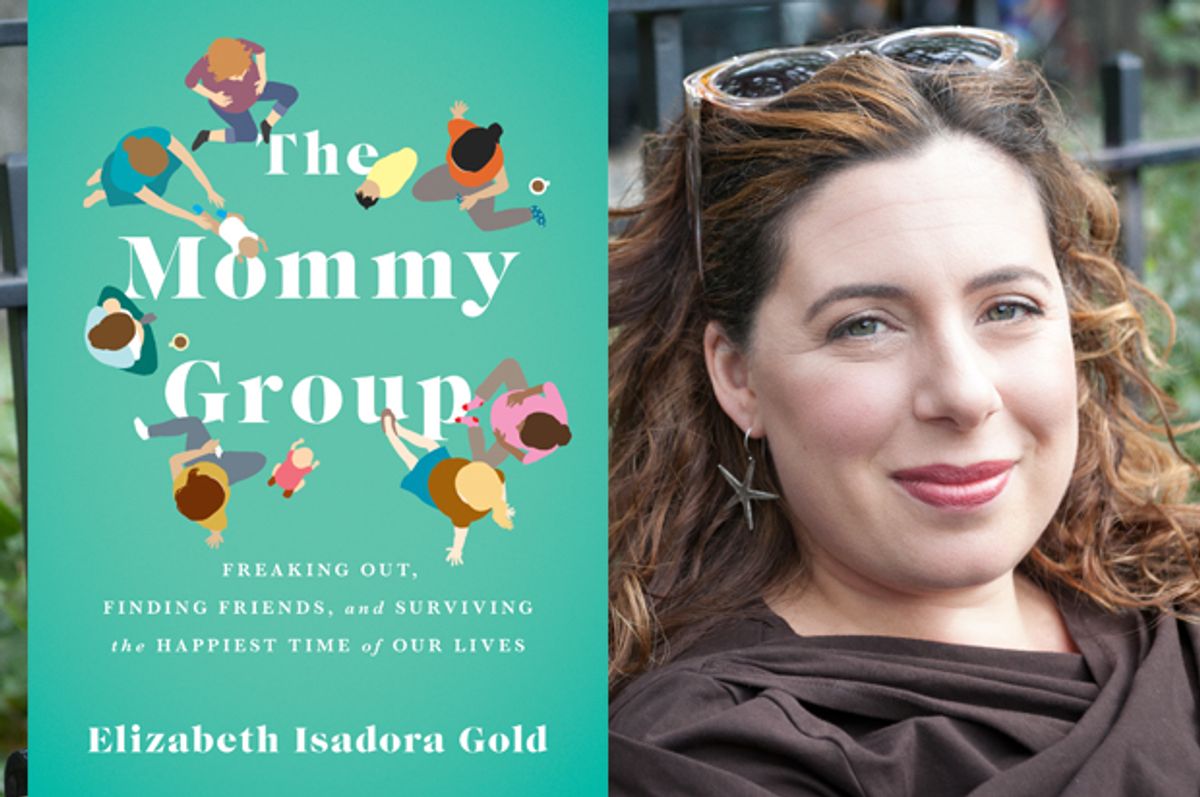

Elizabeth Isadora Gold knows that her new book, “The Mommy Group,” might be a bit daunting to those whose lives don’t include any babies at the moment. “I’ve been calling it a non-invasive IUD,” Gold says, with a wry laugh. Blending elements of memoir and journalism, the book follows a group of seven Brooklyn women who came together in 2010 to share their burdens during pregnancy, childbirth and their babies’ first year. Overall, they’re a privileged group – well-educated, healthy and financially OK (though some are more OK than others) – they’re all straight and most are white. But the struggles they face are those that can happen to all mothers, from all backgrounds; throughout the book, we see them work though infidelity, birth trauma, postpartum depression and parenting children with developmental disability.

There’s a lot of humor in “The Mommy Group” – when you’re getting sleep in one-hour chunks and feel permanently connected to a breast pump, you pretty much have to laugh to keep from crying – but Gold has a serious message, too. By telling our stories, she argues, women can not only support each other but push for political change as well.

Are you still close to the women in your Mommy Group?

We are still very connected. I’m in very good touch with everyone. In any given week, my daughter will have playdates with three or four kids within the group. These are some of my closest friends. Which made it, not incidentally, fairly tricky to write about them.

I was wondering about that – how did that process go? How much did you check in with them? Did you worry about self-censoring?

It was hard. I have a very formal nonfiction background. I have this very specific ethos of nonfiction writing, that not only do you have to be truthful, but that you have to push really hard to get the internal truth. I had thought almost from the beginning of this group, oh my god, this is a book. I sort of jokingly would be like, I’m going to write a book about us! And they’d be like, yeah, yeah. Because they didn’t really know me as a writer, they knew me as a pregnant and then breast-feeding person. And then when I said, no, actually, I’m really going to write a book about us, I asked everybody for permission. I said, I’m going to interview you. I asked everybody how they felt. We agreed that names and identifying details would be changed – professions, some details about neighborhoods. It’s not far from who they are. Everybody sat for interviews. Everybody was very open. All the dads had to be on board.

I had been so nervous that they were all going to hate me at the end of this, that I had been really scrupulous about the facts. I knew I had to be emotionally on point and not cover up for what people’s unhappiness or dissatisfactions had been. And that was tricky, especially talking about people’s husbands. But I made sure that everybody felt good about it – and they’re smart women, they understood that this was going to contribute some record of what it’s actually like to be a mom. It’s really special to me that they all felt like they were participating in something that was bigger, that wasn’t just me getting to write a book, but that had like a higher purpose, not to be too arrogant about it.

The book has a lot of light moments and a lot of humor, but you write really honestly about falling apart, postpartum, and being on a daunting cocktail of drugs. What did it feel like to write about that, and how are you doing now?

The book coming out is fairly concurrent with the fifth anniversary of getting postpartum. I’m still on the same cocktail of drugs. I don’t consider myself recovered; I don’t consider that I will ever be recovered. I don’t consider that there’s such a thing as recovery – I think that you grow and you change and you learn more about yourself. Postpartum got me back into therapy after a few years of not being in therapy. I’m definitely a person who ought to be in therapy.

For me, the radical honesty approach is definitely the best approach. I have no compunction about telling people what medication I’m on, and why, and what happened. This doesn’t hold true for everybody, but it makes me feel less anxious to just be like, this is where I’m at, this is who I am.

One of the things I think the book captures is how you can have all these theories about what’s right for kids, generally speaking, but then when you meet your own child, get to know your own child, you realize there are like 20 different right answers to any problem, and it all just depends on your own kid and your own family.

I feel like a lot of what I learned having postpartum was that I had to give up a lot of the ideas that I had about being the mom of a little baby and what that would look like. And it was bad for me, in terms of the fact that I was mentally ill, but it was not bad for Clara. Nothing happened that was bad for her in that scenario. I had to deal with being sick, but she was fine. It wasn’t like any decisions were made that weren’t optimal for her. In a weird way, I think – and I talk about this in the book – I think the fact that she had so many caregivers early on. She would have had a good relationship with Danny anyway, because he adores being a father and wanted to be an equal partner always, but I think she has a particularly exceptional relationship with him, because he had to do a lot of mommy-style caregiving for her.

One of the things you talk about in the book was the level of honesty that your mommy group was able to come together with. The ability to share even the ugly stuff is so affirming and so crucial to building a community, because being a mother is really hard and you’re expected to think it’s all sunshine and roses, when you’re just freaking out.

I can’t help but think of the crazy election, this crazy political moment that we’re in, people talking about Hillary Clinton being held to a higher standard because she’s a woman. I think there’s some truth to that. I think women are held to this higher standard in terms of not letting them see you sweat. I think it’s really important to let them see you sweat, because that’s where change comes in. Conditions for working mothers have not really improved since the 1980s. We don’t have maternity leave, we don’t have subsidized childcare, our reproductive rights are still up for grabs in dramatic ways, we still don’t have financial parity. This is especially true for poor women, and there are more poor people in this country, proportionately.

There’s too little support in a profound way, a profound way. That is part of what this book is about – that the process of becoming a mother is so difficult and complicated, physically, emotionally, and we’re so not supposed to talk about it. We’re not supposed to say, the day I became a mother I wasn’t the same person ever again. I’m different, I’m a different animal now. You know, we’re not supposed to admit that. But it’s hard on your body. If you’re trying to work and pump breast milk – it’s so weird and uncomfortable.

And the lack of sleep, and the million other decisions you have to make every day that you didn’t even know were decisions you had to make, like what’s my approach to this parenting dilemma, what’s my strategy? I remember when my children were little, tiny, I would always walk around knowing which ones of their fingernails and toenails I needed to trim. Like I could get five fingernails done before somebody would start crying, and then in my head I would think, I’ve got to go back and get that nail.

Tina Fey has this great part, I think in "Bossypants," where she talks about how the only time she was able to trim her daughter’s fingernails was while her daughter was pooping on the potty. This became her thing that she did. And she was like, how did I become the person who trims her daughter’s nails while she’s pooping? That’s parenthood. And I think that’s particularly working motherhood, you just catch as catch can in this really intense way. And that’s the part that really you don’t know about until you’re in it. You think, well, I can manage it. I can deal with little sleep. And it’s not that – it’s the feeling that you really are walking around with a piece of you across the city. It’s a really strange feeling.

In the book one of the moms says, “It’s like being on an acid trip all the time.”

That sentence got us through the first year of parenthood!

It’s like your brain has been so radically rearranged, it’s almost not worth trying to go back. It’s like, how do I navigate the new normal?

Yes. And that’s my theory in the book, is that it takes a full two years. I have a friend who adopted a 2-year-old, and I feel like, it was still two years before she felt like she had kind of gotten not only in the swim of being a mom but also felt like she could get her Self, with a capital S, back again. Two years isn’t that long in the grand scheme of things, but you need it, you need to go through a process and figure out who you have become, because you’ve become someone different.

When you’re in it, the two years feel endless. And at the end of it – I think it’s important, that point about self. Between our sexist society, and feminist messages about how women can and should be in the world, it can feel hard to calibrate – or it’s hard for me, anyway – how self-centered I’m allowed to be and still feel like a good mother, or wife, or friend, or employee. You sacrifice yourself for your child all the time. But as some people will very wisely say, you have to put your oxygen mask on before you help others. It feels like a complicated decision on a day-to-day basis.

It is. Obviously it depends on what your capabilities are. This is one reason mommy groups are so great. Because you can be with the kid while you’re also taking care of yourself. And that’s helpful, because you don’t have to feel guilty about the not spending time or the childcare aspect, you can get the adult conversation and the support that you need at the same time.

But it’s a day-to-day set of decisions. And, I have to say, these are a privileged set of decisions. Many, if not most, women in this country don’t have a choice about whether or not they’re going to have a nanny, or keep the kid an extra hour in daycare, or take a personal day when the kid is sick. Many, if not most, women in this country are in such a state of financial insecurity that they just have to do whatever they have to do – if they take an extra personal day, they lose their jobs. Emotionally, I think it’s a wider problem. But having the privilege to be able to decide these things – sadly, it’s kind of a nice problem to have.

And again, if we had the basic laws in place that we needed to have, then the conversation could be more about what is the emotional quality of parenting. What’s the emotional quality of life as parents, what’s the emotional quality of motherhood? Then we would be able to work on the other parts of the conversation, which could be much more about, what can we achieve as women, what are our goals, post-parenthood, what do we want that life to look like? But until we have the legal parts in place, it’s catch-as-catch-can for most women.

Do you think this society is ever going to be as structurally friendly to families as, say, Scandinavian countries are?

I hope eventually, someday. But I don’t know. We have a big, not-homogenous country, with a great deal of hostility toward the idea of giving anyone “extra” support. I teach college students, and their ideas about the world are quite different than mine. I think they have this acceptance that it’s not looking like they’ll be able to do everything. I think that they’re still waiting, too. I look at my college students now, who are maybe going to have kids in another 15 years or so, and I have no idea what’s going to happen. Who knows? You have to put a value on children – and you have to put a value on education, you have to put a value on women’s agency over their own bodies, if you want to put a value on motherhood, which in turn values children. The conversation is very broad, and it’s either super-complicated or so simple that it’s ridiculous. The fact that gender issues are so huge in this election and that people still don’t understand that women simply don’t yet have equality – and we’re arguing over the Supreme Court, the idea that something has to be pro-woman, that there still exists a land where …

We’re still a special interest!

We’re still a special interest! We’re the majority at this point! Most people in college are women, most people in grad school are women. It doesn’t make any sense whatsoever! So this, to me, is the broader message of the book. I was raised by a third-wave feminist, I was a women’s studies major at an all-women’s college. We need to organize; we need to talk to each other. Because if we don’t, then we’re all in these little isolation tanks thinking that we’re the only people who have the feelings that we have. And that goes for trying to get pregnant, miscarriage, breast-feeding, going back to work – all of this stuff, if you walk around feeling like your individual body is the only body that’s having this stuff happen to it, you’re going to feel crappier. And nothing will ever change.

Shares