From about 1970 until about 2000, American politics was largely driven by concern about the nuclear family. As established social hierarchies came under fire from the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, second-wave feminism, and others, conservative advocacy groups and their political allies demanded a return to the idealized family of the past. “Family values” became the rallying cry of a countermovement bent on holding the traditional line.

From about 1970 until about 2000, American politics was largely driven by concern about the nuclear family. As established social hierarchies came under fire from the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, second-wave feminism, and others, conservative advocacy groups and their political allies demanded a return to the idealized family of the past. “Family values” became the rallying cry of a countermovement bent on holding the traditional line.

Seth Dowland is Assistant Professor in the Department of Religion at Pacific Lutheran University. His book, Family Values and the Rise of the Christian Right, charts the influence of Christian “family values” advocacy across three decades and a variety of issues.

RD’s Eric C. Miller spoke with Dowland about the project, the politics, and the significance of family in the United States.

You introduce “family values” as the key term of the Christian Right in the late twentieth-century United States. Why was this term so influential for this group in this place and time?

Many of the political reforms enacted from the 1930s through the 1960s—particularly the expansion of the welfare state and the passage of civil rights legislation—attempted to expand equal rights to all people. Political liberals celebrated these developments, while conservatives looked around the nation at the beginning of the 1970s and saw economic stagnation, riots, sexual revolution, a decline in patriotism, and an increase in crime and drug use. Ministers and political conservatives argued that America was in decline. They believed that decline happened because of the demise of the “traditional family.”

Scholar Stephanie Coontz has shown that the concept of a traditional family—breadwinning father, stay-at-home mother, and children who enjoy a lengthy and protected childhood—is a fiction. In fact, even idealizing this version of the traditional family is a fairly recent phenomenon.

Democrats in the 1970s agreed with Republicans that they ought to promote families, but they wanted to broaden the concept of family to include single-parent families, multi-generational households, and, in some cases, gay couples. Political conservatives rejected the attempt to broaden the concept of family and placed defense of the traditional family at the center of their political agenda.

This agenda—defending and promoting family values—resonated with evangelical Christians because it spoke to two of their central convictions.

First, evangelicals believed that gender was part of the created order, that men and women were created by God to fulfill different roles. In traditional families, men provided and protected, while women bore, reared and nurtured children. Movements that viewed gender roles as the product of patriarchal social constructions—such as second-wave feminism—represented a denial of God’s good creation, which spelled out biologically appropriate roles for men and women.

Second, evangelicals believed that God designed institutions like the family and the church to run under certain authority structures. While evangelicals voiced support for equal rights, they wanted to retain the authority structures that kept human sinfulness in check. Traditional families exemplified those godly authority structures: Husbands led their wives, and parents had authority over children. Promoting family values gave evangelicals a way to uphold their beliefs about gender and authority in the broader culture.

If gender played an overt role in the rise of the Christian Right, class and race were implicit as well. The single breadwinner model of the family presumed middle-class stability, and the movement as a whole was almost entirely white. So is it fair to say that “family values” merged a diversity of issues that mattered specifically to conservative, middle-class, white, evangelical Christians?

That’s exactly right. While I talk mostly about gender, certain assumptions about race and class were part of pro-family politics. Christian schools are a perfect example of this.

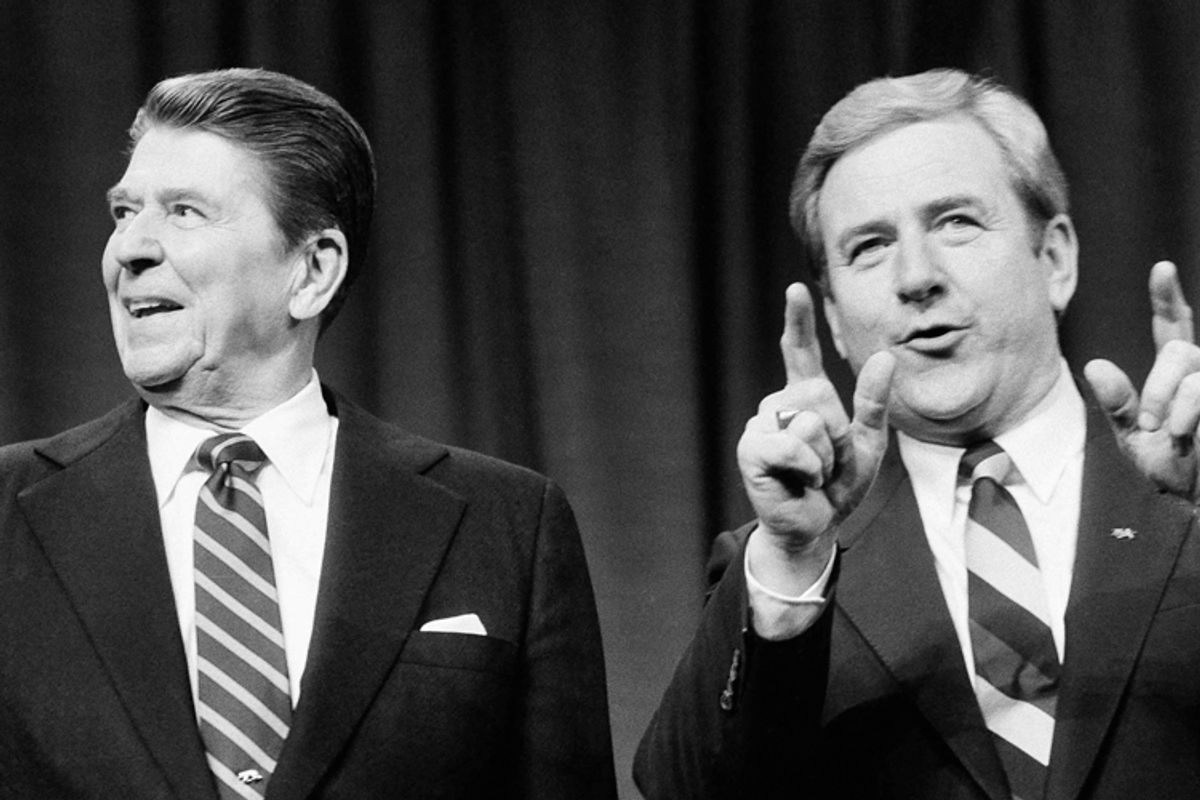

During the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, the number of Christian schools opened by conservative evangelical Christians skyrocketed. By the early 1980s, evangelical ministers like Jerry Falwell were claiming that evangelicals opened three new Christian schools every day, ostensibly because public schools had become anti-Christian. Yet this surge in Christian school growth coincided with public school desegregation. The student bodies in most of these Christian schools were overwhelmingly or entirely white.

Even so, viewing these schools simply as “segregation academies” obscures both diversity within the Christian school movement and the ways that segregationist schools changed over time. Falwell’s own K-12 school, Lynchburg (later Liberty) Christian Academy is a good example. Launched in 1967—the same year Lynchburg public schools desegregated—LCA was all-white for two years. But as desegregation became normalized in Lynchburg public schools (which had a small proportion of African-American students relative to other southern locales), LCA would need other rationales to sustain enrollment.

The school found a winning strategy in promoting family values. LCA portrayed its mission as supporting Christian families and promised to shape young men and women who knew their place. A 1975 promotional brochure for the school advertised, “we have no hippies” and “you can tell our boys from our girls without a medical examination.”

The relative lack of explicit racial rhetoric in the family values movement would later open the door for change among some conservative evangelicals. In 1990, University of Colorado football coach Bill McCartney founded Promise Keepers, an evangelical men’s organization that became one of the most important pro-family groups of the decade. As shown in the recent ESPN film “The Gospel According to Mac,” McCartney was talking about structural racism twenty years ago. He made racial reconciliation a centerpiece of Promise Keepers’ ministry.

McCartney’s understanding of systemic injustice never prevailed among a majority of conservative white evangelicals, who insisted that racism was foremost a sin of the heart. This understanding constrained white evangelicals’ ability to forge interracial alliances in support of family values. The pro-family movement found some nonwhite allies among socially conservative minority Christians, but its normalization of white, middle-class values limited its reach.

The book’s structure does a nice job of laying out family values activism as a species of identity politics, with issues apportioned to children, mothers, and fathers as fundamental political actors. Is “family values” the conservative rejoinder to the feminist claim that the personal is political?

I never thought of family values in those terms, but I wish I had! I do think family values caught on because it spoke to the hopes and fears of conservative evangelicals in the midst of tectonic cultural shifts.

For instance, the conservative evangelical and Catholic women who opposed second-wave feminists insisted that feminists didn’t speak for all women. When anti-feminist women read Betty Friedan calling suburban homes a “concentration camp” for women, they took it personally. They felt such a statement demeaned their highest calling as women: to serve as wives and mothers.

Leaders of the anti-feminist coalition capitalized on conservative women’s frustration with feminists. Phyllis Schlafly insisted that the Equal Rights Amendment was “anti-family, anti-children, and pro-abortion.” She won broad support from conservative women because she highlighted her commitment to the family and to particular roles within the family: those of wife and mother.

Ironically, identifying first as a wife and mother authorized conservative women to range far outside the home in order to defend their rights within it. Schlafly ran for Congress, authored a bestseller in support of Barry Goldwater, and campaigned across the country to defeat the ERA. Beverly LaHaye gave speeches to thousands. Texas public school watchdog Norma Gabler became a fixture at the annual textbook adoption hearings in Austin, claiming moral authority as a mother to revise curricula according to conservative beliefs.

Stories of these and other women fill the book, suggesting that family values made the personal political for conservative women. They understood feminism as a misrepresentation of their hopes and values, and they rallied against feminist objectives like the ERA and reproductive rights. Being a woman, according to pro-family groups, entailed a noble calling to support one’s husband and nurture one’s children. Feminists who privileged other roles for women were undermining the created order.

Of course, family values crusaders were not immune to the economic pressures that drove more and more women into the workplace in the late twentieth century. Pro-family political rhetoric subtly changed over time to accommodate this cultural shift. By the end of the century, few conservative evangelicals condemned women who worked outside the home. But they retained a belief that women ought to consider their roles as wives and mothers as primary.

That accommodation is interesting. You’ve observed that the defense of the traditional family relied on a declension narrative about post-1960s American life, often with dire warnings about the future. So if the defenders changed with the times, did they ever make any significant concessions? Or, conversely, are there any metrics that they can cite today as evidence that they were right?

The genius of narratives about national decline lies in their malleability. Each new year brought fresh examples of how America was losing its way. While some of the issues that the Christian Right had earlier identified as existential threats (like women in the workplace) became normal, there were always new concerns on the horizon.

It helped that conservative evangelicals were speaking in the language of the times. In his book All in the Family, historian Robert Self demonstrates that the perceived failures of mid-century liberalism pushed family values to the center of American politics in the late 1960s. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 report, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, showed that even liberals thought we needed to bolster family life in America. What was at stake, then, was who would stand up for the family.

We can see this in the abortion debate. Pro-life groups described their opposition to abortion as a defense of both life and motherhood. Obviously, arguing that life begins at conception was a central conviction for the pro-life movement. But a more subtle element of pro-life activism involved framing abortion as an assault on family values. Groups like the Moral Majority didn’t talk about women terminating pregnancies; they said abortions happen “when the mother wants the baby killed.”

This rhetorical description infuriated pro-choice advocates, but it also painted them into a corner. They were defending women’s individual rights in an era saturated by family politics. Either they could defend abortion or they could defend motherhood.

Family values crusaders weren’t always successful in their political campaigns—we still have legalized abortion, after all—but they constructed a vision of family values that brought together a large constituency of evangelicals and changed the way politicians pursued their agendas. This is one metric of their success.

But conservative evangelicals did admit their disappointment at the relative lack of concrete political achievements made by pro-family politicians. They haven’t overturned Roe, returned prayer to public school classrooms, or held the line on gay marriage. At the end of both the Reagan administration and the second Bush administration, a faction of family values evangelicals decided to leave the political arena altogether.

Family values rhetoric seemed to taper off around the turn of the century, to be replaced by “religious freedom” as the key term of the Christian Right. Presumably, though, the movement still thinks family is important. So why make this change now? And will “family values” be back?

Conservative evangelicals have grown more circumspect about their position as political leaders in the last decade. In his book Age of Evangelicalism, Steven Miller shows how evangelical norms, language, and votes exerted a disproportionate influence on national politics until very recently. Miller makes a compelling case that Obama’s election, after running as an “unabashed social liberal,” marked the end of the age of evangelicalism.

More than anything, the legalization of gay marriage signaled conservative evangelicals’ political exile. In the last few years, they have published a spate of books about the need for Christians to live as counter-cultural witnesses, and the battleground has shifted to religious freedom so that [in their view] churches and other Christian organizations can practice what they preach in peace. This is a far cry from the bombast of Jerry Falwell and James Dobson talking about taking back the nation for Christ.

Conservative evangelicals obviously still exert considerable power, particularly in Republican politics. We’ll see that again in the Iowa caucuses and the South Carolina primary. There are still many Republican politicians and evangelical ministers who will get plenty of mileage sounding the alarm that they have been ringing for decades: America is going to hell in a handbasket, and only a return to God will save us.

But will enough people heed the warning? I’m not sure religious freedom as a rallying cry will have much staying power as long as Christian Right leaders continue to apply it with such transparent selectivity. Franklin Graham, for one, has made clear his belief that religious freedom doesn’t extend to Muslims. Other members of the broad pro-family coalition, like Russell Moore, have called out Graham for this double standard.

That’s similar to what’s happening with family values: enough Americans (and enough evangelicals) have decided that the way the Christian Right defined them in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s is too narrow. The pro-family movement is fragmenting.

Family values aren’t going away as long as families exist. What’s at stake is how we conceive of families and their values. The cover of my book depicts a scene at the dinner table of a coal miner in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1971. It’s a visual encapsulation of how Americans thought about family values during this era: white, heterosexual, middle-class, Christian.

The dominance of these demographics is waning. We’ll see the return of family values in our political debates, but they won’t be framed in the same way as they were during the late twentieth century. Over the next few decades, we may be talking about gentrification or incarceration or health care in a family values framework. We can’t predict exactly what shape those debates will take, but it’s a safe bet we’ll be fighting about family values for years to come.

Shares