The path to marriage equality did not begin, of course, with Evan Wolfson's Harvard Law School paper. The very fact that Wolfson could conceive of such a paper was itself testament to the efforts of countless gay and lesbian advocates before him, operating in far more difficult circumstances.

A good place to start in assessing the prehistory of the marriage equality movement is the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay organizations in the United States. Founded in Los Angeles in 1950, the Mattachine Society ultimately included chapters around the country, and in the 1950s and 1960s was the nation’s leading gay organization. It took its name from masked critics of ruling monarchs in medieval France. At its inception, the very idea of a gay organization was so radical that the group met only in secret.

The Mattachine Society’s most illustrious member was Frank Kameny, a Harvard-educated astronomer who was fired by the US Army Map Office in 1957 when an FBI investigation revealed that he was gay. Kameny appealed his firing all the way to the Supreme Court, without success. But the experience prompted him to become one of the nation’s first openly gay activists. He founded the Washington, DC, chapter of the Mattachine Society in 1960, and also launched a systematic attack on the federal government’s discrimination against gay and lesbian employees. Notwithstanding his lack of legal training, Kameny operated as a “lawyer without portfolio,” assisting hundreds of employees in administrative appeals of their dismissals and shepherding their cases through the courts. With the support of the ACLU, he won his first victory in 1965, when the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit reversed the Civil Service Commission’s disqualification of Bruce Scott from the civil service on grounds of “immoral conduct.” In 1975, after many more battles with Kameny, the Civil Service Commission reversed its policy of categorically disqualifying gay and lesbian applicants. Kameny also took on the Defense Department for denying security clearances to gays and lesbians, and in 1975 it, too, abandoned that practice.

The first challenge Kameny and the Mattachine Society faced was simply to be free to associate as gay men. Sodomy statutes made intimate relations between same-sex couples a crime. Psychiatrists considered homosexuality a mental illness. Admitting publicly that one was gay or lesbian could result in ridicule, harassment, assault, isolation from one’s family, the loss of a job, or worse. Most gays and lesbians understandably chose to keep their sexual orientation hidden.

The invisibility of the “closet” made mobilizing for lesbian and gay rights all but impossible. Thus, the first strategic step toward achieving equality was, as gay rights scholar and advocate Bill Eskridge has called it, a “politics of protection.” The aim was to create space for gays and lesbians to come together without fear of official harassment. Gay and lesbian community centers, bars, and bathhouses all served this function. The Stonewall riots of 1969, in which gay patrons at a Greenwich Village bar turned on police and collectively asserted their right to be out, gay, and together in a public place, were the most dramatic and historic manifestation of this initial phase.

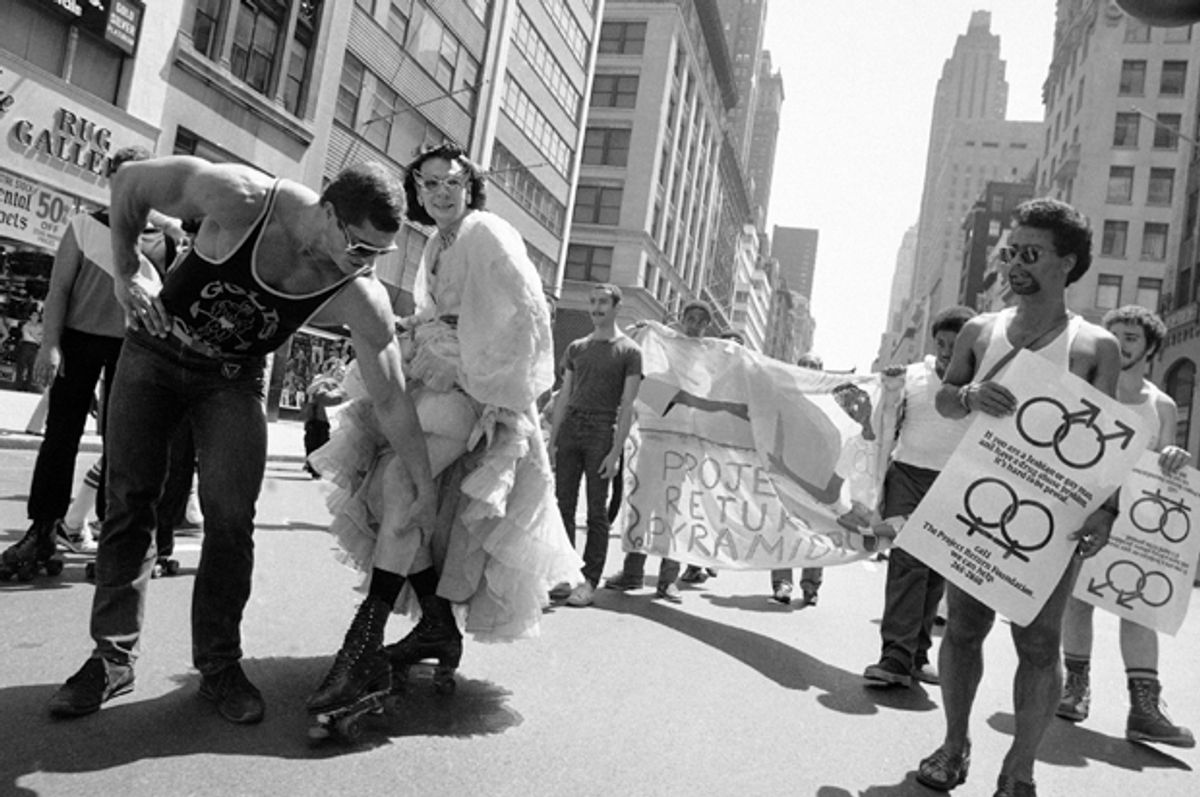

The next step was to make it safe—or at least, less costly—to “come out” by publicly identifying oneself as lesbian or gay. Gay rights groups fought for legal protections that would make it more likely that gay men and lesbians might feel sufficiently comfortable to identify themselves publicly. The ACLU Lesbian and Gay Rights Project, for example, invoked the First Amendment to protect the rights of students to form gay and lesbian student associations, first in colleges and later in high schools. And gay rights advocates argued for expanding anti-discrimination laws to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment, housing, and other fields.

In the 1980s, the AIDS crisis transformed the gay community. Many men were in effect outed by the disease itself as it afflicted them or their lovers. The life-or-death necessity for research and treatment spawned the creation of new advocacy organizations, such as Gay Men’s Health Crisis and ACT UP, as gay men and lesbians increasingly recognized the pressing need for nondiscriminatory health services, and came to understand that only through political organizing could they convince the government to invest sufficient resources in developing effective treatments. In a tragic but real sense, gay rights came out and of age during the AIDS crisis, as growing numbers of gays and lesbians proclaimed their sexual orientation publicly, joined political associations, and en- gaged in collective action to demand equal care and respect.

The AIDS crisis also set the stage for the fight for marriage equality. It urgently revealed the many problems that gay couples confronted when the states did not recognize their relationships. Gay employees whose partners were sick and dying could not get health insurance for them through their work. Gay men were denied visitation with their partners at hospitals because they had no officially sanctioned relation- ship with the patient. They often were not authorized to make end-of-life decisions for their partners. They faced difficulties dealing with funerals, estates, and the like, again because their relationships, even if longstanding, lacked formal status. The importance of “relationship recognition” became painfully evident, and the press ran many stories about the obstacles gay men faced as they navigated the ends of their partners’ lives.

When advocates began to address the myriad problems gay couples faced in dealing with AIDS, they did not at first demand marriage, still an unthinkable option. Instead, they requested lesser forms of domestic partnership recognition and benefits. They began by approaching sympathetic private corporations, universities, and cities. Over time the concept of same-sex domestic partnerships took hold in a wide range of private and public settings. The same pattern is evident with respect to legal protection from discrimination.

These developments, vitally important on their own terms, also contributed to making a marriage equality campaign possible. The care and support offered, and devastating losses suffered, by surviving partners became familiar to many straight Americans. As discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation was more widely prohibited, gay men and lesbians were more free to come out. It became increasingly common for straight people to learn that a family member, friend, colleague, or acquaintance was gay or lesbian—and deeply human and vulnerable. That knowledge in turn made it less likely that straight people would demonize, and more likely that they would empathize with, gay men and lesbians.

Some of the most important early gay rights advocacy focused not on legal and political change but on cultural transformation. In the midst of the AIDS crisis, gay activists founded Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, now known simply as GLAAD. Their mission was to promote accurate and positive portrayals of gay men and lesbians in the news and entertainment media. Among other accomplishments, GLAAD helped persuade CBS’s 60 Minutes to suspend commentator Andy Rooney for three months without pay when he made homophobic remarks on air. It blocked a planned television show to be hosted by Dr. Laura Schlesinger, a radio talk show host who had described homosexuality as a “biological mistake.” GLAAD also encouraged comedian Ellen DeGeneres to have the character she played on her television show, Ellen, come out as lesbian, and helped to convince the news media to shift their terminology from “homosexual” to “gay and lesbian,” and from “sexual preference” to “sexual orientation.”

There is no precise way to measure the effects of these wide-ranging efforts. But nearly all of the advocates, lawyers, and activists with whom I spoke agreed that each of the developments summarized here provided an important foundation for the marriage equality campaign. They helped make it possible for Evan Wolfson to write his law school paper, and for the many initiatives that would be necessary, inside and outside of courts, before the right to marriage equality that Wolfson envisioned could be realized.

Excerpted with permission from "Engines of Liberty: The Power of Citizen Activists to Make Constitutional Law," by David Cole. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2016.

Shares