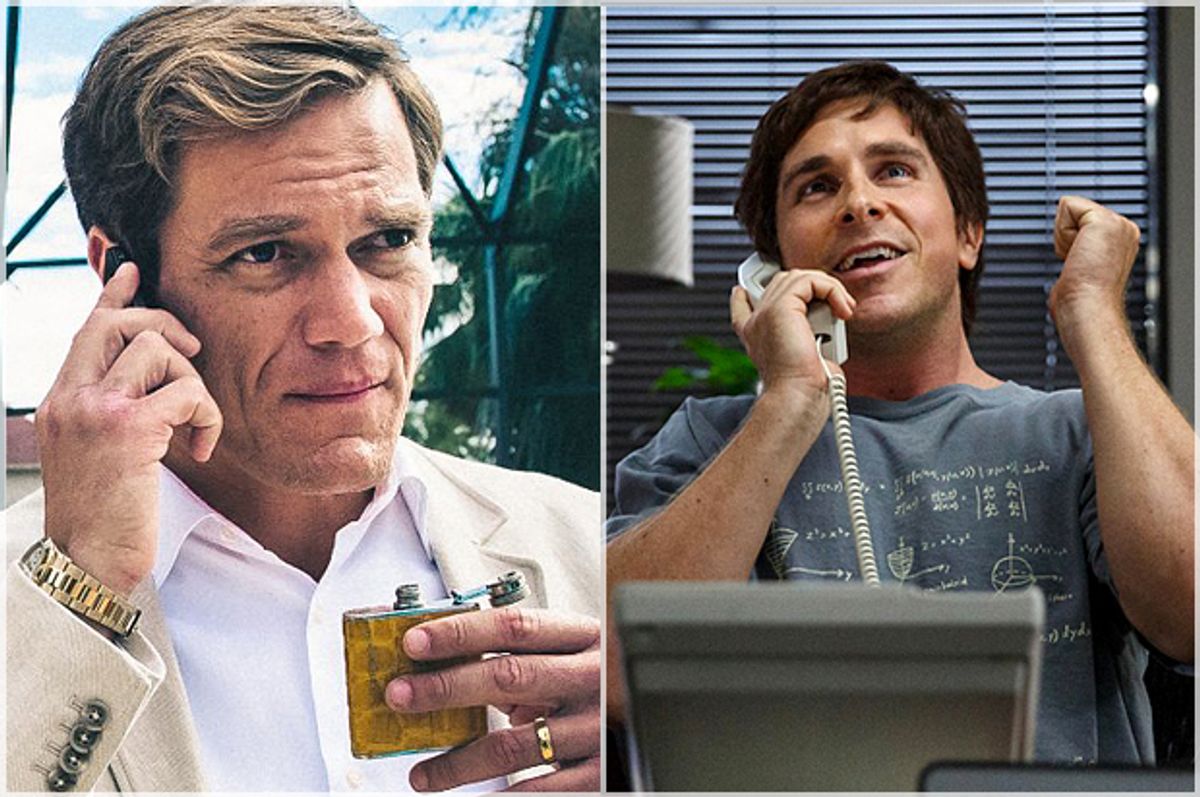

"The Big Short" is a sly film. Based on a Michael Lewis’s novel of the same title, "Short" interweaves a bushel of megawatt-charged pop cultural devices to explain the driving forces behind the Wall Street financial meltdown of 2008.

Perhaps we didn’t pay nearly enough attention to the millions of pages of studies, articles and books, all of which persuasively argued that our country’s housing market crisis was evident well before the 2008 meltdown. Perhaps our favorite digital and sitcom distractions had something to do with this neglect. But in 2016, eight years later and with the repercussions still felt, "The Big Short" has a nice late-game solution to all of this: a ton of people would go check out a film on finance in which an A-List dream team cast of Christian Bale, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling and Brad Pitt are the leading Wall Street warriors.

According to "Short," however, not even this line-up may be enough to hold the audience’s attention. We’re an ADD-addled generation so prone to jumping onto YouTube for a cat video every 10 minutes that an animatedly excitable Christian Bale may not be enough to pique our interest. So the film compensates with a bunch of little YouTube-style vignettes here and there. Margot Robbie shows up in a bubble bath to explain sub-prime lending. Selena Gomez dazzles in a chic evening gown to discuss collateralized debt obligations. In "Short," the audience is never asked to focus on one thing for too long.

However, there is a necessary trade-off here. For every crummy reveal, there’s a delicious movie-moment speech, a quirky pop star, or a ritzy Manhattan setting to temper any lasting feeling of disgust. In this regard, the cleverly delivered message in "The Big Short" — that we tend to easily forgive the charismatic for their misdeeds—is also what makes the film itself a little sneaky. "The Big Short" knows when to hedge its own bets, and its reasons aren’t too different from the finance sector’s ultimate goal.

For instance, midway through the film, Steve Carrel and his posse of comically foul-mouthed brokers take a trip to Florida to see what’s really going on in the housing market crisis. We get a brief glimpse of a land ravaged by banking foreclosures and vulturous brokers dealing away even more fiscally irresponsible sub-prime mortgages to buyers with highly questionable financial qualifications. There’s a promise that things are about to get very dark and unbearably true in Florida, and in an awful hurry.

But in a quick turn of events, we see Carell uncomfortably receiving a lap dance at a Florida strip club. His dancer has some intel on just how frighteningly out of control predatory mortgage agreements have gotten. As soon as Carrel gets his intel, he scurries back to his posh NYC office so he can bet heavily against the banks.

Carell’s animated discomfort is played for laughs — here’s America’s favorite social-phobe getting an uncomfortable lap dance. As a result, we quickly lose traction over what we’re really supposed to be feeling uncomfortable about: those increasingly desolate suburban streets and the evicted homeowners who are scrabbling about for answers, or at least a voice.

***

Where "The Big Short" hedges, "99 Homes" goes for broke. In "Homes," unusual lengths are taken to give foreclosed Florida homeowners a sympathetic voice, even if at the great risk of relentless earnestness or tragedian tones.

Set in Central Florida against the backdrop of the 2008 housing market crisis, the film follows cold-blooded real estate agent Rick Carver (Michael Shannon) as he, along with two stone-cold police officers and a roughneck construction crew, forcibly evict countless panic-stricken families from their foreclosed homes. One of Carver’s victims, Dennis Nash (Andrew Garfield) — a jack-of-all-trades construction worker living with his mother (Laura Dern) and his son (Connor Nash) — compromises his moral indignation to join Carver’s crew in an effort to reclaim his home.

While "The Big Short" delivers some rapid-fire speeches about Social Darwinism in ritzy clubs and boardrooms, "99 Homes" goes into painstaking detail to account for just what Darwinism means to the working American family.

Here are families begging a broker and police officers for more time until their legal appeal is decided, only to be met by precisely scripted denials, recitations of court-ordered procedure, and harsh ultimatums: get out, get your stuff, or we’ll force you out. There’s no cut to Margot Robbie in a bubble bath. Rather, we stay on Laura Dern slowly sinking into utter shock when it finally hits her that, yes, she has only two minutes to get her grandson’s clothes and blankets before a police officer moves her to the curb.

"99 Homes'" big bet was on emotional continuity. After their eviction, the Nash family scurries to a motel, which evokes a nightmarish scene reminiscent of Steinbeck’s depiction of migrant camps in "The Grapes of Wrath." It’s overpopulated with recently evicted homeowners clustered on balconies. Nash’s tiny room, with its cheap mattresses and paper-thin walls, won’t protect the family from the bubbling rage just outside: profane tirades and loud music that will carry on throughout the night.

Nash’s quick decision to join Carver’s crew is based on a survivalist impulse. There’s no time to ruminate on Carver’s various fraudulent practices and icy mantras. Nash has a son he wants to provide a stable home for, and he needs money fast to buy a new one. Nash can only do what he feels he needs to do, and feel awful about it. Yes, Nash’s face is racked with pain when he forcibly evicts a senile old man who has absolutely nowhere else to go. But he does so anyway, continuously clinging onto an advantageous side of a zero-sum game for as long as he can. The audience is challenged to stay along for the ride and emotionally experience some tough questions of their own.

***

"The Big Short" is everything audiences instantly covet in a film: star studded, not unintelligent, and not too much of a bummer; that paid off handsomely. The film’s release peaked at 2,500 theaters and it has raked in $66 million and climbing at the domestic box office. The Academy has lavished "Short" with five Oscar nominations, and it’s generally considered one of the top contenders for best picture.

"99 Homes" is a universally acclaimed film, with a 91 percent approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and a slew of deeply felt reviews. It is a deeply American film in that it deals with property ownership over a diverse racial and age demographic. And yet, it suffered terribly at the box office. That’s not entirely due to lack of distribution. "99 Homes" was released in 640 theaters nationwide, certainly not an anemic number. Still, it is currently taking a loss at the box office, having earned only $1.4 million domestic on a $8 million budget since its September 2015 release. Like thousands of foreclosed homeowners with little to no voice in the system, a film about the same also faded into oblivion.

"99 Homes'" lack of commercial momentum enraged Oliver Stone, who called Shannon's performance "as exciting and visceral as Gordon Gekko in 'Wall Street.'" But really, it shouldn’t only be about what Stone has to say. It should be about how we each individually look at our preferences, and what they mean toward changing the current homogenization of our film industry, even beyond the overdue scrutiny of Hollywood diversity and #OscarsSoWhite.

The gross disparity between "The Big Short" and "99 Homes'" commercial success speaks to what’s arguably the encompassing problem: the American film market is focused on entertainment not only from a single race and gender, but from the same iconic stars, from the same big cities, and from the same formulaic lenses used to deliver the same derivative story lines. As a result, innumerable stories about massive components of America continue to be grossly unrecognized.

Admittedly, I helped perpetuate this cycle in December. Like most Americans, my bank account is closer to the characters in "99 Homes" than the mega-millionaires in "The Big Short," which is to say that I can’t afford to hit the movie theater too often. Still, when it came time to drop $15 on a matinee this December, I went past one "Big Short" billboard after the next, straight to the theater. I didn’t even consider "99 Homes."

When "99 Homes" was finally released on demand, I shelled out $5 to see it in my apartment. But that’s still $10 less than I spent on "The Big Short," and well after the box office numbers had already left their mark.

These choices I made are important, and have left on impression on me since. How I--and other moviegoers--choose to spend time in the theaters will be the single most important factor in determining the direction of film production and distribution over the next few years — perhaps bringing about a greater emphasis on racial, economic, gender and geographic diversity that will be necessary to bridge the gap between the "99 Homes" and "The Big Short"s of the world.

Shares