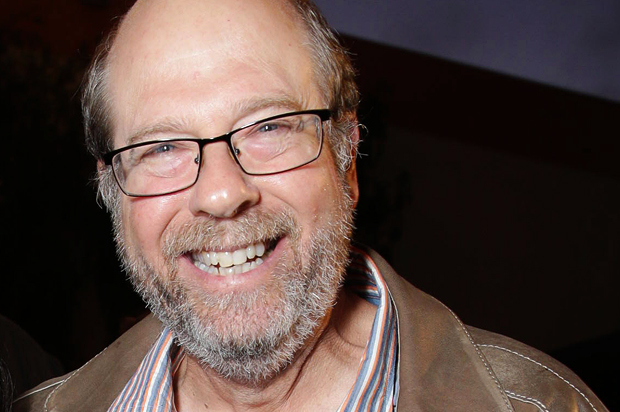

Stephen Tobolowsky has been a character actor since, he claims, “the Pliocene era.” The tall, balding, Texas-born performer has played doctors, teachers, geniuses, plumbers, priests and Rabbis, among numerous other “professional” roles in nearly 250 film and television shows. He is most recognized as Ned Ryerson, the life insurance salesman in “Groundhog Day,” but has also had memorable parts in shows like “Californication.”

In 2008, the actor started a podcast, “The Tobolowsky Files,” and in 2012, he published his fantastic memoir, “The Dangerous Animals Club,” which is both side-splittingly funny—he gets fired from a job in children’s theatre after saying the absolutely wrong thing to a young girl in Spanish—and also achingly poignant.

Tobolowsky’s remarkable storytelling abilities are in evidence in the new DVD “The Primary Instinct,” a performance film where he recounts episodes from his life. He describes notable anecdotes from his career, such as one that involves swimming in a vat of Bavarian cream and discovering that the substance has the reverse gravitational effect of water (i.e., it never leaves your orifices and crevices). He recounts memories of his family, including an unexpected autograph session with the 1960 Green Bay Packers, and his mother’s frequent and misguided use of a salty Ben Franklin quote as a way of grappling with heartbreak. But mostly, Tobolowsky provides the elegance and beauty of storytelling; how the true tales he spins reflect the surprises of life and the meaning of life.

“Tobo” as he is known, chatted via Skype with Salon about storytelling and his career. His interview was funny, surprising, and often quite profound.

Let’s start with a question you try to answer in “The Primary Instinct,” which is: Why do people tell stores? What made you become a storyteller?

The podcast dates back to my broken neck, which was 2008. [Tobo broke his neck in five places while horseback riding on the rim of an active volcano in Iceland.] The doctor told me I had a “fatal injury,” which isn’t something you should tell someone. So I thought: What if what he said was true? And with a broken neck, there’s not much you can do. So I thought: What if I started telling the stories for my children. They ended up in the podcast and in “Dangerous Animals Club.” I won the storytelling contest in sixth grade. I always enjoyed spinning a yarn. Only after the broken neck did I understand the power of telling true stories and not elaborating.

Yes! You repeat the phrase, “Truth trumps clever” in “The Primary Instinct” How did you determine this?

It gradually came upon me. I noticed the benefits of telling the truth: You don’t fill in the blanks of other people’s intentions. It can color the story, and make it bitter or overly optimistic. When you tell a true story, the story can continue after you tell it. Take for example, the story of my first job in summer stock. My college roommate and I drove to New York from Texas, and once we arrived, he realized he didn’t want to stay there. So he left me at the theater with my bags and went back to Texas. Why did he desert me like this? Why did he stick me in the mountains of New York with nothing? I was at his deathbed five years ago, and he was only conscious a few minutes at a time. And he told me, “Tobo, I wanted to tell you why I left you in the road in New York.” I asked, “Why, Jimmy, why?” He said, “My girlfriend was pregnant with someone else’s child and she was alone. I went back to take care of her, and I couldn’t tell anyone.” I didn’t color that story in, so the reader filled in the blanks. The truth knocked me in the solar plexus.

You describe your process of researching a role as “more detective than interpreter?” For example, in “The Confirmation,” you play a priest and take the confession of a young boy. How do you approach a character who has just one or two scenes in a film?

I start with simple questions: What is my greatest fear and what is my greatest hope? Answering those two questions will open the door to other questions. When in doubt, I start off with just facts. How long have I been a priest? Have I been a good priest? What is my congregation like? What are my expectations? I surround my world by what my expectations are. I can build the wrong expectations in so I can be surprised by the scene. Working on TV in “Californication” or “Silicon Valley,” which are very plot oriented arc-type stories, the writers are evolving the story. It’s not a beginning, middle, and end. They don’t know what’s next, and could pull something out of the hat that would make everything not true.

If the secret to telling a good joke is to tell it fast, what is the secret to telling a good story?

The problem I have when I see storytelling is that they tap dance with needless detail. As an audience, we are way ahead of that. I believe in Aristotelian concept of set up, rising action, and payoff. It’s nice if Act 1 and 3 connect. There are variations on that. But before I tell a story, I think what is that story about? As I write, I allow it to change. I start with the most important part of the story. I told stories about Beth [Henley, Tobo’s former girlfriend] and I coming to Los Angeles and our life together and our friends. But it’s important to know how Beth and I got together. I began in Act 2 went back to Act 1 and then wrote Act 3. So I knew what the payoffs are. And I don’t stick to an outline. I let the story inform me and then go back and cut and try to make it clearer. It’s important to know where you’re going. You may not know why.

I was surprised by how PG-rated your performance was. Are you secretly foul-mouthed and foul-minded?

Yes, [laughs] though not completely foul-mouthed. Sarah Silverman puts me to shame. We worked together a few times. She’s surprisingly sweet, but she can shock me. It all began when I had to do one of my first [storytelling] shows, and there, sitting in the 400-people auditorium, were all these 5 year-olds. And then, in the heart of the audience was a section of white hair and beards—grandparents! —so I thought, OK, we’ll go clean with this. And the audience was so relieved. They didn’t feel assaulted by language.

I had an accidental encounter with Harold Pinter once. I was directing “Miss Firecracker” and he had a play opening, and we were both at the bar, and had a couple of drinks. When he introduced himself, I went, “Holy Fuck!” He said he was a guy who said he never uses profanity in his plays because they are nuclear bombs. It affects the audience and the play. No one can hear anything beyond those words. I took him to heart. I am going to make sure in the podcasts and my books that if someone says it, I’ll quote them, but I won’t use it as a description. “Fuck” has more definitions than any word in English. It’s a noun, verb, adjective, etc. It has 135 meanings, which makes it meaningless, and using it makes you lazy.

You recount your surprise about being cast as “buttcrack plumber,” your misadventures with a cocksock and blue goo on the set of “The Lone Gunman,” (and the crew’s shrugging at your nudity), and being face down in a Pamela Adlon’s maxipad for 5-hours shooting “Californication.” You also discuss hosting not “orgies” but “nudist parties” at your Hollywood Hills home. What makes you comfortable in your own skin?

They were not nudist parties. It just happened that way. Guests would get naked and jump in the pool or have sex in the yard. I was a good host and brought them beer and wetnaps…. I did projects where I was naked, “Californication,” and I had heart surgery. What makes me comfortable now is telling the truth as much as I can, undo regrets I have had in the past, and avoid future regrets. Living with a regret is a waste of emotion, but the purpose of regret is instruction. And that’s the difference between regret and shame, which is condemnation. Regret, you feel bad, and don’t do anymore, but if you don’t listen to that… I regret that I didn’t catch a fly ball when I had the chance. You don’t have that many opportunities to catch a fly ball.

You talk about hope vs. fear and discuss a sense of self-preservation. Is this what accounts for your work ethic?

It was very much fear that drove me. I was afraid for my family; I have this mathematical equation in my head: A lot of us are happy—almost everyone I know sees our lives as a simple equation as a form of addition. Stephen + beer = great. Stephen + clean sheets = fantastic. It doesn’t work with world peace, or the cure for cancer. When you see subtraction, fear enters the picture. Things get smaller and smaller, and you lack the sensitivity to see the addition. There’s a beautiful line in George Eliot’s “Adam Bede.” His father has died and his mother is “sitting in the dreary sunshine.” That’s depression—the inability to see the sunshine. You get the contagion of seeing the subtraction in your life, which triggers the fear, and then you get more desperate. The other side of that is when you face the fear and get to the other side, and experience triumph. I think in a story, you want triumph. That doesn’t mean a happy ending but some kind of triumph.

Pessimists view losing as one of the downsides of life, and they try to protect themselves from loss. They take a cynical view that keeps them from experiencing the positive, the win. I think losing can be incredible blow, an L on the scorecard, but you can have this enormous triumph. When my relationship with Beth crashed and burned, it made me better and stronger.

You talk about your mother, who makes us laugh in her misquoting of Ben Franklin, or cry at the story about the pennies. How do you process what you have learned from her, and distill it into useful nuggets?

My brother and I had a long discussion about your question. One of the things we realized was that mom was always an innocent. She never had an agenda. She had a good heart and saw the world very simply. Throughout our life we might laugh at mom—the Ben Franklin quote is something a 10-year old would do—she didn’t see what he was saying. It was the innocence that made the things she said and did so pure, and like poetry. It was heartfelt, it wasn’t clever, it was never coy, it was always wise. I’m not saying that she was intelligent school-wise, but she was wise. She didn’t let her education get in the way of her wisdom.

What might folks be surprised to learn about you?

I keep being surprised by what I’m interested in. Lately, my wife and I have developed a fascination over honeybees. I don’t know why. We bought beekeeper suits. We’re going out in the desert in our bee suits and do a “honey-moon” and smoke the bees. I have no idea where it came from. Sometimes triggered by my wife, and sometimes by me. My broken neck said focus on finding the addition. You have to.

You make a comment that we use a mirror to look at ourselves, and philosophy to look at ourselves. Which is really profound. How do you see yourself?

The more I look at the cracks and crevices, I see a person who is fundamentally flawed. I have a limitless desire to succeed and be good and do the right thing. It makes me think I’m kind of like Adam. I’m flabbergasted at my weaknesses. I see them coming, and I’m like a car on an icy road—I can’t avoid it. I fall into trap after trap after trap.

In the Talmud, they have a series of boundaries about when it’s too late to say the Shima [nightly blessing]. It’s a commentary on boundaries. We can call them manners, or art, or scientific method. We fill our lives with these boundaries that protect us. I know this, and yet I still break the boundaries, and still fall off the cliff. That perplexes me and tortures me and fascinates me.

Is there a character you’ve always longed to play?

[Closes his eyes, thinks]. There are so many roles I long for. I’ve play stud-hosses, geniuses, holy men, doctors, street people… [thinks some more]. I’m about to do Jon Robin Baitz’ “Other Desert Cities.” I’m looking forward to that because that’s a role I’ve wanted to do. It’s a political man, which I am not. And it’s someone who is lost in thought through most of the play. I’ve never had a chance to do that. I would find it a challenge to play someone who loses a lot. I have such antipathy for it. I’d have to see if I would do it honestly, or turn it into an underdog story.