I grew up as a fan of the San Francisco Giants, which meant something very different then than it does now. In the 21st century, the Giants are an enormously rich and successful franchise whose fancy waterfront stadium and affluent, tech-economy fan base serve as a perfect illustration of the way baseball has been transformed — not to say gentrified, a loaded term that fits all too perfectly in this context. To say it wasn’t always that way is an understatement. None of this took place in a vacuum, to be sure: San Francisco was a frayed and downtrodden city for much of the 1970s and ‘80s and its baseball team reflected that. The Giants were perennial also-rans who struggled to draw fans to the wind-blown desolation of Candlestick Park, a concrete monstrosity that the city fathers had perversely located on an isolated peninsula in the city’s southeastern corner. We were repeated told that the team would be sold and moved to some more hospitable city: Toronto or Tampa or Las Vegas or damn near anywhere else.

Only the Giants’ road games were on TV (announced by the legendarily laconic Lon Simmons), and not too many of those. Seeing a game in person either involved navigating strangled traffic and tundra-like parking lots or a slow public-transit journey involving at least one transfer. I can remember going to a game against the Houston Astros with my friend Chris from down the street. We took a bus and then a train and then another bus. Whatever the tickets cost — the price that sticks in my head is $2.75 — I guess our allowances could handle it. We plotted the journey out with our parents, but we went on our own. (Maybe our dads understood what a dire experience it was likely to be.) We were 12 years old.

Was baseball in better shape, as a business or an industry or an entertainment product, when Chris and I could go to a game without adult chaperones, without buying tickets from StubHub weeks ahead of time, and without much advance planning? Or when, a few years later, I literally snuck into a World Series game at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore? (You gave a local kid a few bucks, and he showed you the hole he had cut through the cyclone fence.) Clearly not, and when culture-vulture types like me come along to proclaim that baseball is dying, its boosters have all kinds of impressive numbers at their disposal. But baseball was in a vastly different cultural position in those years, one that is difficult or impossible to quantify.

Chris and I and that kid with the wire-cutters in Baltimore came along toward the end of a long period in American history when baseball served as a kind of male-coded cultural glue (although it certainly entrapped some women and girls) that transcended race, religion, socioeconomic status and geography. We felt ourselves connected, with no sense of detachment and no quotation marks, to the mythic lore and overwrought symbolism of baseball. I probably knew, at that age, the anecdote recounted in the new baseball-boosting documentary “Fastball,” about how Walter Johnson, later a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Washington Senators, was discovered playing semi-pro ball in the Snake River Valley of rural Idaho. I doubt anyone plays semi-pro baseball in the Snake River Valley today (except on the Xbox), and if anyone does they definitely don’t include the next Walter Johnson.

Were we kidding ourselves, at the time, about the enduring cultural power of baseball, which was visibly fading in places like the frigid, empty bleachers of Candlestick Park? Is my backward glance at that era now tinged or occluded by middle-aged masculine nostalgia? Yes and yes. But certain things are not illusory, starting with the fact that what happened to baseball has more to do with the social segmentation, niche marketing and cultural commodification that characterize 21st-century America than with baseball itself.

Baseball has been reinvented, whether deliberately or accidentally, as an immensely successful niche sport whose audience is overwhelmingly white, suburban, affluent and middle-aged or older. It has pretty much become the Republican Party of professional sports. I mean that as a metaphor: In cities like Boston and San Francisco, baseball’s core demographic in the squaresville top tenth of the Caucasian population no doubt includes plenty of liberals (although I’m going to crawl out on a limb and say that they skew toward Clinton rather than Sanders). If this transformation doesn’t pose an economic and demographic problem at the moment, and apparently will not do so into the medium term, it’s hard to imagine that it’s sustainable indefinitely.

No, baseball isn’t dying, as ardent defenders like Maury Brown of Forbes constantly remind us. Whatever happened to the sport formerly known as America’s national pastime, “death” does not describe it. Major League Baseball was a $9.5 billion business in 2015, and has experienced at least a dozen years of steady revenue growth, right through the big financial crash of 2008. Some baseball insiders predict that MLB’s revenues will soon surpass those of the concussion-plagued National Football League, long the Goliath of American spectator sports. (The NFL grossed about $12 billion last year.)

Although baseball’s owners have made various attempts to contain player salaries over the years, with all that money flowing in they really haven’t needed to. At least 10 of the sport’s big-name stars will earn $25 million or more apiece in the 2016 season, which opens this weekend, led by Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Clayton Kershaw at $32 million. (Perhaps half the players on that list are being egregiously overpaid for past accomplishments, but that’s how it goes.) Even unsuccessful teams keep signing cable-TV deals involving remarkably large numbers. The Arizona Diamondbacks are feuding with local authorities over their decaying home stadium; they haven’t made the playoffs for five years and have played in the World Series only once, in 2001. Yet for reasons someone other than me will have to explain, Fox Sports Arizona just agreed to pay $1.5 billion to carry D-backs games for the next six years, replacing an old contract at one-sixth the price.

But there are lies, damned lies and statistics, as Mark Twain famously observed (wrongly attributing the quote to Benjamin Disraeli), and baseball’s obsessive relationship to statistics is one aspect of its cultural problem. No, I’m not being an old-line fan complaining about the rise of “sabermetric” measurements of player value, such as “on-base plus slugging” (OPS) or “wins above replacement” (WAR). Or at least not exactly. Those newfangled stats have sometimes led baseball fans and general managers hilariously astray, as with the brief mania for “three true outcome” players, meaning hitters who strike out, walk or hit home runs, but rarely do anything else. But they emerged more or less organically from the nerdy, monastic nature of baseball fandom as it encountered the Information Age, and they successfully quantified some of the sport’s esoteric mysteries, including the fact that a .290 hitter is sometimes superior to a .310 hitter and that certain old-school stats, like runs batted in (RBIs) or a pitcher’s wins and losses, are almost meaningless.

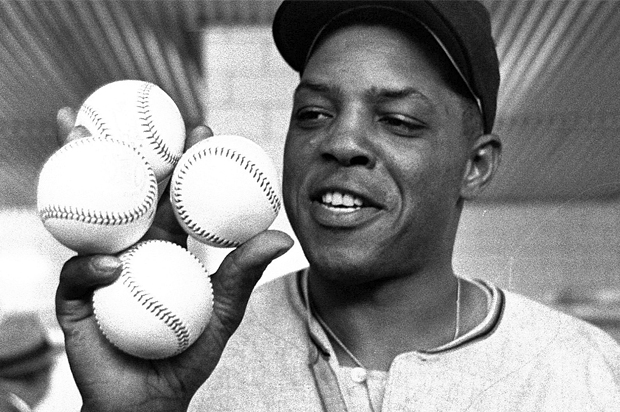

If the numbers tell us that baseball isn’t dead or dying, they cannot quite explain how and why it has so thoroughly driven away younger fans, working-class fans and nonwhite fans over the last three decades. Baseball is now largely a sport played by exurban white Americans and young men from the Dominican Republic and other Caribbean nations, with a smattering of imported Asian players. African-American participation in baseball is at or near an all-time low, a change that is glaringly obvious to those of us who grew up when most of the game’s best hitters were black Americans, from Willie Mays to Willie Stargell to Reggie Jackson to the steroid-tainted home run king, Barry Bonds. The 1979 Pittsburgh Pirates, who beat the Orioles in that World Series game where I snuck through the fence, featured eight black or Latino players among their starting nine.

Some baseball purists do blame the influence of sabermetrics for baseball’s altered and diminished cultural status, or blame the various innovations designed to modernize the sport or broaden its appeal. I don’t much like interleague play or video replay myself, or even the designated hitter (introduced when I was a small child). But at worst those things are symptoms of a deeper and broader ailment, not causes.

As I have suggested, the real meaning of the question “What happened to baseball?” is probably “What happened to America?” In an era of increasing political division and economic inequality, the naïve and sentimental democratic dream that baseball once appeared to represent has become unworkable and even embarrassing. If my friend Chris and I were 11 years old today, we might watch Giants games on our dads’ big-screen TVs once in a while. (Most likely while wearing our Stephen Curry or Lionel Messi replica jerseys.) But would we feel anything more than bafflement, impatience and contempt for the fatuous middle-aged notion that baseball somehow expressed the American soul — or that America had a soul?