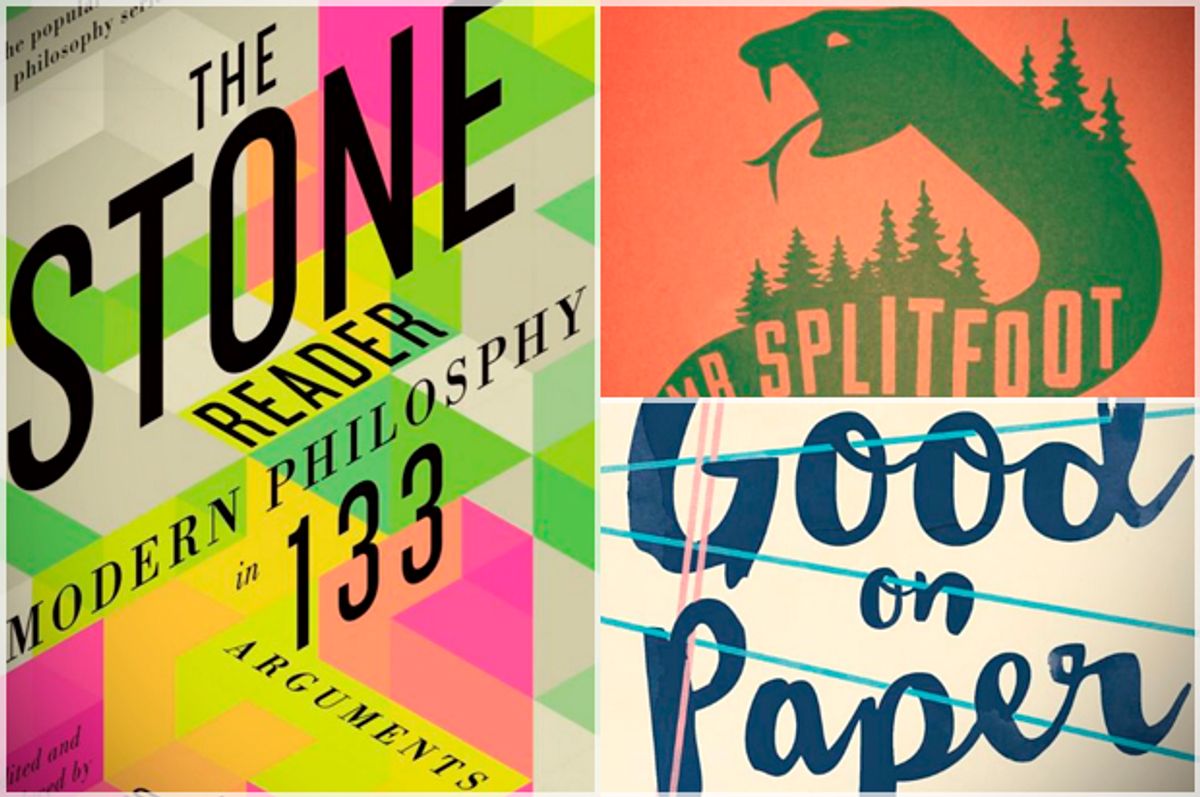

For January, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to five authors with new books: Rachel Cantor (“Good on Paper,” Jan. 26), Peter Catapano (co-editor of “The Stone Reader: Modern Philosophy in 133 Arguments”), Samantha Hunt (“Mr. Splitfoot,” out now), Maria Konnikova (“The Confidence Game: Why We Fall For It . . . Every Time,” Jan. 12), and Mira Ptacin (“Poor Your Soul,” Jan. 12).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

CANTOR: The traitorous translator, mothers, fathers, daughters, Zeno’s arrow, NY before 9/11, language-love, innocence in all its forms, bumpy narratives, forgiveness, friendship and how we love, being the flame.

CATAPANO: Everything. Or many things. Ethics, consciousness, politics. Does the human condition sound pompous? It’s sort of true. And dismantling views we have because of received wisdom or other nefarious factors, like intellectual laziness.

HUNT: “Mr. Splitfoot” is about the ways we get haunted: dead people, mothers, religion, lost things, scary stories. It is also about taking a really long walk.

KONNIKOVA: The power of belief—and our deep, hardwired, even, need for meaning and connection. It's about how stories can be used for good or ill, how central they are to our lives, and how, in the end, they make us human.

PTACIN: Survival and preservation, immigration and one’s relationship with place, grief and recovery, the layover between youth and adulthood, sexuality, reproductive choices, and the uterus and the American Dream.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

KONNIKOVA: "House of Games." Growing up in Soviet Russia. Bernie Madoff. Lance Armstrong. Noir. Manhattan blocks that sport multiple psychic shops within a 10-second radius. The frustration, rage, and tears of fraud victims. The blithe, unrepentant gleefulness of their tormentors.

HUNT: The con artistry of people who talk to the dead, maps, geology, the audio walks of Janet Cardiff, the voice (and loss of the voice) of singer Linda Thompson.

CATAPANO: Socrates, on a technicality, because he wasn’t really an author. Music. Song lyrics, band names. (I am a drummer.) Street preachers. Hyde Park, the Agora. A compulsion to propagate the art of the essay, and an adolescent need to surprise, agitate, and charm people I’ve never met while they are having their morning coffee.

PTACIN: Reproduction and reproductive choices, one’s coming of age, dating in New York City, Catholic guilt, our current healthcare system, taboos surrounding sex, the GOP, Binders full of women, jazz music, and a strong Polish mother.

CANTOR: Growing up near Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere, Paolo and Francesca, romantic difficulty, learning the "Song of Songs" with Zalman Schachter Shalomi, z’l, the Upper West Side post-college, youthful hours translating Paul Celan for my eyes only.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

PTACIN: New York City, online dating, graduate school, accidental pregnancy, loss of pregnancy, marriage, PTSD, training for a marathon, dog adoption, moving to an island in Maine, another pregnancy, birth of son.

KONNIKOVA: Birth. New nieces and nephews, a constant joy. Death. Sudden, unexpected, destabilizing loss. Too much work. Too little sleep. Dreams of oceans and beaches and hours of time to lounge and read and think. Absence of oceans and beaches from waking life. Moments of quiet happiness and marvel.

CANTOR: One-fifth of my life’s journey, everything else on hold, endless rejection (also: doubt, despair), residencies, short story prequels, innumerable start-overs, penny-pinching, scraping by, silent retreats, cigarettes, karaoke, NYC couches, literary lifesavers.

HUNT: Pregnant with twins, raising three kids under the age of three, leaving Brooklyn for a small town upstate.

CATAPANO: Always. Thinking. How. Words. Work. Pencils. Jersey Shore. Taylor Swift. Tomato sandwiches. Red clam sauce. Ice cream. Posterity.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

HUNT: Symbolic, surreal, post-apocalyptic (???!), “Cormac McCarthy-ish.” While I admire Mr. McCarthy’s writing, no thank you.

KONNIKOVA: Superficial. Repetitious. Familiar.

CATAPANO: The only word I hate is “indeed” (except when used by a member of Monty Python). No one has used it in describing my writing. But I think I may have accidentally used it myself in the introduction.

CANTOR: Confusing. A fast read. Academic whimsy. Obscure. Overstuffed with ideas. Postmodern.

PTACIN: One reviewer called my husband “long-suffering” and me “cranky.” One reviewer said they prefer to start stories in the beginning and end in the ending. But I actually loved that critique.

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

CATAPANO: Surfer. Gamelan master.

PTACIN: Musician. Cheesemaker. Botanist. Veterinarian. I’d like to own an animal sanctuary someday.

HUNT: House builder, singing superstar, geologist, bakery owner.

CANTOR: Irrespective of talent, meaning I could be as good as I can imagine being? I’d sing! I’d be a jazz soprano, an early music alto, and occasionally I’d sing bluegrass harmony in any key you like. Nothing would stop me from singing on the street. I’d make Obama weep and wear all the best hats.

KONNIKOVA: A female 007.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

PTACIN: I’ve figured out how to see the matrix of structure. I’m pretty good at creating complex story structures, but I also know when to keep it simple. I could always improve my vocabulary. I could also learn the technical terms of the tools of writing, but...nah.

KONNIKOVA: My strong point, I think, is synthesizing research and making complex facts seem elementary and intuitive—in essence, condensing hundreds of pages of reading and research into a few simple sentences. I'd like to improve my ability to structure stories that can truly carry you through an entire book, without any loss of narrative tension. I wasn't allowed to name authors before, but let me name some here: I'd like to do what seems to come so easily to Michael Lewis or Erik Larson—craft narratives that go deeply into a non-fiction subject, but manage to read like riveting fiction.

HUNT: I enjoy language and spend time trying to make beautiful sentences. I am far less agile at plotting. It takes me a long time to know what is happening in any book I’m writing.

CANTOR: I think I’m good at dialogue, synthesizing lots of ideas and threads into a (I hope) coherent narrative, being funny, and imagining what’s not there. I’d love to be better at observing and describing what is. I’d like to know how to make my reader cry.

CATAPANO: When I read, I hear voices, rhythms. When I write, I speak in my head, and when I edit I feel I can get the voice of the writer faithfully enough, and stay true to it when making changes. I’d like to be better at concentrating, a better time manager, and a better skateboarder.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

CATAPANO: I don’t. You have to start with the assumption that no one cares, because it’s true, then make them care, through means of skill, insight, instigation, and persistence.

CANTOR: I know my mother’s interested, and my father, and my (numerous) brothers and sisters, and my boyfriend and some of my friends; for me, that’s enough: I’m happy when they kvell. I also know books have the potential to move and delight; I know this because I am often moved and delighted by what I read. So I hope to reach the moveable and delightable. That feels ambitious but not particularly hubristic.

PTACIN: I don't think I have to contend with hubris at all, even though I am a very, very smart person. On the other hand, if I'm so smart, why aren't I rich? That's a question I contend with a lot more.

KONNIKOVA: I'm still amazed every time anyone other than my immediate family says they've read and enjoyed something I've written. I'm not trying for fake humility here. I really do have to try to convince myself repeatedly that I have something worthwhile to say.

HUNT: I don’t ever think anyone beside my family (granted, it is a large family) will read my books so I don’t really encounter that problem.

Shares