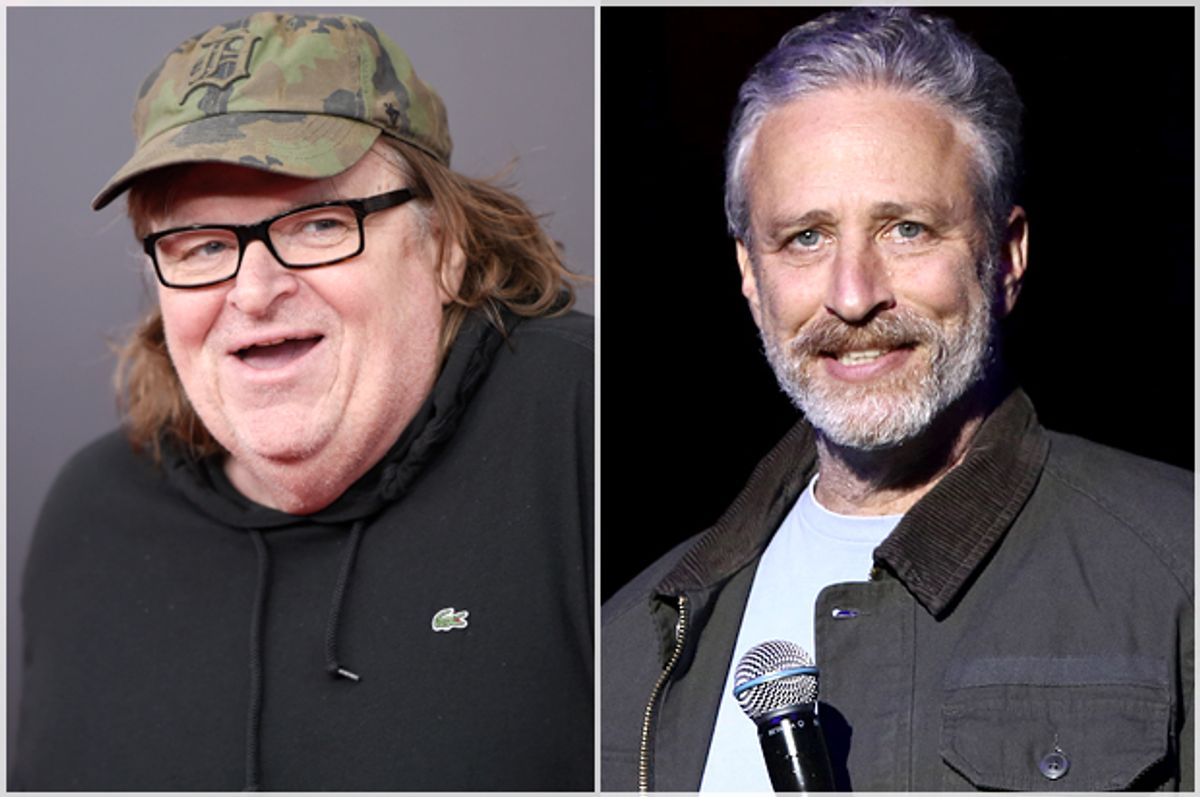

Moore’s involvement with raising national attention to this issue is indicative of a growing trend where political satirists are increasingly involved with direct political action. Recall when Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart held a Rally on the National Mall in 2010 to encourage midterm voting. Or when John Oliver motivated viewers to crash the FCC website over “net neutrality.” Or when the Yes Men posed as Dow Chemical representatives who had decided to take full responsibility for the tragedy Bhopal, India. And don’t forget that much of Occupy Wall Street had a satirical tone –including staging a bullfight. OWS also offered satirical interventions from comedians like Lee Camp. And those are just a few examples.

While satirical activism has a long history, it remains clear that it is playing a greater role in raising public awareness for major social issues. As the media has become a circus and politicians seem like clowns, it is the comedians who appear to be the ones taking the issues in our nation seriously.

Not only are comedians voted as more trusted journalists than actual journalists, but it’s comedians who are influencing politics rather than just making jokes about it.

And that brings us back to Flint. Because, it could be argued, that that’s where much of this all began. Flint was the location for Moore’s first film, “Roger and Me,” which focused on GM’s decision to close most of its plants in Flint and move those jobs outside of the country.

The key, though, is that the film was not a straight documentary. Rather than tell the story straight, it used irony and comedy. In fact it defined a new genre—the mockumentary. Unlike other “fake” documentaries, Moore’s was unique in its combination of humor and political insight. In 2013 it was selected for preservation by the United States Film Registry of the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Sure, shows like “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” were a major force for political action in the '60s and, sure, our nation has a long history of blending satire and politics that goes back to Ben Franklin, but it is really Moore’s debut film that created a new genre that blended satire, silliness, politics, activism and public impact. Moore’s successful ability to entertain, enlighten and engage brought documentaries back to movie theaters and his films have broken a number of box office records.

“Roger and Me” was a truly innovative form. Its creative brilliance was its ability to blend a tragic story about the devastating effects of transnational capitalism on U.S. labor with a farcical tale of Moore’s efforts to interview GM chairman Roger Smith. Viewers learned about the real human cost to the greedy profit model of companies like GM, but they did so through the comedic release of satire and irony.

Satire is a form of comedy that has always been used to point out abuses of power. But it is worth noting that Moore’s first film came out in 1989 just as our nation was beginning to enter a unique moment of social crisis. It came out the same year that the Berlin Wall came down, the Soviet Union collapsed, and free-market capitalism took the globe by storm. In the U.S. this was the era when many politicians worked to protect the interests of neoliberal capital more than the people in their own constituencies.

The story of Flint is the story of what happens when profits are more important than people. What Moore captured in 1989 was a clear prelude to what is happening there today. First Flint residents lost their jobs. Twenty-five years later they have lost their water and their health. There are 10 dead today from Legionnaire’s disease in Flint and countless others with serious illnesses from contaminated water.

It’s a story of human loss that Moore is now no longer telling with humor. Instead, his open letter to Snyder is simply filled with irony, sarcasm and righteous anger. Moore focuses on painting Snyder as a criminal who should be in prison. He snarkily gives Snyder a science lesson and he ironically offers him a Gateway computer for his cell, but none of the humor is meant to detract from the goal of sending the governor to jail.

We have seen other political comedians pull away from overt humor when the cause has demanded it. Colbert dropped all joking when he advocated for South Carolina schoolteachers and migrant workers. Stewart similarly left humor aside when he took up the cause of healthcare for the 9/11 first responders.

What this shows us is that we have experienced a wave of satirical activists who use irony and comedy to seriously fight for what they believe in. And when necessary, they will play it straight to make their points. For instance, the photo of Moore used on his #ArrestGovSnyder website is deadly serious. When compared to comical images of Moore, the effect is extremely powerful.

But perhaps the most telling comparison is between Moore’s campaign to have the governor arrested and his campaign to save the nation in his new film. Presented at times as a satirical farce, “Where to Invade Next” compares the humane treatment of citizens in other nations against examples of inhumane treatment here in the United States.

Reminding viewers that our military has failed to win wars since World War II, the film has Moore set off on a quest to “invade” other countries and come back with ideas that will strengthen us. Moore learns how the French are committed to feeding their school kids healthy and delicious lunches and how teachers in Finland did away with homework and raised their school system to No. 1 in the world by focusing on helping children enjoy life.

The contrast with the lead poisoned children of Flint could not be more dark and disturbing. Flint children don’t even have healthy water to drink let alone nutritious school lunches and top-ranked schools. Moore’s film suggests that it’s time for U.S. residents to fight to get their nation back from corporations, from corrupt politicians, and from a culture of racism, bigotry and greed.

When Moore filmed “Where to Invade Next” the idea was to ironically suggest that he should take over our country. His goal was to offer U.S. viewers a chance to imagine what can be possible when a culture truly cares about its people. Little did he know that, shortly after the film’s premiere, what was meant as a political rallying cry for the nation would echo such an urgent story of life or death in his own hometown.

Shares