Six months after he organized the March on Washington, civil rights stalwart Bayard Rustin was in New York City preparing for an even larger protest. On Feb. 3, 1964, more than 460,000 students, predominantly black and Puerto Rican, stayed out of school to protest educational inequality and school segregation in the Big Apple. The New York City school boycott was the largest of the civil rights era, but few people know this history. The campaign for educational equality in New York and the widespread resistance to school desegregation are crucial to understanding why New York’s schools are the most segregated in the nation, why parents in Manhattan and Brooklyn are still fighting battles over school zoning and segregation, and why it is so difficult to acknowledge racism in the North.

The New York school boycott was a decade in the making. In 1954, New York City had the nation’s largest black population and, as in other Northern cities, school-zoning policies worked in concert with housing discrimination to segregate schools. In the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision, Ella Baker and Dr. Kenneth Clark, two of the most important African-American thinkers and activists in the 20th century, worked to make school segregation in New York an issue that school officials and politicians could no longer ignore. Clark argued that public awareness was the first goal of the campaign against school segregation in New York, “because we felt that the people of New York City were not aware of public school segregation as an issue which faced the city itself.”

For their part, school officials remained cautious about the legal ramifications of school segregation receiving wider attention. School Superintendent William Jansen directed his staff to use words like “separation” or “racial imbalance,” rather than “segregation,” in relation to New York’s schools. Still, pressure from civil rights advocates encouraged the school board to make modest recommendations to make zoning decisions in a way that would promote racial integration. These modest plans generated intense resistance among white parents who opposed plans to transfer small numbers of black and Puerto Rican children into predominantly white schools and feared that the school board would soon assign white children to schools in minority neighborhoods.

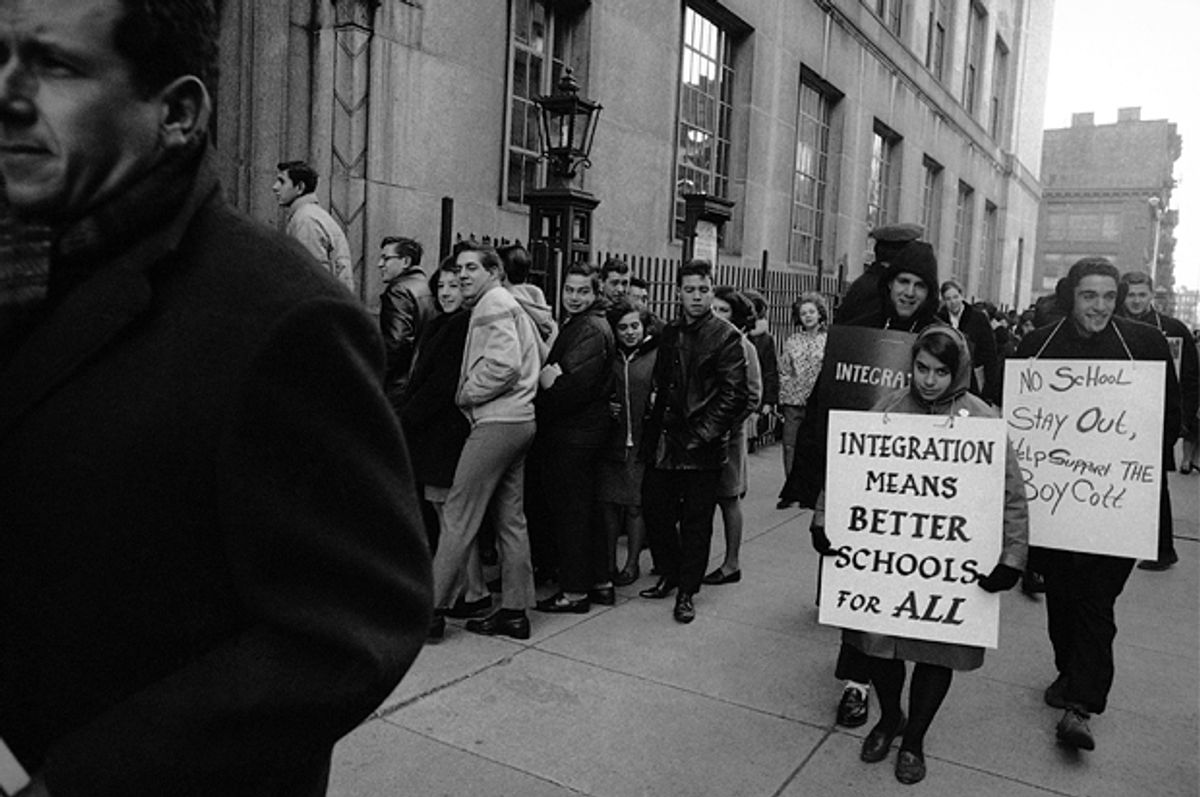

By 1964, the black community’s frustration with the glacial pace of change in the schools led to a massive school boycott. Led by Brooklyn minister Milton Galamison and organized by Bayard Rustin, the boycotters demanded that the school board implement a desegregation plan across the city. Groups of students, parents and some teachers marched in front of 300 schools and in front of the Board of Education headquarters, chanting, “Jim Crow must go,” and singing “We Shall Overcome.” Tina Lawrence, a black college student who helped organize the boycott, saw the massive protest as a challenge to New York City’s white residents. “They thought it was all right when it was happening in Jackson, Mississippi, but now it’s happening here,” she said. “The people are going to wake up.” While the boycott succeeded as a public demonstration of unity among blacks, Puerto Ricans and white liberals, these alliances began to fray shortly after the boycott, with many black and Puerto Rican community leaders and parents emphasizing community control of schools rather than school desegregation.

One of the reasons the New York school boycott does not show up in our history textbooks is that the Northern media did not cover it with the same moral urgency as they did civil rights activism in the South. The New York Times, which insisted that there was “no official segregation in the city,” criticized the boycott as “violent, illegal approach of adult-encouraged truancy” and dismissed the civil rights demands as “unreasonable and unjustified.”

Among those opposed to the boycott were Parents and Taxpayers (PAT), a coalition of white neighborhood groups who organized protest marches and a boycott against zoning changes and school desegregation in March 1964. The marchers, “15,000 white mothers” as the press dubbed them, held signs reading “Keep our children in neighborhood schools” and “I will not put my children on a bus.” These white protesters, while many fewer in number than the civil rights school boycott, commanded much more attention from politicians. Most important, they had the support of Emanuel Celler, a Democrat from Brooklyn, who helped craft the 1964 Civil Rights Act. This landmark civil rights legislation included a loophole (section 401b) that allowed school segregation to exist and expand in Northern cities like New York, Boston, Chicago and Detroit. “In my opinion the two Senators from New York are, at heart, pretty good segregationists,” Mississippi’s James O. Eastland said of his Empire State colleagues, “but the conditions in their State are different from the conditions in ours.”

Ignoring this history of school segregation and racism in the North has consequences. When parents in Manhattan and Brooklyn voice opposition to rezoning plans, they are drawing on the very same language white community groups used to oppose racial integration in the 1960s. While property values in New York City have changed dramatically over the past half-century, the language used to resist school desegregation of schools has not. Decisions regarding school zoning are always complex and politically contentious, but parents, citizens and school officials should approach these decisions by dealing honestly with the important and overlooked history of school segregation in New York City.

Matthew F. Delmont is associate professor of history at Arizona State University. He is the author of "Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and National Resistance to School Desegregation" (University of California Press, forthcoming March 2016).

Shares