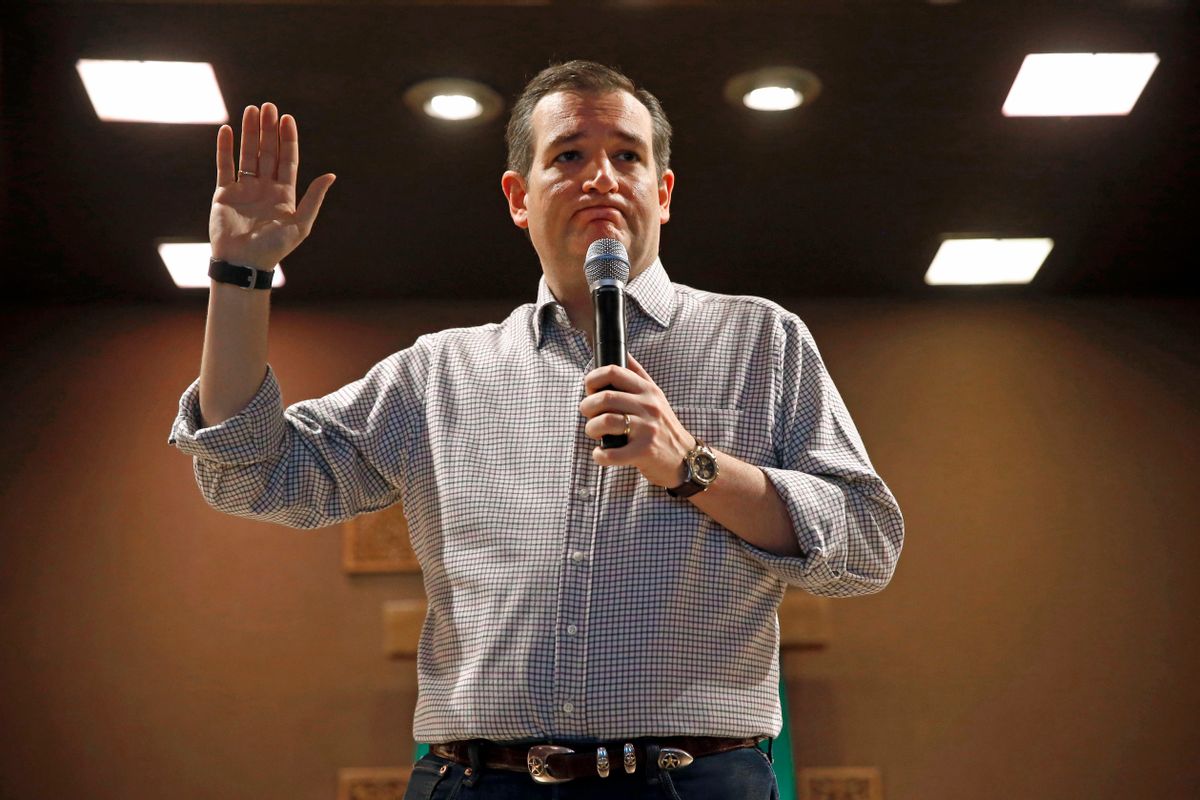

The uproar Donald Trump caused by stirring the pot over the eligibility of Canadian-born Ted Cruz to serve as president awakened constitutional scholars. With or without biases, a good many of them have suggested that the historical record is not on Cruz’s side. By the nature of the news cycle, one thing or another will remove this new “birther” controversy from public view; it really shouldn’t go away, however, because the issues are broader than what the commentators are addressing.

Most who have studied the question at hand focus on the “original intent” of the founding generation. The most obvious problem concerns the meaning of “natural born” as written into the Constitution, and whether Cruz’s birth in Calgary disqualifies him. But two equally salient issues have been ignored. The first is that Cruz’s claim to natural-born status is based on his mother, because his Cuban-born father did become a Canadian citizen, and was only naturalized as an American citizen in 2005. Rafael Cruz came to the United States on a student visa, and kept his Cuban citizenship until he became a Canadian citizen. It is a historical fact (and a fact of law) that mothers did not possess the same right fathers did to grant their children American citizenship when the child was born outside of the United States. This is important.

The second underlying point commentators have ignored is the deeply troubling legacy of American democracy in allowing discrimination against a sizeable number of its “natural born” citizens––obviously we’re talking here about African-Americans––while making exceptions for a few whose claim is tenuous at best.

Many students of the Constitution misunderstand why “natural born” was added to the qualification for president. The legal historian Mary Brigid McManamon recently argued in the Washington Post that the term was derived from the common law notion of being born on the “soil” of the national domain. In the 1780s, “natural born” was a measure of political affection and political loyalty, which only proceeded from a person’s giving tangible evidence of having a genuine commitment to the “soil” and manners of the nation. The phrase, therefore, involved potent sentiment.

To say that “natural born citizen” is settled law is nothing more than a rhetorical ploy. It is not surprising that legal experts Neal Katyal and Paul Clement of Georgetown took to the Harvard Law Review to argue the opposite side from Harvard’s Lawrence Tribe on Cruz’s eligibility, because the same argument has haunted past scholars. In 1988, long before the Cruz question arose, Jill Pryor wrote in the Yale Law Journal (scrupulously documented) that the question of whether a person born abroad of one American and one alien parent “qualifies as natural born” remains unresolved. The meaning of citizenship has changed over the course of American history, and yet the Supreme Court has never made a specific ruling on this part of Article II of the Constitution. Most recently, in Salon, Harvard legal scholar Einer Elhauge makes a strong case against Cruz’s eligibility; but even he does not go far enough to clarify the questionable status of a mother’s right to pass on her citizenship to her children.

As groups within the United States have been alternately granted rights and divested of rights, there has never been a uniform definition of what constitutes a natural born citizen. In June 1775, the Continental Congress passed a resolution declaring that all living within the United Colonies, under the protection of its laws, were now members of a new government. Here, the measure of civic belonging was residence, and the purpose of the law was to force a divided population to lean to the rebellious Patriots. Because the act was considered an insufficient test, George Washington, commander of Continental forces, and other military and state officials, demanded that Americans swear allegiance by taking a loyalty oath. By war’s end, Americans who remained loyal to Great Britain (perhaps 20 percent of the population) were prosecuted as traitors; some were executed, and many had their property confiscated. Citizenship, then, was both voluntary and coerced.

Beyond this legacy, “natural born” reflected another important feature we forget: Patriots had to construct a new identity to justify revolution, to define themselves as other than British. In 1774, Thomas Jefferson published "Summary View of the Rights of British America," in which he argued that Americans had fought and spilled their own blood to secure the American continent. They were people of a distinct lineage––which he repeated in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence. He insisted that repeated wrongs inflicted by the British government offered ample evidence that America’s colonists were no longer brethren of the same blood separated by an ocean. Now they owed their identity to an inbred allegiance on blood-soaked soil.

Thus, when delegates to the Constitutional Convention gathered in 1787, they did not qualify “natural born citizen” merely to protect the presidency from foreign intrigue. Clearly, they felt that “natural born” meant being born within the boundaries of states but also possessing a deep love of soil and manners unique to the United States. This is why the framers made an allowance for anyone naturalized at the time of the Constitution’s drafting. A naturalized foreigner acquired full citizenship and could stand for president based on having supported the Revolution––why Caribbean-born Alexander Hamilton could have run. He had displayed ardor and allegiance during the war. “Natural born” was added because it insured an unwavering identification, presumably ingrained from birth.

But allegiance is an unstable concept. In the 1790s, George Washington’s Federalist Party wanted to amend the Constitution. Several New England states called for adding the “natural born” restriction to the office of vice president. A concerned citizen wrote in a newspaper in 1798: “Would to heaven, that the same check was provided by the constitution, in every department of government, as is in the election of President; which is, that none but natural born citizens are eligible to be elected.”

Fears about the French Revolution and “Jacobin” journalists (foreign-born) who spread dangerous ideas led Congress to change naturalization laws, extending the period of residency from two to five, and then to 14 years. In the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, the president suddenly obtained authority to deport any alien who criticized the president or the government. When a modified Naturalization Act passed in 1802, and returned the residency requirement to five years, a foreign-born resident still had to declare his intention to become a citizen three years before he officially applied. He had to display his allegiance, his affections; he had to find patrons, witnesses who swore to his worthiness. So, if we are talking about “original intent,” let us not guess at, but factually encounter, the founders’ world.

It is just as obvious that women, historically, have not been treated as co-equal citizens. In the 1805 Massachusetts Supreme Court case of Martin v. Commonwealth, the Court declared that the wife of a Loyalist had no civic identity whatsoever. She had no power to own property, to choose an allegiance, to make meaningful political decisions about herself or her children. New Jersey was the only state that allowed property-owning women the right to vote (from 1776 to 1807), a right that was taken away.

Here’s why that precedent matters. In 1855, Congress passed another important law, declaring that any foreign-born woman who married a U.S. citizen automatically became a naturalized citizen, and that any children born outside the country to a male citizen was a U.S. citizen. More critically, in the Expatriation Act of 1907, women who were U.S. citizens and married foreigners, by consequence of having done so, lost their right to citizenship! The Cable Act of 1922 again allowed for American women who married “aliens ineligible to citizenship” to lose their citizenship. This punitive law was not repealed until 1934. As late as 1961, the Supreme Court ruled that the 1802 Naturalization Act only made a child born abroad a citizen if the father was a citizen. So the idea that a mother had the same right as a father did to grant citizenship to her child is simply not true. The citizenship of Ted Cruz’s Delaware-born mother means less than the candidate wants to believe.

Women did not acquire the vote until 1919. They were routinely compared to children, lacking the maturity and autonomy to be independent citizens. The 14th Amendment (1868) did grant citizenship to all residents born within the United States; but the 15th Amendment explicitly excluded women from the right to vote by adding the word “male.” Women did not have equal custodial rights over their own children until the 20th century. By law, a wife was expected to set up residency with her husband, and to follow him. Women were not constitutionally guaranteed the equal right to serve on juries in all fifty states until 1975.

At the time of the Constitution, then, what mattered was whether the father was a citizen. The New York jurist Chancellor James Kent was the foremost authority of his day: in his 1826 "Commentaries on American Law," he argued that both the father and mother had to be citizens for the child to be natural born.

The historian James Kettner, a modern expert on citizenship, is now deceased, so he can’t be charged with political bias in his statement that the Constitution spoke unequivocally: Persons naturalized before the Constitution’s ratification were eligible for office on the same terms as native Americans; but “persons adopted [into the country] thereafter were permanently barred from the presidency––the only explicit constitutional limitation on their potential rights.” That the framers made this their sole exclusion indicates that it was an important provision.

American citizenship, in general, albeit inconsistently, relied on two basic rules: one was jus joli, that citizenship came from being born within the territorial boundaries of the nation or a state; the other was jus sanguinis, of blood, as passed from parent to child. In our history, these rules have been withheld from certain classes: African Americans were not guaranteed civic status under jus joli until 1868; mothers were explicitly denied the right to grant their children citizenship under jus sanguinis from 1855 until 1940.

What’s more, American law did not endorse dual citizenship until recently. This is why the 1855 statute cited above automatically made into U.S. citizens foreign-born women who married U.S. citizens––citizenship earned through the fact of marriage. Yet foreign-born men who married U.S.-born women were not, on that basis, granted citizenship. Men had to be naturalized, prove their residency, and over time demonstrate eligibility for citizenship.

This is the history. This is the dilemma the lawyer and presidential hopeful Rafael “Ted” Cruz faces. The American founders clearly intended “natural born” to mean born within the United States; and they only granted the exception to citizens naturalized at the time of the Constitution’s framing, because these men could be presumed to have proven their loyalty by consciously choosing to side with the Patriot cause in 1775-1783.

The wording of Article II on presidential qualifications explicitly divides the population into two eligible groups: those natural born and those naturalized before 1787. Only members of the Revolutionary generation, risking all (their lives and property) were eligible for the highest executive office. Women were looked upon differently: under the law, a woman born in the United States could be executed for treason; but citizenship rights were denied insofar as her attachment to the Union was compromised by her marital status if the loyalty of her husband was in some way suspect. Needless to say, no woman of that era held elective office.

To be sure, the current debate over Sen. Cruz is at once political and constitutional. But in light of the above, the fact that it is his mother, not his father, who is American-born strikes an inescapable historical chord. Nor should it be omitted that the “birthers” who attacked President Obama’s eligibility were keen on believing that his mother’s nationality carried less weight than his father’s African blood and Kenyan birth.

John McCain’s standing rested on a different set of facts. He was born on a military base outside the United States, and both of his parents were U.S. citizens. There was little argument. The real source of the current angst dates to 2004, with the abortive effort to eliminate the “natural born” requirement so that the Austrian native Arnold Schwarzenegger could run for president. At the time, prominent legal scholars supported such a reform, and many pointed out that a change in the law would allow foreign-born children adopted by American citizens to be eligible too.

Another related issue is the anti-Mexican campaign, revived in the 1990s, and waged against female immigrants and their “anchor babies,” seemingly undeserving of birthright citizenship. Once again, women’s status and women’s allegiance was the focus of attack. During the current campaign, Donald Trump unabashedly declared that he supported amending the Fourteenth Amendment along these lines. So, the overlapping debates show how arbitrary such distinctions are.

Why should a natural born citizen with a foreign (Mexican-born) mother be barred from birthright citizenship, while Ted Cruz’s claim to natural born citizenship (and eligibility for the presidency) is through his natural born mother? And why should a foreign-born baby adopted and raised by American citizens be seen as less of a loyal citizen or potential president than a Ted Cruz?

No matter what legal pundits or scholars with a political agenda say, the law is not settled. The question of national inheritance persists. What is settled among historians, however, is that the founders did restrict the presidency to natural born citizens alone. In their parlance, American identity was rooted in an allegiance to the soil that came from a prolonged residency and manners instilled from birth; if born outside the United States, status and eligibility came from a patrilineal inheritance passed from a loyal father to his legitimate child. Even under current law, the right of a child to inherit citizenship from one parent cannot be passed onto his or her descendants. It is a right contingent on the child returning and claiming that right by resettling in the U.S.

Ted Cruz’s status is further complicated by his dual citizenship. He acquired Canadian citizenship at birth, and only recently renounced it. Can a person be “natural born” in two nations? Which “natural born” identity trumps the other? Cruz’s claim to being a “natural born” U.S. citizen is a legal fiction, of course, because his real identity as a child was a mixture of a Cuban-born naturalized Canadian father and an American mother. He remained a natural born Canadian even after he moved to the United States, and he only substantiated his claim to American status when he took legal steps to declare his citizenship--for example, when he acquired a passport and voted. He became an American citizen retroactively; his actions did not erase the equally powerful presumptive claim of his Canadian nationality. If Cruz’s parents had remained in Canada, and his mother had become a Canadian citizen, Ted Cruz no doubt would have become a Canadian citizen.

All of this matters right now because the Republican presidential candidates seem so intent on opening the door to some immigrants and excluding others. It is plain to all that the path to citizenship is neither equal nor fair. The path to the presidency is neither equal nor fair either. Both paths are political.

Cruz’s campaign in the heartland centers on the claim of being “one of us.” That is indeed the issue. A sizable portion of Americans no longer care whether the president is professionally qualified, has adequate leadership experience, foreign policy credentials, or understands the laws of the land. Amid candidates’ bombast and the day-to-day efforts to make news “by any means necessary,” we find one front-runner who gained national attention on the basis of a canned reality TV show. Cruz made his name by grandstanding in Congress in an attempt to shut down the federal government, a move that cost taxpayers millions. He made headlines with a childish, self-serving filibuster, unproductively reading aloud from Dr. Seuss. Forget “New York values.” What are his values? To whom does he feel loyalty?

In 1776, Pennsylvanians were asked to take an oath to “vote only for such persons as I do esteem of fidelity and knowledge, worthy and capable of executing the trust reposed on them.” Fidelity. Serving honorably. Maybe that’s the lesson from the founders we should take at this moment in our history. Nothing is of more gravity than taking the oath of office as President of the United States. Campaigning for president should be as serious.

It is tempting to find on the side of the partisans, who would prefer to let the Constitution eliminate Ted Cruz from contention altogether. But the truth is, there is no settled law, one way or the other.

Shares