Two of the books on many of the best-of-2015 lists were written by women who died in virtual obscurity, Clarice Lispector in 1977 and Lucia Berlin in 2004. The republication of their stories was big news last year, bringing them to the mass audiences denied them in their lifetimes. Lit Hub even declared 2015 “The Year of Rediscovered Women Writers,” in its list of the top five literary stories of the year. How could these gifted writers have been erased from history, so many wondered? We shouldn’t be so surprised. There are many worthy writers languishing in moldy archives, and I would venture to say that the majority of them are women.

Feminist scholars spent much of the 1980s and 1990s recovering forgotten women writers, generations of Shakespeare’s and Melville’s sisters, as some called them. But virtually all of the dozens of writers they reclaimed, with the exception of Zora Neale Hurston and Kate Chopin, never made it out of academia’s cloistered walls and into the public consciousness. As a result, many of them are disappearing again.

A case in point is the phenomenally talented American writer Constance Fenimore Woolson, one of the most highly regarded American writers of the 19th century. Critics hailed her as America’s “foremost novelist” and the only American woman writer in the same league as George Eliot. Her friend Henry James paid tribute to her in his collection "Partial Portraits" (1888), finding in her stories “a remarkable minuteness of observation and tenderness of feeling on the part of one who evidently did not glance and pass, but lingered and analyzed.” After Woolson’s death in 1894, her editor at Harper’s, which had an exclusive contract to publish all of her writings, called her “a true artist” whose writings possessed a “rare excellence, originality, and strength [that] were appreciated by the most fastidious critics.”

Yet, almost as soon as she died, Woolson faded from view, so much so that her closest successor, Edith Wharton, never acknowledged her existence, despite the fact that they shared a close friend (James) and Wharton must have been aware of Woolson’s work. But Wharton was keen to distance herself from other women writers, just as they were being relegated as a class to the dustbin of literary history. At the turn of the 20th century, the cadre of male critics and scholars busy forming the American literary canon decided to completely ignore all of the dozens of women writers who had made names for themselves since the Puritan Anne Bradstreet. Emily Dickinson and Wharton were let in later, although as anomalies. And for nearly a century, it appeared as if women writers simply didn’t exist, except perhaps as third-rate magazine writers who churned out sentimental drivel.

The writings of Woolson and many other significant American women writers of the 19th century were simply left to molder on library shelves for feminist scholars to discover them. As they brought these texts out of the mothballs, cries of “but are they any good?” echoed in the scholarship of the period. Some texts, particularly those by early American women writers, could only be reclaimed by reformulating literary value, privileging cultural work over time-bound aesthetic criteria. Others were considered worthy of comparison to canonical male writers such Emerson, Hawthorne or James. In this way, Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Stoddard, Sarah Orne Jewett, Mary Wilkins Freeman, Woolson and others were brought back into print in their own volumes or in anthologies. The reputations of Jewett and Freeman have been particularly well recuperated. But Fuller, Stoddard and Woolson, or many of the other extremely talented women writers rediscovered in the 1980s and '90s (such as Rose Terry Cooke, Frances Harper, Rebecca Harding Davis, Sui Sin Far or Zitkala-Sa), may go back into the black hole of unknown women writers once again.

In Woolson’s case, her story “Miss Grief,” a masterpiece about women’s thwarted literary ambitions, has gone into college anthologies only to be pulled out again by some of them. In addition, Woolson, who wrote five novels and four collections of short stories, has not had any work in print for many years. One difficulty is that she cannot be associated with one place, as she set her fiction in many different U.S. regions (all over the Great Lakes and Reconstruction South), as well as in Europe. Another major problem is that Woolson has been left out of the feminist reevaluation of regional literature, a so-called minor genre of primarily women writers, despite being a pioneer. Why? She was too “male-identified,” one prominent feminist scholar told an audience at a conference sponsored by the Constance Fenimore Woolson Society. Because she was very close to Henry James, courted the opinion of male critics, wrote many of her stories from a male point of view, and did not participate in female literary communities, Woolson has been left out of the feminist celebrations of regionalism that have brought renewed attention to so many important late-19th-century women writers. Her case makes clear that a writer’s lasting reputation does not rest solely on the so-called quality of her work.

As the cases of Lispector and Berlin show, however, the surest route to recuperating a writer’s reputation is not through academia. It wasn’t for Zora Neale Hurston, either, who was first rediscovered by Alice Walker and then picked up by scholars. Academia is fickle in its allegiances. The movement of feminist criticism that brought so many of Melville’s sisters back into the light had a profound impact on the way literature is read, but its legacy is unclear. Many English department faculties have simply left the teaching of women writers to the feminist faculty, who are retiring now in large numbers and are not necessarily being replaced.

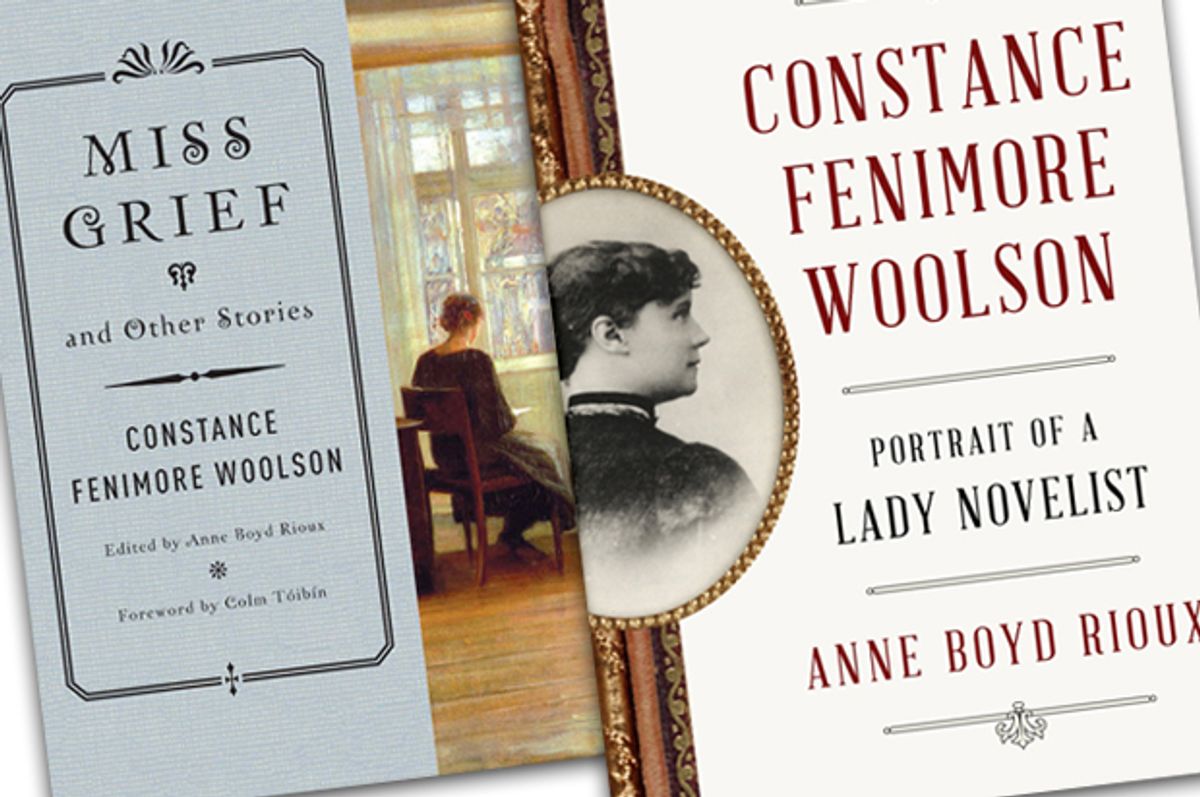

Astonishingly, some of the literature professors who spearheaded such rediscovery work have said that their jobs are done, their goals accomplished, that we are in a “post-recovery” era. What they did not foresee is that their gains could be reversed. Until these women writers gain a wider readership of those interested in American literature, they might very well be lost again. A writer like Woolson, whom Colm Tóibín compares (in his foreword to "Miss Grief and Other Stories," the new collection of Woolson stories I have edited) to Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield, could again fade into obscurity.

As a result, today’s women writers will continue to feel that their literary foremothers are few. As Claire Vaye Watkins recently reminded us in her essay “On Pandering,” such a vacuum leaves women writing in a sea of maleness, as if literary greatness was the prerogative of the male gender and the gains made by Woolson and her peers never happened. Unfortunately, despite the hard work done to bring back important women writers, we are not there yet. Far from it.

Anne Boyd Rioux is the author of "Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist" and the editor of "Miss Grief and Other Stories," both out now from W. W. Norton. She is also a professor at the University of New Orleans and the recipient of two National Endowment for Humanities Fellowships, one for Public Scholarship. She can be found online at http://anneboydrioux.com/ and on Facebook and Twitter.

Shares