Commencement

I sank, exhausted, into the backseat of a small sport utility vehicle as it pulled onto a sparsely populated Wyoming highway, finally getting some rest after a long day. As I opened the window to get some air, the desert breeze awakened me to the most beautiful sunset I had ever witnessed. The sky was a mix of purple, blue, and pale orange, made even more vivid by the light brown dust on the side of the road and the gray asphalt stretching out ahead. Soaking up that beautiful sky, I thought about the teachers I had met that day. They were mostly white middle and high school teachers who taught science and mathematics to Native American students. I had been invited to Wyoming to deliver a lecture about ways to improve teaching and learning in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), and spent almost forty-five minutes after the hour-long lecture answering a host of questions about strategies for engaging students and teaching them more effectively.

As I marveled at the passing scenery, two things occurred to me. The first was that these teachers had a genuine love and concern for their students. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t have shown up at my lecture and asked so many questions. The second thought, which seemed initially to be unrelated to the first, was that I was driving over land that belonged to the same Indigenous Americans whose descendants I was preparing these white educators to teach. As the colors of the sky slowly deepened, I thought again about the follow-up questions the teachers had asked: How do we get disinterested students to care about themselves and their education? Why are our students not excited about learning? Why aren’t they adjusting well to the rules of school? Why are they underperforming academically? These questions were remarkably similar to the ones the mostly white teachers in my workshops in urban areas like New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles routinely asked me. Apparently, they mattered here in Wyoming as well.

I had done my best to address the teachers’ questions carefully and consider their evident frustrations. In an effort to not offend, I steered clear of the elephant in the room—that is, the very obvious racial and ethnic differences between these mostly white teachers and their mostly Indigenous American students. Instead I shared a number of teaching strategies that I knew from experience worked for all students. I mentioned hands-on activities and guided inquiry in science, real-life applications and modeling in mathematics, and ways to incorporate writing across the curriculum. As I shared these strategies, I felt like I was connecting with the teachers. I had given them new information and helped them to approach their classes differently. After the lecture, many thanked me for my words and suggestions. A few even asked for links to articles so that they could learn more. That’s usually a good sign. I was content that the lecture had gone well, and I reveled in that feeling as I left to embark on the next phase of my trip.

But now, traveling through the Wyoming landscape, it struck me that although the teachers had gained insight about their profession, it wouldn’t be much help to them if they didn’t fully understand their students. I had given them tools to pacify their concerns, but nothing to truly get to the root of their problems. After all was said and done, I wasn’t sure that the teachers knew or cared about the origin of their challenges: the vast divide that existed between the traditional schools in which they taught and the unique culture of their students.

That afternoon, I was reminded of the book My People the Sioux by Indigenous American writer Luther Standing Bear. In this book, which was published in 1928, Standing Bear describes the beauty of the Sioux territory, the very land I was now traveling through. Long before I visited Wyoming, sitting on a park bench in the Bronx, Standing Bear’s words had both physically and intellectually transported me to this place. When I read his book, I saw in my mind the physical landscape that now surrounded me. The skies, the sun, and the clouds felt familiar. More importantly, his illuminating words enabled me to draw connections between the teaching and learning of populations like Indigenous Americans and the urban youth of color in my hometown.

Lessons from the Sioux

With the rumbling of a New York City commuter train above, and the Bronx skyline before me, I read Standing Bear and became fascinated with the ways of the Sioux. His stories of Native American life and the unique traditions of his people reminded me of my youth in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, and in the Bronx. As he described the distinct codes and rules of engagement of his people, I saw analogous images from the hip-hop generation. In one memorable passage he describes a solemn occasion commemorating a death, where a Sioux elder holds the bowl of a smoking pipe first to the heavens, then to the east, south, west, and north, and finally down, in the direction of Mother Earth. Reading this, all I could think of was the men in my urban neighborhood who lift liquor in brown paper bags to the heavens and to the earth in times of sorrow or to memorialize a member of the community. As a young man, I had always been fascinated by this lifting up and pouring of liquor “for the brothers who ain’t here” by older members of the community. At the time, I couldn’t identify why I was drawn to this practice, but I knew it signified something powerful. The meaning didn’t become clear until I read Standing Bear’s words about the role of elders, reverence for the land, and the powerful community practices around sorrow and healing. His descriptions of the Sioux opened up and deepened my understandings of life in the Bronx.

In his book, Luther Standing Bear poignantly describes his experience as a student at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School—the first institution designed to “educate the Indian.” Established in 1879 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the school was founded by Richard Henry Pratt, a US Army officer who had served in the Indian Wars and believed that his experience with the Native peoples he had formerly captured and imprisoned equipped him to educate them. The white teachers he recruited sincerely believed in Pratt’s vision. For them, it was because of Pratt’s genuine concern for the Indigenous Americans that he had found it in his heart to give them a better life through education. It was this idealism that led educators to leave positions at other schools to be a part of the experiment to “tame the Wild Indian.”

The Carlisle School employed a militaristic approach to “helping” the Indigenous Americans assimilate to white norms. For students, the authoritarian “care” that was shown to them at school stripped them of their culture and traditions, considered primitive and inferior. Unfortunately, because many of these students were far from the support of their Native communities, they were forced to assimilate to the culture of the teachers and the school so as to avoid the harsh punishments that would otherwise be levied on them. As the teachers worked to “tame and train” students who were described as “savage beasts,” students struggled to maintain their authenticity amid the efforts to make them “as close to the White man as possible.” This tension between educators who saw themselves as kindhearted people who were doing right by the less fortunate, and students who struggled to maintain their culture and identity while being forced to be the type of student their teachers envisioned, played a part in the eventual recognition that the Carlisle School was a failed experiment.

The teachers who were recruited to the Carlisle School were in many ways like white folks who teach in the hood today. Written accounts from that era confirm that Carlisle teachers saw themselves as caring professionals, even though students described many of them as overly strict and mean-spirited disciplinarians. One teacher wrote in the school paper, The Red Man, that the students had “unevenly developed characters, strong idiosyncrasies and a lack of systematic home training.” His only praise for the indigenous students was their “native unconscious keenness.” Another teacher described a teaching culture in which “the students are under constant discipline from which there is no appeal.” This culture of unrelenting discipline was presented by educators as benefiting the Carlisle School’s challenging population. The Carlisle system had a goal to “make students better,” but this goal was predicated on the teachers’ understanding that the students came to the school lacking in socialization, intellect, and worth. The school celebrated teachers’ rigidity and strictness out of a belief that this was the type of training that would be successful in acculturating indigenous students to white society.

The use of strong discipline with respect to “challenging” youth continues to be celebrated today, as illustrated by a highly publicized video in April 2015, during the protests that erupted in Baltimore, Maryland, in response to the death of a young black man while in police custody. In the video, the child’s mother is recorded beating and cursing at her son for taking part in the protest. While it is obvious from the recording that the mother was concerned for her child and maybe even feared for his safety, she showed this concern by berating him in public. The media praised the “riot mom” for how she addressed the situation—she was widely hailed as “Mother of the Year”—but in so doing perpetuated the narrative of young black boys requiring a tough hand to keep them in line.

Consider a teacher who graduates from a teacher-preparation program and has job prospects at both an affluent suburban school and what can be described as a poor urban school. Before the teacher can consider the two jobs, she must reckon with certain criteria beyond content knowledge, academic credentials, and teaching experience. In the more affluent schools, one’s ability to teach the subject material is prioritized, and so is a caring temperament. In this case, care is demonstrated by a teacher’s patience and dedication to teaching. In urban communities that are populated by youth of color, there are other, and oftentimes unwritten, expectations like having strong classroom-management skills and not being a pushover. In this case, care is expressed through “tough love.”

In my role as a teacher-educator, I often give an assignment to aspiring teachers that includes writing an autobiography and teaching statement to explore what brought them to the field of education. For those who go on to work in urban schools, I am always fascinated by the ways that these teachers’ descriptions of themselves and their craft highlight their concern for urban youth, empathy for their living conditions, and a desire to help them have more opportunities. As I watch them transition from aspiring teachers to practitioners, I see how this “care for the other” couples with expectations of managing and disciplining students, and the ways that they unintentionally become modern incarnations of the instructors at the Carlisle School through a tough-love approach to pedagogy. As I follow these teachers into classrooms and study the ways they interact with their students, I find that the students’ descriptions of their schools and teachers are similar to the ways that Indigenous Americans at Carlisle described their schooling experiences. Many urban youth of color describe oppressive places that have a primary goal of imposing rules and maintaining control. Urban youth in contemporary America use language similar to Carlisle students like Standing Bear and student turned teacher Zitkala-Sa, who highlighted the ways that the school disrespected the students and their home cultures. These students’ words stand in sharp contrast to those of their teachers as expressed in autobiographies and teaching philosophies.

The ideology of the Carlisle School is alive and well in contemporary urban school policies. These include zero tolerance and lockdown procedures. A student in a school I recently visited described the innocuous term school safety as a “nice-sounding code word for treating you like you’re in jail or something.” In urban school districts across the country, school safety personnel are uniformed officers who are part of the police force and often engage in discriminatory practices that reflect those in the larger community.

Like teachers who were drawn to the Carlisle School, white teachers are recruited to work in poor communities of color through programs like Teach for America, which tout their exclusivity and draw teachers from privileged cultural and educational backgrounds to teach in the hood. These programs attract teachers to urban and rural schools by emphasizing the poor resources and low socioeconomic status of these schools rather than the assets of the community. Adages like “No child should be left back from a quality education” and “Be something bigger than yourself” draw well-intentioned teachers desiring to save poor kids from their despairing circumstances. This is not a critique of Teach for America per se—as it serves a need in urban and rural communities. However, it and programs like it tend to exoticize the schools they serve and downplay the assets and strengths of the communities they are seeking to improve. I argue that if aspiring teachers from these programs were challenged to teach with an acknowledgment of, and respect for, the local knowledge of urban communities, and were made aware of how the models for teaching and recruitment they are a part of reinforce a tradition that does not do right by students, they could be strong assets for urban communities. However, because of their unwillingness to challenge the traditions and structures from which they were borne, efforts that recruit teachers for urban schools ensure that Carlisle-type practices continue to exist.

A fundamental step in this challenging of structures is to think about new ways for all education stakeholders—particularly those who are not from the communities in which they teach—to engage with urban youth of color. What new lenses or frameworks can we use to bring white folks who teach in the hood to consider that urban education is more complex than saving students and being a hero? I suggest a way forward by making deep connections between the indigenous and urban youth of color.

Connecting the Indigenous and Neoindigenous

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples defines the indigenous as people whose existence in a certain geographic location predates the region’s conquering or occupation by a colonial or imperialist power, and who see themselves as, or have been positioned as, separate from those who are politically or socially in command of the region. This definition, while it glosses over the nuances of what it means to be indigenous, nevertheless provides an outline and lays out the criteria for understanding who is and who isn’t indigenous. It touches upon indigenous peoples’ close ties to their land, their physical and mental colonization, and their position as distinct from those who govern them. It posits that the indigenous have their own unique ways of constructing knowledge, utilize distinct modes of communication in their interactions with one another, and hold cultural understandings that vary from the established norm. Above all, the UN definition of the indigenous speaks to the collective oppression that a population experiences at the hands of a more powerful and dominant group.

When we think of the Indigenous American students of the Carlisle School, the UN definition fits perfectly. However, when this definition is stripped of its explicit association with geographic locations, it’s clear that it can be applied to marginalized populations generally. Because of the similarities in experience between the indigenous and urban youth of color, I identify urban youth as neoindigenous. This connection between the indigenous and neoindigenous follows from what Benedict Anderson, professor of International Studies at Cornell University, describes as imagined communities that transcend place and time, and connect groups of people based on their shared experiences.

I first articulated the need for positioning urban youth as neoindigenous in a paper written for the American Association for the Advancement of Curriculum Studies in 2005. Since then, I’ve heard the term used loosely by academics in reference to the direct ancestors of those traditionally referred to as indigenous and also to a very specific Asian worldview. While multiple interpretations of what it means to be neoindigenous have value for understanding contemporary forms of oppression and expression, identifying contemporary indigenous as neoindigenous merely effects a renaming. For example, Aboriginal Australians have inhabited that continent for some fifty thousand years. Recasting contemporary Aboriginal Australians as neoindigenous extracts them from their history and attempts to restart it. On the other hand, positioning urban marginalized youth as neoindigenous moves beyond a literal biological or geographical connection and into more complex connections among the oppressed that call forth a particular way of looking at the world. Identifying urban youth of color as neoindigenous allows us to understand the oppression these youth experience, the spaces they inhabit, and the ways these phenomena affect what happens in social settings like traditional classrooms. It seeks to position these youth in a larger context of marginalization, displacement, and diaspora.

Like the indigenous, the neoindigenous are a group that will not fade into oblivion despite attempts to rename or relocate them. The term neoindigenous carries the rich histories of indigenous groups, acknowledges powerful connections among populations that have dealt with being silenced, and signals the need to examine the ways that institutions replicate colonial processes. The neoindigenous will continue to exist, and need to be acknowledged, in classrooms for as long as traditional teaching promotes an imaginary white middle-class ideal. As long as white middle-class teachers are recruited to schools occupied by urban youth of color, without any consideration of how they affirm and reestablish power dynamics that silence students, issues that plague urban education (like achievement gaps, suspension rates, and high teacher turnover) will persist.

The neoindigenous often look, act, and engage in the classroom in ways that are inconsistent with traditional school norms. Like the indigenous, they are viewed as intellectually and academically deficient to their counterparts from other racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. Too often, when these students speak or interact in the classroom in ways that teachers are uncomfortable with, they are categorized as troubled students, or diagnosed with disorders like ADD (attention deficit disorder) and ODD (oppositional defiant disorder). The Association for Psychological Science recently shared a study finding that black students were more likely to be labeled as troublemakers by their teachers and treated harshly in classrooms. Students who are treated harshly in classrooms are less likely to academically engage in classrooms, which results in their being perceived as academically inferior. For teachers to acknowledge that the ways they perceive, group, and diagnose students has a dramatic impact on student outcomes, moves them toward reconciling the cultural differences they have with students, a significant step toward changing the way educators engage with urban youth of color. Addressing the cultural differences between teachers and students requires what educational researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings describes as culturally relevant pedagogy. This approach to teaching advocates for a consideration of the culture of the students in determining the ways in which they are taught. Unfortunately, this approach cannot be implemented unless teachers broaden their scope beyond traditional classroom teaching.

Cultural artifacts like clothing, music, or speech are aspects of indigenous culture that are generally not considered by teachers to be related to education, but are one of the first things a teacher identifies when interacting with neoindigenous students. The wrong clothing or speech will get neoindigenous students labeled as unwilling to learn and directly impact their academic lives much in the way that it affects the indigenous. For example, if one were to ask the average person in the United States, Australia, or New Zealand to describe the indigenous peoples in their respective countries, the responses would probably be very similar, and include exoticized references to scanty clothing, “odd” living arrangements, “strange” speech, “weird” customs, and “primitive” art and music.

Educational anthropologist Rosemary Henze, in her work with Kathryn Davis, describes the indigenous languages of Australia and New Zealand as having much complexity and nuance despite the fact that they are generally perceived as substandard in the countries where they are spoken.8 In much the same way, educators perceive neoindigenous Spanglish (a mixing of Spanish and English) or patois as substandard. On a number of occasions, I’ve heard teachers mock neoindigenous slang in front of students, even while they themselves attempt to use it in an effort to look cool or gain “street cred” in other settings. A white female urban schoolteacher from an affluent background once told me that whenever she gets together with her friends, they say she’s “been in the ghetto with the black kids for too long” because of her frequent use of “street slang.” She giggled as she admitted that she sometimes “uses the kids’ phrases on purpose” to get a reaction from her friends. This teacher, like many of her peers, exoticizes neoindigenous language, but still holds a general perception that it represents lowbrow antiacademic culture. Ironically, when teachers try to use neoindigenous language, they often find it challenging to do so properly. They fail to recognize the highly complex linguistic codes and rules one must know before being able to speak it with fluency—that is, in a way that teachers view as substandard! I make this point to stress that the brilliance of neoindigenous youth cannot be appreciated by educators who are conditioned to perceive anything outside their own ways of knowing and being as not having value. This is similar to white teachers at the Carlisle School who sought to ban the language and customs of their indigenous students and replace them with “American culture.” The University of Minnesota Human Rights Center describes this process as the silencing of voice and history that is part of the indigenous experience. I argue that enduring this silencing process is something that both the indigenous and neoindigenous have in common, and should be used as a way to connect them.

Though there are obvious historical differences between the neoindigenous and the indigenous, it is important to recognize that urban youth are working within what Maori indigenous professor Manuhuia Barcham describes as the “politics of indigeneity,” which reinforces power structures that privilege certain voices while silencing and attempting to erase the history and value of others.

Consider, for example, the denial of the genocide of Aboriginal Australians by former prime minister John Howard despite reports and testimonials that confirmed the horrors they endured. This same denial exists today with neoindigenous populations who are pushed out of schools and into prisons and who can clearly articulate the personal devaluation they undergo in urban public schools. On a recent visit to a prison where I was speaking to young men of color who had been incarcerated for anywhere from two to twenty years, I struck up a conversation with a group of young men who described a number of incidents in their respective public schools that caused them to doubt whether or not school was for them. One story in particular resonated with me because of how similar it was to conversations I’ve had with other former urban public school students who have spent their lives doubting their own intelligence and making life decisions about what they can or cannot do based on something a teacher told them. This young man shared with me his experience in middle school, when a science teacher told him he was wasting his time going to school because all he would be when he got older was a gangbanger. He described this event and the older white male teacher in such detail, it was clear he had carried the incident with him for decades. I’ve heard versions of this story in rap songs, classrooms, prisons, and homeless shelters countless times. Despite its prominence, however, it is not part of the existent discourse on urban teaching and learning. When I mention it in academic circles, I am always challenged to think about it as the exception and not the norm. This denial of my reality in academic spaces signals more than individual denials of others’ histories; it is a systemic denial within institutions built upon white cultural traditions that oppress and silence the indigenous and the neoindigenous.

When the indigenous and neoindigenous are silenced, they tend to respond to the denial of their voices by showcasing their culture in vivid, visceral, and transgressive ways. For Aboriginal populations, thecorroboree is an event that transforms contemporary contexts via costume, music, dance, and ritual enactments. These celebrations enable participants to make a powerful political statement about how they are positioned in society and the importance of reclaiming their voices. These expressions of self are framed as entertainment or spectacles to be observed by tourists, as well as members of the dominant culture. As such they are an embodiment of what it means to be indigenous.

Like the indigenous, urban youth distinguish themselves from the larger culture through their dress, their music, their creativity in nonacademic endeavors, and their artistic output. In much public discourse, the ways in which they express themselves creatively are denigrated. For example, as a form of neoindigenous music, hip-hop is often dismissed by traditional cultural critics as “vulgar.” The innovation and technical skill required to create and perform this music is secondary to its “message,” which is often seen as threatening to mainstream culture and out of step with its values. Indeed, record companies deemphasize the music’s “message” to white audiences, while pushing the dance moves and style of dress of hip-hop artists to market this music.

Like the indigenous, who have been relegated to certain geographic areas with little resources but still find a way to maintain their traditions, the neoindigenous in urban areas have developed ways to live within socioeconomically disadvantaged spaces while maintaining their dignity and identity. They are blamed for achievement gaps, neighborhood crime, and high incarceration rates, while the system that perpetuates these issues remains unchallenged. In urban schools, where the neoindigenous are taught to be docile and complicit in their own miseducation and then celebrated for being everything but who they are, they learn quickly that they are expected to divorce themselves from their culture in order to be academically successful. For many youth, this process involves the loss of their dignity and a shattering of their personhood. Urban youth who enter schools seeing themselves as smart and capable are confronted by curriculum that is blind to their realities and school rules that seek to erase their culture. These youth, because they do not have the space/ opportunity to showcase their worth on their own terms in schools, are only visible when they enact very specific behaviors. This usually means they have the focus of the teacher only when they are being loud and verbal (often read by educators as disruptive), or silent and compliant (often read by educators as well behaved). Educators are trained to perceive any expression of neoindigenous culture (which is often descriptive and verbal) as inherently negative and will only view the students positively when they learn to express their intelligence in ways that do not reflect their neoindigeneity. Students quickly receive the message that they can only be smart when they are not who they are. This, in many ways, is classroom colonialism; and it can only be addressed through a very different approach to teaching and learning.

I do not engage in the work of connecting indigenous and neoindigenous either to trivialize the indigenous experience or exaggerate that of the neoindigenous. My point is to identify and acknowledge the collective oppression both groups experience and the shared space they inhabit as a result of their authentic selves being deemed invisible. Indeed, customs of the Maori in New Zealand vary as much from those of Indigenous Americans as urban youth from Los Angeles differ from their counterparts in New York City. However, their similarities are glowingly apparent if we choose to focus on them, and they offer a powerful new framework for urban education. The indigenous and neoindigenous are groups that have been victimized by different forms of the same oppression. The Bronx, New York, has no privilege over Gary, Indiana, just as Aboriginal voices have no value over the African indigenous. George Dei and Alireza Asgharzadeh, who have done powerful research on indigenous knowledge and postcolonial thought, argue that oppression “differentiates individuals and communities from one another” but “at the same time connects them to each other through the experience of being oppressed, marginalized, and colonized.” This is the reason I connect the indigenous and neoindigenous.

Indigenous and diasporic scholars have consistently argued that the ways we view those we consider “indigenous” must move beyond prescribed definitions issuing from colonial and imperial constructs and toward a more inclusive definition that considers how people categorize themselves based on their shared experiences with imperialism and colonialism in their varied forms. This definition allows us to see how the indigenous exist across diverse places yet remain connected. For example, the Aboriginal, the Maori, and the Indigenous American experience colonization and/or imperialism in different ways across different contexts but each group underperforms when compared to their white counterparts. These same achievement gaps exist between neoindigenous urban youth of color and their counterparts from majority-white schools with students of middle to high socioeconomic status.

Given the extended analogies between the indigenous and neoindigenous described above, and the ways that I have both experientially and theoretically showcased the connections between the two, it is clear that many teachers in urban schools today share the misguided, though caring, impulse that maintained poor schooling at the Carlisle School. The work for white folks who teach in urban schools, then, is to unpack their privileges and excavate the institutional, societal, and personal histories they bring with them when they come to the hood.

In this work, the term white folks is an obvious racial classification, but it also identifies a group that is associated with power and the use of power to disempower others. My use of the term white folks draws from the short story collection The Ways of White Folks, by Langston Hughes. These stories revolve around interactions between white and black people that can only be described as unfortunate cultural clashes. These clashes occur when the world of one group does not seamlessly merge with that of another group because of a fundamental difference in the ways they are positioned in the world. In each story, the black characters interact with white characters, ranging from the innocuous to the outrightly racist, with negative outcomes for the black characters. Hughes was deliberate in not painting all white people with a broad brush. He even has one of his characters mention “the ways of white folks, I mean some white folks.” Despite this effort, Hughes constructs a context where the societally sanctioned power that white people have over black people results in drama, and some humor, but overall outcomes that are largely unfavorable for the black characters.

Drawing from Hughes’s framing, I am not painting all white teachers as being the same. In fact, there are some people of color who engage in what Hughes would call “the ways of white folks.” However, there are power dynamics, personal histories, and cultural clashes stemming from whiteness and all it encompasses that work against young people of color in traditional urban classrooms. This book highlights them, provides a framework for looking at them, and offers ways to address them in the course of improving the education of urban youth of color.

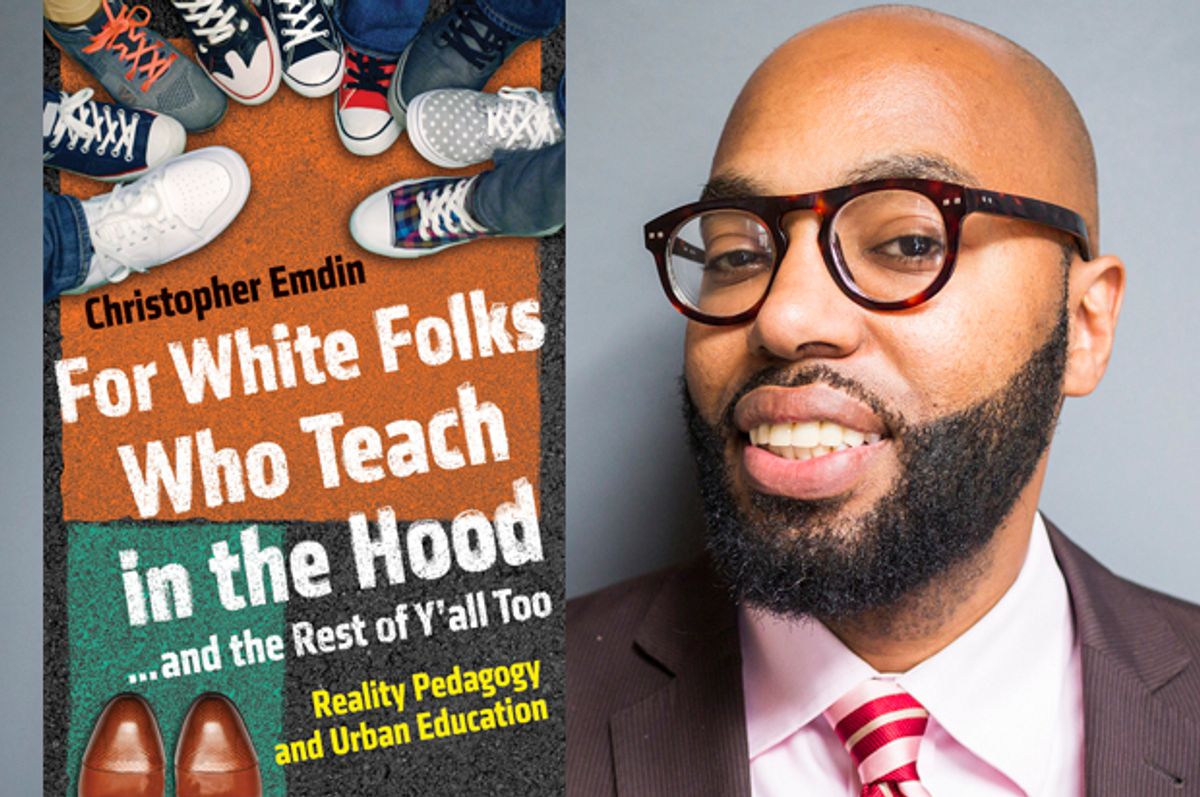

Excerpted from "For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and the Rest of Y’all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education" by Christopher Emdin (Beacon Press, 2016). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Shares