In 2004, John Kerry neatly summarized what had come to pass for liberal anti-war sentiment: Bush “rushed the nation to war” in Iraq and “took his eye off the ball—off of Osama bin Laden.” Kerry — who, in a high-point of craven pandering, saluted on stage at that year’s Democratic National Convention, announcing that he was “reporting for duty” — had voted for the Iraq war as well. But he was advancing the long-held conventional liberal wisdom, that Afghanistan was the good war, and Iraq the bad one.

The Democrats were trying to walk a political tightrope between rising anti-Iraq War sentiment and persistent fears of terrorism, a political climate that seemed to demand a president of wartime stature. And so Kerry, the onetime winter soldier who during the Vietnam War asked Congress, “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake,” was now a hard-nosed realist, wise to the fine balance between too much force and too little. Obama repeated the sentiment just before he took office in 2009, saying, “We took our eye off the ball when we invaded Iraq.”

But what has passed for conventional liberal wisdom then has been proven unequivocally false. And, in the meantime, it has wrecked American foreign policy and much of the country’s political culture as well, narrowing the scope of an anti-war movement that ultimately collapsed, and enshrining the Global War on Terror as an ultimately just pursuit that neoconservative ideologues had unfortunately run off the rails.

The invasion of Afghanistan, unlike that of Iraq, had a fig leaf of moral rationale: Al-Qaeda, sheltered by the Taliban government, killed nearly 3,000. But that war’s outcome, as a minority of very lonely critics predicted, has nonetheless proved a similarly bloody and regionally destabilizing mess. A May 2015 report from Brown University’s Watson Institute estimated that roughly 149,000 people died in war-related violence in Afghanistan and Pakistan—alongside what may be many hundreds of thousands more indirect deaths, caused by collapsing health infrastructure, malnutrition, displacement and other war-related maladies. Today, the central government foisted into power by NATO occupiers has committed atrocious human rights violations; while Pakistan, the subject of widespread U.S. drone warfare, has been sent into a perilous spiral of violence. Meanwhile, as the Washington Post neatly put it this past January: “The Taliban is stronger than ever.”

In retrospect, this is hardly surprising. But September 2001 was a lonely time to oppose war in the United States, as the few who protested against the invasion no doubt remember. American flags were plastered everywhere and a jingoistic and militaristic rhetoric predominated that not even today’s ISIS hysteria comes close to rivaling. The vote authorizing a military response passed without opposition in the Senate; in the House, it was opposed by just one legislator, Congresswoman Barbara Lee (D- CA).

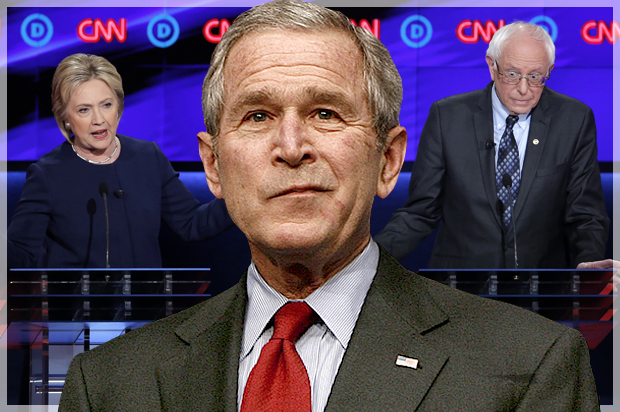

Much of whatever political left existed at the time fell in line after the Twin Towers came tumbling down. Bernie Sanders voted yes, though he warned that “widespread and indiscriminate force could lead to more violence and more anti-Americanism.” Dennis Kucinich voted yes. Lee, however, was prescient.

“I am convinced that military action will not prevent further acts of international terrorism against the United States,” Lee argued on the House floor on Sept. 15, 2001. “There must be some of us who say, ‘Let’s step back for a moment and think through the implications of our actions today — let us more fully understand the consequences.'”

The unity of the bipartisan national security state began to crack when The Patriot Act was passed in October. But not much. It passed the Senate with just one dissenting vote (and Hillary Clinton’s support) and sailed through the House with just 66 voting in opposition (Sanders among them). George W. Bush’s approval ratings reached 90 percent.

Yet, in toppling Afghanistan’s government, the United States not only failed to crush Al-Qaeda; rather, it set in motion a chain of events that has created new terrorist groups and warfare worldwide that are killing people in Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Today, the Authorization to Use Military Force continues to be used to justify warfare in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, Syria and Iraq, according to a Congressional Research Service overview.

At home, the terrorist attacks since September 11th have been few. But the political costs have been enormous. The liberal allegiance to the Afghanistan invasion hemmed-in the scope of an anti-war movement and, in spreading conflict globally, undermined that movement’s ability to put forth a coherent platform. Hillary Clinton, one of the most hawkish Democrats alive, is now on a path to clinch the Democratic nomination. Her success is a direct result of the demise of an anti-war movement that, if it had been more powerful, would have successfully painted her as a dangerous militarist.

It’s long past time to acknowledge not only that the Afghanistan proved to be a failure, but also that it was unjust and misguided from the outset. Action against Al-Qaeda was justified. But the toppling of an entire government, predictably plunging a region into war, was both wrong and unwise. A just and sane foreign policy will be out of reach until we have an honest reckoning about Afghanistan.