PORTSMOUTH, N.H. — It sounds way too much like Democratic Party insider baseball to say that Bernie Sanders has made Hillary Clinton a better candidate, and it’s certainly not that simple. Clinton has been doing this a long time, and as she observes at every campaign stop, has been subjected to a level of scrutiny and abuse and amateur psychotherapy almost without parallel in political history. She is of course surrounded by a famously shrewd team of strategists and communicators, who have repeatedly recalibrated her campaign tactics and messaging in the face of Sanders’ extraordinary surge.

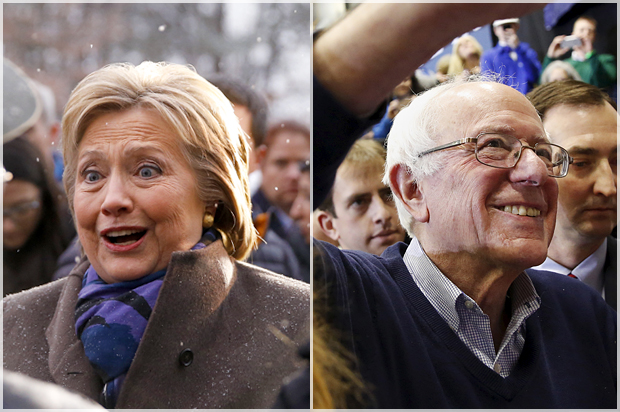

But as I encountered Sanders and Clinton in person over the weekend, the enormous ideological and symbolic gulf between them came into focus. He’s grand and she’s granular, but it isn’t just that. This may be one of those relatively rare cases where differences in political strategy and tactics reflect fundamental issues in this campaign, such as the question of what kind of world these two people imagine and how they hope to build it. Everyone on both sides now assumes that Sanders will win New Hampshire, and move on to more challenging battles in Nevada and South Carolina with some degree of momentum. If he doesn’t win here, or wins by only a narrow margin, the political media will perceive the writing on the wall and they will probably be right.

Make no mistake, Sanders is going for it. His campaign may have begun on a shoestring and a secular prayer, but all those $27 donations you’ve been hearing about have flooded in, and now it’s a highly organized professional operation. At his big rally in the basketball gym at Great Bay Community College here on Sunday afternoon, there were individual workstations set up for every credentialed journalist, with desk space, a power strip and bottles of water. Clinton and Jeb Bush also have loads of money, but they don’t do that. (Donald Trump and Ted Cruz would probably prefer to provide individual waterboarding sessions for the press.)

So when I say that Sanders is going big and going loud, and has pretty much bet his entire campaign on a double-digit victory here and a resultant bump in the national polls, that’s not something a few college kids came up with in a Slack chat. It’s an obvious effort to emulate Barack Obama’s campaign of 2008, and it represents Sanders’ one and only shot at overcoming Clinton’s organizational advantage and her presumed popularity with African-Americans, Latinos and working-class whites across the South, Midwest and Southwest.

Pundits occasionally deride Sanders for delivering the same stump speech over and over, with very little variation. Clinton mixes it up much more, and when I saw her talk to a group of college students on Saturday, she skipped the stump speech altogether. This difference also reflects both strategy and ideology. Sanders has been harping on the same themes ever since he started running for local office in Vermont in the mid-‘70s, and now finds himself in a moment when those issues resonate with an unexpectedly large audience. As a mother of four in her late 40s, who said she had recently switched from Clinton to Sanders, told me in Portsmouth, “Here in New England we’ve known Bernie for a long time. He’s always said the same thing and we know he means it. I don’t feel that way about Hillary.”

At every stop on Sanders’ campaign, he calls for a “political revolution,” castigates the Waltons of Wal-Mart, the richest family in America, for refusing to pay a living wage to millions of their employees, and announces that it’s time for Wall Street banks to bail out working families, instead of the other way around. None of that came as a new idea to any of the 1,200 or so people in that college gym, but that’s not the point. Hearing that kind of rhetoric come out of an actual presidential candidate’s mouth, along with promises of single-payer healthcare and free higher education, is still startling. I mean, it’s startling to different people for different reasons. Younger people may well be startled that such things can even be uttered in American politics. People my age are startled that it’s happening outside some dismal Dennis Kucinich context, where the actual grown-ups who understand politics snicker and nod and say, “Oh yes, in a better world,” and he gets 2.8 percent in New Hampshire and honestly that wasn’t too bad.

Bernie hammering out the same speech over and over again is more than Crotchety Old Guy Repeating Himself, although he sounded even froggier than usual in Portsmouth, after his “Saturday Night Live” appearance and a bunch of plane travel. It’s Bernie insisting that he really means this stuff, and Bernie trying to convince a much larger national audience that such radical visions are no longer beyond the pale. It’s also Bernie, at least by implication, contrasting himself to the seemingly endless ideological fluidity and political calculation of the Clinton family enterprise.

I don’t think it helped either candidate to get into a pissing match over who was a progressive and who wasn’t, but the point Sanders was making is that Hillary Clinton wouldn’t have wanted that label three months ago, and is likely to cast it off again in a general-election campaign. It’s a nettlesome symptom of the widespread perception that she can’t be trusted and has no core beliefs, which Clinton and her supporters perceive as part of the misogyny that has surrounded her career. Both things can be true, of course: Clinton could be victimized by sexist stereotypes and also be a slimy political operator.

If I see potential hubris in the Clinton campaign, it lies in her puzzling inability to perceive that all the campaign donations and outrageous speaking fees from Goldman Sachs and other financial institutions pose a problem for someone running for president on promises of economic reform. I don’t necessarily believe she did anything illegal or nefarious (I mean, beyond the usual intra-elite log-rolling), just as I don’t believe there’s some terrible crime lurking in all those State Department emails. But in both cases she has made the problem dramatically worse through a series of thin-skinned responses, brushing off questions sarcastically or behaving as anyone who inquired about her judgment or integrity were suggesting that a girl shouldn’t be president.

Some of Clinton’s surrogates and spokeswomen, including Madeleine Albright and Gloria Steinem, have gotten into hot water recently, and Bill Clinton was unfortunate enough to launch into a diatribe against the Hillary-hating “Berniebros” of the Internet with a New York Times reporter in the room. But when I saw Clinton herself talking to students at New England College, a tiny school in a tiny town in the western New Hampshire woods, she gave a graceful and agile political performance that also reflected both strategy and ideology. It was an event of ultimate New Hampshire faux-intimacy, a group of 80 or 90 students and faculty surrounded by at least twice that many reporters and camera operators. She remained quietly in control of the room, listening almost as much as she talked and thoroughly disarming a group of young women who had shown up with a list of confrontational questions about GMO foods and transgender rights and various other things.

It struck me that Clinton was trying to accomplish several things at once, the first and most important of those being looking past the peculiar fishbowl of this state toward the Southern primaries and the national stage. I don’t know how the students were selected for this meeting, but a significant proportion of them were African-American, which you would not ordinarily expect to encounter in Henniker, New Hampshire. She talked about Black Lives Matter, mass incarceration and gun control, specifically referring to the Charleston shootings. She had already announced that she would skip campaigning in the Granite State on Sunday to fly to Flint, Michigan, for a series of meetings related to the water crisis in that largely black community. So she was lowering short-term expectations while suggesting a bigger picture: OK, Bernie, you get this one but it doesn’t much matter.

Seriously, Hillary fans, I’m saying that her Henniker appearance was calculated (because this is politics) but not that it was cynical. It never felt that way at all. If Sanders is at his best roaring his big ideas at hundreds of people, Clinton is at her best in this kind of classic retail politics. She began by saying that she knew many young people were supporting Sen. Sanders, and she welcomed hearing their questions. She said nothing negative about Bernie at all, beyond the suggestion that her healthcare plan would work and his wouldn’t. She said that she respected “the strong response that Bernie Sanders has gotten for his attacks on economic injustice and unfairness” and largely agreed with him on those issues, but was better positioned to do something about them.

When a questioner asked her why Sanders had galvanized so many young people, including younger women, and she hadn’t, Clinton stuck to the high road. “I am really happy to see so many younger people involved in politics,” she said, and since that was likely to benefit the ultimate Democratic nominee it wasn’t an “either/or situation.” She reminisced about visiting New Hampshire as a volunteer for Eugene McCarthy in 1968, joking that she wouldn’t have appreciated some older person telling her how to vote. (Memo to Gloria Steinem.)

Clinton always answers questions about her manicured public image and her unique status as a female candidate the same way, and I think it’s time to dump the complicated analogy involving Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. (Not a reference designed to capture the Sanders crowd, I would say.) But the rest of it is killer. “People say they like Bernie Sanders because his hair is a mess and he yells a lot,” she said. “How would that work out for a female candidate? People say I come off as restrained or too careful, and maybe that’s true. I’m trying to become the first woman president of the United States, and there’s no model. There’s a lot of processing that people are doing in their heads. I can see you doing it right now!”

If this was a preview of Clinton’s campaign pitch in March or April, as she (probably) rolls up an imposing lead in the delegate count and begins to tell the Sanders demographic that she’s an acceptable Bernie-substitute who can enact decaf versions of his double-espresso ideas, it was brilliantly executed. Of course it isn’t true. I don’t mean that Sanders can actually bring his socialist utopia to fruition or that Clinton would be the worst president ever. Neither of those things is likely. But there is an important level on which Sanders and Clinton are enemies rather than allies, and it does no good pretending otherwise. There is an immense ideological gulf at the heart of the Democratic electorate that this campaign has exposed, and it cannot be easily papered over, no matter who wins.