Fittingly, given the likelihood that any Democratic president will only be able to pursue their agenda through executive actions and judicial appointments, the 2016 campaign has, in the wake of Justice Antonin Scalia's death, placed the Supreme Court front and center. Indeed, for the first time in a long time, a left-leaning Supreme Court majority seems within Democrats' reach.

Nothing is guaranteed, of course. And Senate Republicans may not even hold a hearing for whomever President Obama eventually nominates. So if Democrats want to have a say in replacing Scalia, they'll almost certainly have to win a presidential election first — at least. Yet even in that best-case scenario, the left may find out that Supreme Court rulings can play out in unexpected ways.

That's the subject, in part, of a new paper from College of Saint Rose professors Ryane McAuliffe Straus and Scott Lemieux. The paper argues that the influence of Brown v. Board — probably the most famous and beloved ruling in Supreme Court history — has not been what most Americans would think. In fact, rather than serve as a tool to fight segregation, there's reason to believe Brown is used to maintain it.

Recently, Salon spoke over the phone with Lemieux about the paper as well as the politics of the Supreme Court today. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

You distinguish between the "iconic" Brown v. Board and the way the ruling has actually operated in American politics. So, first, what's the "iconic" Brown?

When Brown v. Board came up in 1954 it was very important to Justice Warren that [the ruling] be unanimous; but behind the scenes there was actually quite a bit of debate going on. There’s a lot of tension in the Court, not so much over whether Southern apartheid needs to be dismantled — there was a strong consensus by then — but about what the Supreme Court should be doing and how it could do it.

So the thing about Brown and its follow-up, Brown II, is that they said segregation was unconstitutional but said virtually nothing about what school boards are actually required to do. Brown II had that famous phrase “with all deliberate speed” — which is like saying “dry water” or something [similarly oxymoronic]. School boards weren’t really being required to do anything; so for the first decade, Brown just sits there and it’s a symbol but it’s not really providing any influence. So the iconic Brown emerges in the Supreme Court and for 10 years after Brown there is, for all intents and purposes, no integration outside of the border states.

What shifted after those first 10 years?

Once the Supreme Court intervenes with the Civil Rights Act and actually ties federal education funding to desegregation, and also puts enforcement weight behind it; at that point, the Warren Court starts to actually take a very strongly pro-integration view of what Brown means. It’s not enough to just have a formally race-neutral assignment policy; school boards have to show signs that they’re [following it]. It’s not enough to just change your policies on paper; there has to be signs of progress on the ground. This sort of peaks in 1967-68. I think when people think of Brown that’s the way they think of it.

What happened to create the non-iconic Brown, then?

What happened, essentially, is that LBJ screwed up the replacement of Chief Justice Warren. What that meant was that Nixon takes office with, immediately, two vacancies — and then two other long-standing members of the Warren Court die fairly soon after that. So Nixon, in his first term, has four appointments.

A lot of people think of that as not being a big deal because of cases like Roe [which was written by a Nixon appointee]. The kind of people that Nixon appointed were not down-the-line conservatives like Alito or Thomas; but what’s important to know is that, on the issues Nixon cared about, these justices were very conservative. Bussing and civil rights were some of the issues Nixon cared about. They could be liberal on abortion because that was not on Nixon’s radar when he was making those appointments.

So what did Nixon's appointees do?

Nixon’s justices, along with one Republican holdover, were responsible for two really important Supreme Court cases in 1973 and 1974. The first of those, San Antonio v. Rodriguez, upheld the use of local property taxes to fund schools. So under arrangements like that, which are very common, the wealthier the district, the better-funded its schools. Essentially, educational opportunity would be unequal; and considering the high correlation between race and economic disadvantage, this would also have distinct implications for segregated schools.

In the case of 1974, Milliken v. Bradley, which was based in the Detroit area, the Supreme Court said that federal judges could only make integration plans for individual cities and not for metro areas as a whole. So if you have an inner city that’s 90 percent African-American or Latino and suburbs that are 98 percent white, the federal judge can’t take that into account. They can integrate the urban schools, but since there are very few white people left in the city [due to "white flight"] that’s a meaningless standard.

Since then, there’s been a roadmap for how states can have de facto segregated schools without attracting judicial attention.

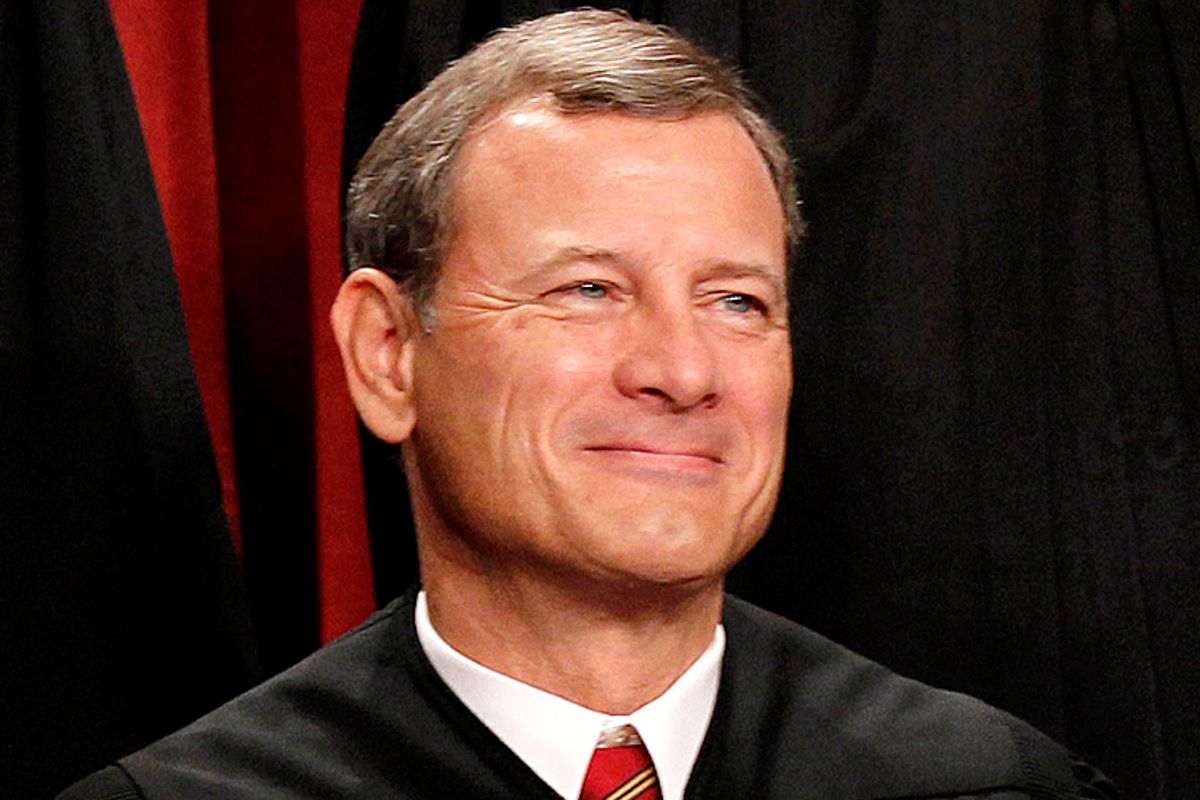

Which suggests that the Court's recent rulings on race politics are not quite the break from precedent that many people assume, right? If the "iconic" Brown was never really much of a force, judicially (as opposed to politically or culturally), then the Roberts Court's rulings aren't necessarily so out of the blue.

That’s it. No Supreme Court justice has ever called on Brown to be overruled; anybody that said Brown was wrong would have no chance of being confirmed. But that’s in part because, from a conservative perspective, it’s been rendered harmless — and, indeed, it’s been used as a weapon.

Chief Justice Roberts famously said, “The way to stop discriminating on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” That’s the conservative reading of Brown: that all that matters is that districts not take race into account. The problem with that is, when you have a history of racism, refusing to consider race just reinscribes patterns of segregation.

What should those who want to see the "iconic" Brown become the "real life" Brown do?

One thing to remember is that affirmative action cases [from the Supreme Court] right now are very closely divided. I’m not saying it’s going to be easy to get back to where we were in the late '60s, where federal courts are routinely issuing supervisory orders. But if Scalia’s replaced with any Democratic nominee, we can certainly get things going in the right direction.

Speaking of Scalia and the Supreme Court, what are your thoughts about the likelihood of Obama replacing Scalia? You've written that this is essentially a slow-moving but inevitable constitutional crisis; has anything that's happened since the news first broke changed your view in that respect?

I would say no. I have a bigger piece about this in the American Prospect, but if you look at some of these walk-backs [from Republican senators], I see no sign that they’re open to actually confirming somebody. It’s more like, Should we be completely explicit that we’re going to serially reject anybody? vs. Should we go through the motions of holding hearings and then discover that obviously this person is a radical anarchist that is unfit for the Supreme Court?

I just don’t see any way that there’s a deal here, and the fact that McConnell immediately started out by saying [the Senate] wouldn’t confirm anybody, that indicates there's a strong consensus [among Republican senators]. And from the standpoint of the conservative base, I don’t even blame them.

Why not?

Choosing Scalia's replacement is a pretty big deal! [laughs]

The median vote of the Court shifting that far left is not a minor thing. I think that they’re correct in assuming that [criticizing Republicans for not allowing a hearing is] not a positive for the [Democrats'] Senate campaigns in New Hampshire and Illinois and the other purple states; so my guess is that they sit tight.

Is there any way it wouldn't be the worst thing in the world, from the Democrats' perspective, to have a Court that produces 4-4 rulings? In those cases, the law becomes whatever the appellate court decided beforehand, right?

One really major important development of Obama’s second term was the use of the "nuclear option" to make sure that the D.C. circuit was staffed. If there’s anything that can possibly lead to the Republicans agreeing to a Democratic nominee, it’s that the D.C. circuit right now is tilted towards Democratic nominees.

Why is that so important?

Because that’s the circuit that deals with federal regulatory cases.

So it’s true that a 4-4 Supreme Court would be not nearly as bad for Democrats as it would have been five years ago; the federal courts, in general, are much less tilted towards conservatives than they were before. At least on some of these challenges to regulatory policy, having that Democratic majority at the D.C. circuit means there’s a limit to the damage that a 4-4 Supreme Court could do. A 4-4 Supreme Court with a Republican majority in that circuit — that’s a catastrophe.

Shares