E.J. Dionne’s work has had a consistent theme over three decades: We deserve better than the un-serious politics we get. In his masterful 1991 book “Why Americans Hate Politics,” Dionne argued that “there are more ideas that unite us than divide us, but politics doesn’t reflect that.” We hated politics then, he explained, because it had become a selection of false choices, presented by “conservatives who failed to represent their interests and liberals (who) have lost touch with their values.”

Twenty-five years later, our politics remains divided, dysfunctional and no more serious. The Republican primary field dominated by an authoritarian carnival barker and a senator so unyielding that even the deeply stubborn conservative men who run the chamber find him too intransigent. And Dionne has a crucial new book that explains this dangerous moment with passion, clarity and erudition.

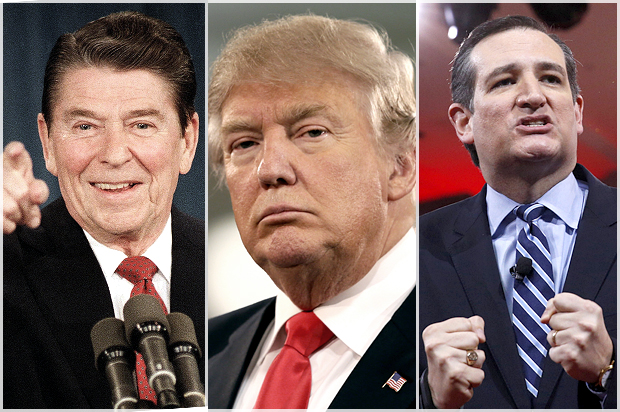

In “Why The Right Went Wrong: Conservatism From Goldwater to the Tea Party and Beyond,” Dionne argues that since 1964, in election after election, Republicans have made promises that they are either unwilling or unable to deliver upon. The result: An endless cycle of disillusion and betrayal amongst the conservative faithful that has driven the party ever-rightward — and into an irresponsible permanent party of extremism and obstruction.

Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, two George Bushes — none of them could make real the rhetoric conservatives used to rally the like-minded. “In response,” Dionne writes, “movement conservatives advanced an ever purer ideology, certain that doing so would eventually bring them the triumphs that had eluded them.” It not only hasn’t happened, but Republicans have lost the popular vote in five of the last six presidential elections. Gerrymandering and the inherent red-state bias of the Senate has created a near-eternal divided government, with a Republican Party that’s “committed, on principle, to preventing its adversaries from governing successfully.”

If we hate politics in 2016, it’s because Republicans have embraced a “reactionary radicalism” that’s taken the entire democracy hostage. Conservatives either heal themselves, or render the country ungovernable and unsafe at a crucial juncture. Dionne’s an earnest and erudite progressive, so this diagnosis may not seem surprising. What makes this book so compelling and necessary is not only his historical analysis, but the depth of the research and reporting and the clarity with which he lays out this most complicated and thorny dilemma of our time. Pair it with Jane Mayer’s “Dark Money,” the month’s other must-political-read, and you’ll understand exactly how we arrived in this broken moment.

We talked to Dionne, a Washington Post columnist and NPR regular, on Friday afternoon, as he traveled Iowa in advance of this evening’s caucus. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

You’re calling from Iowa, and the caucuses are Monday, so let’s start there. Your book traces conservative discontent from Barry Goldwater and 1964 forward, but it also seems to me that the Republicans created this uncontrollable Trump Frankenstein themselves with their big wins in 2010. They gerrymandered a decade-long permanent majority in the House, built districts where the only challenge could come further from the right, and created a sense within a restless base that they were about to have big victories. Those victories would never come with a Democrat in the White House. But the base looks at this and believes the party just isn’t fighting hard enough. So you get Trump and Cruz – and a plan that looked brilliant after 2010 spirals out of control…

I totally agree. The line that has been coming back to me a lot lately is one of my favorite John F. Kennedy lines from his inaugural address, where he said, “In the past, those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.”

The Republicans did a number of things to win that created the circumstance that leads to Iowa, where the top two candidates are both candidates that large parts of the party leadership wish weren’t there. I think problem one was feeding the Tea Party and a particularly radical view of the United States and of Obama — that somehow President Obama was a Muslim, a socialist, an extremist who was going to transform the country into something Americans wouldn’t recognize. That was not true: he is not Muslim, even though it shouldn’t matter if he were. He is not a socialist, as Bernie Sanders, by contrast, is showing us. He is not someone who wants to create a strange new America. The stock market’s doing great, the economy is picking up. He probably hasn’t done enough, and I think he thinks this himself, about income inequality.

His health-care plan that Republicans are so determined to repeal and replace came out of the Heritage Foundation and, as you point out, it was probably further to the right than what Hillary and Bill tried to do in 1994.

Not only that, it was further to the right than what Nixon proposed back in 1971. So they’ve created this monster of Obama and of this radical departure, which a lot of their own people believed. When they said all these things, but couldn’t deliver, they created this very angry constituency. So that’s one problem that they helped create. They kept promising and promising that they would actually do something about this “socialist onslaught” when they couldn’t really do it.

I do think some of these promises go all the way back to Goldwater. The first line of the book is, “The history of contemporary American conservatism is a story of disappointment and betrayal.” Going right back to the beginning, one of the core promises of modern conservatism, that they could create a smaller government, was simply impossible. Nixon didn’t do it; in fact, he actually grew government. Reagan didn’t do it, Bush didn’t do it, Bush II didn’t do it. It’s not a conspiracy, it’s because most Americans want a lot from government, including Tea Party folks who are at or over the age of 65 who will criticize all kinds of programs but also insist, “Don’t take away my Medicare or Social Security.”

Conservative president after conservative president has not delivered on that promise. If Nixon, Reagan and two Bushes don’t actually deliver smaller government, maybe conservatism is actually about using the government in the service of different and well-heeled interests.

That is certainly partially true, because obviously conservatism had no problems using government to impose a certain vision of what America should and shouldn’t be like. Obviously abortion is a good example of that, an issue that I admit is very complicated. I respect right-to-lifers, but it is an aggressive use of government.

You have all these guys — not all of them, Rand Paul is a true small government libertarian — saying we want a smaller government but we want to beef up the military. They say we want a smaller government, but by the way, we won’t cut Social Security or Medicare for anybody who now gets it or is about to. Partly because their own constituency is on the old side, which is a long-term problem that we can talk about.

So, it’s an empty promise. One of the reasons I lift up Eisenhower as the alternative to Goldwater at the time, and representing in his core beliefs something like what conservatism needs now, is that Eisenhower was certainly a budget balancer. He was certainly prudent, he was certainly pro-business, he was all these things conservatives like — but he did not pretend that you could roll back the New Deal. He did not pretend that Americans wanted nothing from government. He was willing to use government where he thought it was appropriate. He created the interstate highway system; he created the student loan program, which helped me go to college. Eisenhower was conservatism as prudence and trying broadly to preserve the American way of life, while accepting that certain things change with the times because the problems change. I still think, in the end, conservatism is going to have to go back – or forward, in a way – to being about that, and not about a series of ideological slogans that include promises they can’t keep.

Why do they keep making these promises? They understand how the system of checks and balances work; they understand what a presidential veto is. Did they ever think they would deliver? After every election that Republicans have lost for decades, the lesson learned was, “Well, that time we weren’t conservative enough, so next time we’ll move further to the right.” And here they are.

Partly it’s aspirational. If they wanted to make a case that they are somewhat less likely to regulate the market than liberals or progressives are, that’s a plausible case. Indeed, they have tried and succeeded in some cases — in some cases Bill Clinton signed the bills in deregulating the financial market and transportation, which Ted Kennedy was involved in. There is a sense in which there is a truth here that they’re espousing, but where their claim on truth breaks down is when it comes to the core functions of government. The tend to define this problem as – I talk about this problem in relation to Mitt Romney’s announcement speech – if government reaches a certain percentage of GDP, if it goes over that then suddenly we’ve lost our freedom, and that’s pretty much what Mitt Romney said in that speech. And that’s just not true; that’s never been true.

Just to go back to the original question about Trump: When Republicans decided in the House not to take up the immigration bill that passed the Senate with considerable Republican support, including for a while Marco Rubio, they started putting out all sorts of rhetoric about how people were flowing across our southern border illegally. They were saying this at a moment when net immigration from Mexico was below zero — because of the recession, people were going back. But if everything was as bad as they said it was, why shouldn’t people vote for Trump instead of the party establishment? So I think there has been this sloganeering to appeal to the angriest parts of the right to keep it mobilized, when the party leadership had no real intention of acting on what the full implications of that rhetoric were.

That’s a really dangerous game.

Yeah, and that’s where Donald Trump is picking up on them. “If things are that bad, let’s throw everybody out and send them back to Mexico and build a wall,” he says. Now of course that’s an absurd policy and it’s inhumane, but it follows logically from rhetoric that you’ve been hearing on that side.

I think the other thing that really strikes me as the election season begins is that the older party leadership – I’m skeptical of the word establishment – the older party leadership is desperate to stop Trump and Cruz, but when they look around, the votes to stop them aren’t in the Republican party anymore. Because by pursuing this turn to the right – a lot of it rhetorical, some of it real – they have driven out all of the moderate voters. People who were good moderate Republicans, or even moderate conservatives, who voted for George H.W. Bush back in ’88, they don’t vote in Republican primaries anymore. They started shifting to being independents or even Democrats during the Clinton years, and that’s continued. When they need voters to save them, the voters are gone. I think that’s a central dynamic of what’s happening in these primaries right now.

That’s especially true in the Iowa caucuses, which tend to draw particularly ideological voters because it takes a bigger commitment to go to a caucus. But if you look up in New Hampshire, the only way Trump might be stopped up there is by independent voters who are no longer Republican. The leadership of the party doesn’t have the troops anymore inside the party to do what they need to do in primaries, for the most part.

The Fox News poll from New Hampshire a week ago, it took the support of Christie, Bush, Rubio and Kasich together to approach Trump’s number. The troops they do have remain divided – and, of course, there’s no telling that, even if the field thinned, if some of their supporters would move to Trump or Cruz as a second choice.

That’s another point I make in the book which I think is important in looking forward to these primaries. There are a lot of smart Republican strategists who make the point, fairly, that in the last two elections the more moderate conservative, compared to their opponents, prevailed: John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012. But if you look carefully at both contests, the reason both McCain and Romney prevailed is that it was the conservatives splitting up their side of the vote. In 2012, Gingrich and Santorum, combined, were ahead of Romney in many states. And in 2008, McCain was very lucky because his more conservative adversaries kept knocking each other off, so that Huckabee beat Romney in Iowa, then Fred Thompson took enough votes away from Huckabee to allow McCain to win South Carolina. McCain won these early primaries with no more than a third of the vote.

So this dynamic in the Republican Party has now been there for awhile, that the staunch conservatives dominate the primaries. In the past, it was the conservatives that split the vote. Now there are enough of them to go around that Cruz and Trump can split the vote and you’ve got these four serious candidates on the other side who can’t even unite their now minority share of the party. The long purge of moderate and once-upon-a-time liberal Republicans has taken its toll and led us to this.

Why do you think Obama misread the nature of this opposition for so long? It seems like he needed to see it for six years to believe that it was true — and that it was going to stay that way, and his own powers of reason and civility wouldn’t ever bring cooler heads around.

I think Obama did what he did partly out of principle and a sense of who he is and partly, oddly perhaps, for certain political reasons. In terms of calculation, he is a reasonable person who likes to dialogue with Republicans. In the book I talk about how he became president of the Harvard Law Review because conservatives on the Law Review thought he was the more open-minded liberal. I think from that time forward, he thought he could persuade conservatives. I’ve always had the impression that Obama probably enjoys arguing with smart conservatives more than he enjoys arguing with anyone else.

So that’s partly character-ological. This is in some ways unfair, but [I think he thought], “If I could do it at the Harvard Law Review, if I could get along with these Republicans in the senate in Illinois, I can do it in Washington. I won an election promising to get rid of these divisions between red and blue America.”

And then he gets zero votes on the stimulus in February 2009. About the same cooperation on health care. The nature of the opposition seemed clear even if you’re not as smart as he is. You get his advisers to open up about this in the book.

I think he was slow to move off (looking for bipartisan cooperation) partly for political reasons. I write about this in the book and some of his own people have been candid about this. They felt that if they abandoned this too quickly voters would say, “Wait a minute, what did you campaign on?” So I think he felt a certain obligation to try to stick with it for a while. I thought it was perfectly obvious after the stimulus vote that it was going to be a problem. He got no Republicans in the House and three senators, who, by the way, forced the stimulus down in size below where it should have been given the depths of the recession. I think that was the time when he should have seen it.

There’s also a story in the book, told by David Axelrod, about tensions between Obama and Nancy Pelosi early on, where she told him, “You’ve got to stop attacking Washington abstractly. First, we are Washington now. Secondly, it’s Republicans who are getting in your way, not us.” And there was another moment when Pelosi told him in a private meeting, “Mr. President, I don’t mind you throwing us under the bus. I just object to your backing the bus up and running us over again.”

Obama’s a smart man, and I think over time he realized, “This ain’t working. These guys are not gonna move.”

He’s not only a smart man, he’s a convincing orator. Had he only tried to make the arguments of this year’s State of the Union back then…

Right, the paradox is that when he took them on directly and made his case for why a more progressive approach was more sensible than a more conservative approach, he actually did well. He won the 2012 election by pivoting to a more aggressive argument. One of the ironies I talk about in the book is if he had ever gotten that budget deal with (former Speaker) Boehner, he would have thrown away many of the issues he ended up using in the 2012 election.

So now Obama has come around to this view himself. I think it’s a little late to push back against the Republicans now, but it’s led him to try to do what he can through other means and it’s led him in speech after speech to make the larger case, because this is going to a long battle. He accepts that the battle is going to go on after he leaves office and he seems to be trying to prepare the way for that.

Well, perhaps he thought these actually were Reagan Republicans. Reagan could be flexible, he could be a dealmaker, he understood negotiations and that both sides had to come away feeling they’d gotten some of what they wanted. The Reagan mythos, however, is something completely different. There’s a different Reagan for every part of the Republican spectrum, and very few of those Reagans seem to have any connection to the man who actually governed.

One of my favorite quotes in the book is from Charles Krauthammer, my Washington Post colleague on the other side of the political spectrum, who said, “You can choose your Reagan.” A light went off in my head and I thought, “Bless you, Charles, for saying that.” Because it’s true.

Ronald Reagan was both a conservative movement leader who more ideological conservatives can turn to legitimately as the guy who helped build their movement, and who at rather moments has held rather extreme positions — if you go back to what he said in opposing Medicare, if you go back to his views on privatizing Social Security.

You do have Reagan the ideologue who did actually believe these things, but Reagan was also pragmatic in the way he governed. First of all, he know how to talk to Democrats, which is where “Reagan Democrats” came from. Secondly, in the end, he too understood that there were things the government did that voters wanted government to do. Thirdly, here you’ve got to lift up Tip O’Neill and the Democratic House. He had to govern with a Democratic House and was willing to do what it took to get things done.

And, by the way, he was willing to raise taxes several times after he cut them. One of the paradoxes is conservatives never blame that on Reagan. They blamed it all on George H.W. Bush. George H.W. Bush died for the sins that Ronald Reagan committed against conservatism. They held all of that against Bush and kind of left Reagan harmless. I have a whole list of the things that would lose him a Republican primary this year.

So where did the pragmatic, deal-making conservatives go? You make the case in this book that George W. Bush and Karl Rove might have been trying to build that modern party, that they recognized both the changing demographics of the country but also that Republicans couldn’t simply run against government forever.

Some of them are still around. I have been very critical of Bush in my column. I’m one of those people who is still upset about Florida. I try in the book to look at the Bush years and what he and Karl Rove were up to from a certain distance and say, “What is it that they saw?” On the one side, there was a certain genius there in understanding that Bill Clinton really had changed the nature of the debate in important ways. But he and Rove also understood that the Gingrich Congress was very unpopular, that people did not like a Republican Party that didn’t seem to care about poor people, and that it was very important that conservatives get on the more popular side of certain issues like a concern for public education.

“Compassionate conservatism” was the term they used in 2000.

In the early days of compassionate conservatism, before the term was widely used, Clinton seemed to be paying more attention to some of the things they were talking about than many Republicans. It’s worth noting that on the whole issue of government aid to faith-based organizations, the first faith-based center in government was established under Bill Clinton, not under George W. Bush. But the problem is that Bush, I think, abandoned his own experiment or never really put a lot of muscle behind it.

September 11 happened, and he became a different president. And the party used patriotism as a weapon against Democrats in the 2002 midterms, and then it was onto Iraq and Afghanistan.

Yes, 9/11 happened and imposed a new agenda. So some of it was not by choice, but some of it was by choice. When Rove looked at the fact that Bush did not win the popular vote in 2000, he discovered that maybe this appeal to the center doesn’t work. They didn’t mobilize the base enough, and so he turned more to a base strategy, even though he did do No Child Left Behind and they did do the prescription drug benefit.

What’s the role of race in the drift of GOP party rightward over these years, and the creation of what has become a white, largely Southern base?

Race is a very important part of my story. I always knew race was important, but working on this book made me realize race was even more important than I thought. One of the figures I admire is Ira Katznelson. His book “Fear Itself” is a truly great and somewhat revisionist view of the New Deal era. It was Ira who turned me on to how the Democratic coalition was beginning to fall apart around race going all the way back to the late 1930s, when Southern right-wing segregationist Democrats realized that as African-Americans drifted north they went to big cities and started voting Democratic because of Roosevelt. Suddenly, their former Northern allies – because Northern Democrats used to be complicit in maintaining segregation – suddenly depended, in part, on the votes of African Americans to win elections.

So you really started seeing the Democratic coalition fall apart beginning in the late ’30s and certainly moving on to 1948, when Harry Truman threw the party fully behind civil rights. When you look at the writings of the earliest conservative intellectuals and strategists, people like Bill Rusher, even Bill Buckley, it was clear that they were counting on the votes of Southern conservatives, which at the time meant Southern segregationists, to help build this new Republican coalition. Some conservatives have come to terms with that. I think some of the compassionate conservatives try to face up to that, but I think there is still a lot of reluctance on the right to face up to how much a backlash against civil rights fed.

As you’re seeing in the Trump campaign, it continues to feed the Republican coalition. I think it’s something conservatives have to come to terms with. This all predated Obama. And then obviously we’ve seen a racial element and some racist elements in the opposition to Obama. You can’t explain all of the backlash against Obama in terms of race. People who can’t stand Barack Obama also couldn’t stand Bill Clinton. So ideology is certainly a big part of this, but race is part of the way in which conservatives moved forward. I think we have to have a subtle but unblinking view of the role of race and racism in getting us to where we are today.

You make a plea to Republicans and conservatives to understand the importance of both sides in a two-party system being willing to govern and compromise and work together in good faith. Are you optimistic? To what extent should we be despairing over the state of democracy, and worry that the system itself has broken down?

This is one of the central arguments of the book. The subtitle of the introduction is, “Why reforming the country requires transforming the right.” I argue that progressives have an interest in a healthy, more moderate brand of conservatism. Partly because there is a dynamic, you might even say a dialectic, where progressives and conservatives need to push back against each other and that had both intellectual and governing utility. Those of us on the progressive side make mistakes and overreach, and it’s good for the country to have conservatives pushing back on us when we’re wrong, even when we may not think we’re wrong. Perhaps sometimes even when we’re not wrong.

Except that what we have seen over this period is the Republicans moving much farther to the right than Democrats have to the left – no matter how much certain elements in D.C. and in the media want to say “both sides do it.”

Yes, I think the idea of asymmetric polarization has to be accepted as a reality for us to move forward. The Republicans really have moved farther right than Democrats have moved left, notwithstanding Bernie Sanders’ candidacy for president and the support he’s getting. Pew did some very interesting survey work on this. If you ask the question, “Do you prefer elected officials who make compromises with people they disagree with or who stick to their positions?” Among Democrats, 59 percent prefer compromise-seekers. Among Republicans, only 36 percent did.

Which party is more ideological? If you ask Republicans themselves, people who call themselves Republicans, 67 percent of them in a 2014 Pew survey called themselves conservative. Only 34 percent of Democrats called themselves liberal.

Now, why is this a problem? If we were operating in a parliamentary system where one side would win, put through its program, and then get judged in the next election, this might not be a problem.

If you had a House that wasn’t gerrymandered, where there was any electoral accountability for extremism at all…

Or if we were operating in a system of proportional representation, where you had a really strong right-wing party but in order to govern they would have to come to terms with more moderate allies, that would also work. But we don’t have either of those systems. We have a system of separated powers.

Partly because of the gerrymander – I like to joke that the Senate is gerrymandered by the Constitution – but also because Democrats are concentrated in urban areas, so in terms of winning seats they waste a lot of votes, the odds of producing divided government for a long time are pretty high. If you have a Republican Party that is so completely dominated by a conservative, obstructionist approach, it’s going to be very hard for us to govern ourselves. As I argue, in the end, the vast majority of Americans don’t want that. The vast majority of Americans actually do like when government solves certain problems. We have to go through the most wacky sort of endless negotiation just to fund highways and mass transit. I quote former Congressman Steve LaTourette in the book, a moderate conservative Republican, who said, “I left Congress because we couldn’t even pass a transportation bill anymore.” This doesn’t make sense, and I think Republicans have to face up to the fact that it doesn’t make sense.

Is there any road back? Is there anybody who can help Republicans pull themselves back? It seems as though Republican intellectuals have as much to answer for as anybody else. Even your radio sparring partner, David Brooks, has twisted himself into a pretzel for the last eight years trying to rationalize and defend the party. It’s as if he only discovered in the last week exactly how insane things have become.

The two groups that I do pay attention to a lot that might conceivably push back over the long run are the compassionate conservatives and now the reform conservatives. The reformicons are at least willing to admit that throughout the Obama years the conservatives largely fell away from offering policy alternatives, so at least they’re doing some of that work, which is useful. But what I argue in the book is that in my view, they are still far too constrained by the makeup of the party and the intellectual conventional wisdom to go as far as I think they need to go.

I write with some respect for the reformicons as people who are at least trying to think through the problem. A lot of them are smart people. But I write with a lot of impatience as well. I think they really need to be more adventurous than they have been willing to be up to this point.

What my reformicon friends tell me is that I won’t be satisfied until they are liberals and social democrats. Maybe I would like to convert them all to social democracy, but that’s not really what I’m looking for from them. What I’m looking for is a more direct challenge to a lot of this rhetoric about government and its role. I’m looking for a stronger critique, for example, of all the stuff that was said about Obama when Obama was president that simply wasn’t true. Some of them spoke out. David Brooks, my friend, certainly spoke out regularly on that. But they really were quite reticent there. I think they are inhibiting their own programmatic imagination.

What role does Fox News and the conservative media play in keeping intellectuals on the right in line? I wonder if being on the Fox News payroll keeps some conservative thinkers in line, simply because being a contributor can be so valuable both financially and in exposure.

I do think that Fox News and what David Frum has called the “conservative entertainment complex” have become almost the arbiters of orthodoxy within the Republican Party and the conservative movement. Traditional party leaders have to some degree lost control over the party to the outside forces, in particular, conservative radio and Fox News on the one side and what Frum called “The Radical Rich” on the other side. This is a real constraint on the ability of Republicans to pull back from what I think of as very extreme opposition.

It’s January 29, 2016. No votes have been cast. But it does seem like there are a shrinking number of scenarios for the GOP. Let’s start with the premise that either Trump or Cruz wins the Republican nomination and then proceeds to lose in the general election. Would that open the door to a different conversation within the party? Could they lose with Cruz and really argue that they needed a truer conservative? Could they lose with Trump and really argue that they didn’t get a full airing for a full-throated howl around immigration and American exceptionalism?

My belief, and my hope, is that if the Republicans nominated someone like Trump, or particularly someone like Cruz, where no one on the conservative side could say, “We didn’t get the chance to try our ideas,” and he loses, that that could open the way to reform. I think it would free up some of the more moderately conservative voices who have been afraid of losing primaries to say, “We have now lost three times in a row. We have now lost the popular vote six out of seven elections. We really have to revisit this.”

Three defeats seems like a magic number. It was three defeats that led the Democrats to Bill Clinton. I have a mixed verdict on Clinton, as I very much respect him in what he achieved, in other respects I’m critical of him. Clinton himself has second thoughts about financial deregulation and over-incarceration. But it took three defeats for Democrats to say, “We’ve got to try something different.” In Britain it took three defeats for the Tories to say, “We’ve got to try something different,” and they turned to David Cameron.

It’s going to be hard to change the Republican Party, especially given its base in Congress. A lot of these Republicans in the House come from very conservative districts and pay no price for this, but the party nationally does.

And so do we all.

Yes. It would be good for the Republicans and the nation if they’d allow our government to work again.

<img src=”http://media.www.salon.com/

alt=”Why the Right Went Wrong” />