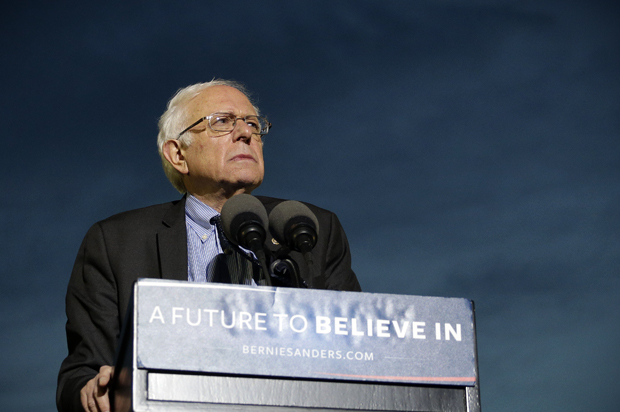

Early last week, leading figures in Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign hosted a conference call with political reporters to push the narrative that they still saw a tenuous “path to victory” over Hillary Clinton in the contest for the Democratic nomination. There was nothing so extraordinary in that: Losing candidates, like baseball teams who are 10 games back at the All-Star break, often claim they have a secret plan to win. (I’m looking at you, Marco Rubio.) It struck me, however, that this ritual exercise shone some light through the cloud of existential doubt enveloping the bizarre alternate universe of the 2016 campaign, and that it resembled the old Soviet-era joke about communism and capitalism: Everything the Sanders team had to say about their candidate’s strength was false; everything they said about their opponent’s weakness was true.

In the wake of Sanders’ big wins in the Alaska, Hawaii and Washington caucuses last weekend, campaign manager Jeff Weaver argued that the Vermont senator had recaptured the momentum and was on course to overcome Clinton’s large lead in pledged delegates. Strategist Tad Devine asserted that Clinton’s delegate advantage has been whittled down to about 240 (the Guardian’s published count currently puts it at 263). Factor in the hundreds of unelected party apparatchiks known as superdelegates, who overwhelmingly support Clinton, and her lead is closer to 700. Devine hinted that some superdelegates are beginning to wobble in the face of Sanders’ superior poll numbers against Donald Trump, but declined to provide specifics.

Clinton’s victories in several large states on March 15 — when she realized a net gain of 104 pledged delegates, 68 of them in Florida alone — struck most people in the political and media castes as tolling the final bell on Sanders’ realistic chances to win the nomination. But Bernie has been pronounced dead several times before and risen from the tomb, and Devine, a veteran Democratic operative who goes back to Jimmy Carter’s re-election campaign in 1980 (which can’t be a happy memory), has acquired the reputation of a necromancer in the occult operations of the 2016 campaign. So when he assured us that we had once again failed to perceive the true meaning of events, we listened attentively, suspending our disbelief as best we could.

Whether Devine’s fanciful campaign narrative — which he was handsomely paid to construct, let us remember — has any merit is not the part that interests me. But I suppose it’s worth spinning out a little. In his telling, March 15 will soon have a much different meaning, as the “high-water mark” of the Clinton campaign, the apex of her delegate lead and the turning point that preceded the last and most unlikely of Bernie Sanders’ unlikely comebacks. Here’s how the story goes: Clinton’s victories over Sanders almost don’t count, because they have largely come in states where Sanders lacked the resources and opportunity to compete with her on level terms. Where he’s had those things, he has done extremely well, and in the battleground states just ahead, her aura of inevitability will melt away like a papier-mâché tiger in the rain.

This hypothesis or prophetic vision or whatever it is has been much debated and dissected over the last few days. It’s fair to say that by the normal standards of political insider-baseball, its plausibility is near zero. Devine is blatantly cherry-picking favorable data and ignoring the other kind: The Sanders campaign sure looked like it was competing in Nevada and South Carolina and Massachusetts and Ohio and Illinois, and lost them all. (A different result in three of those five states, let’s say, and the entire complexion of the Democratic campaign is different today.) As Devine admitted during the call, Sanders would have to win most of the remaining states on the primary calendar to overtake Clinton, and essentially all the big ones. If he fails to win Wisconsin next week, and New York on April 19, and then Maryland and Pennsylvania a week after that, future conference calls of this type will become increasingly challenging, and may require a Santería priest and the sacrifice of live poultry.

But as I say, Devine’s patently absurd claims about what is likely to happen are not the important part. First of all, “likely to happen” and “patently absurd” have not proven to be useful standards this year, when the aforementioned norms of political discourse have collapsed. One reason the thought-leaders of media groupthink listened so eagerly to Devine’s Gandalfian pronouncements is that we’ve been wrong about damn near everything in 2016 — wrong about Sanders, wrong about Trump, wrong about the enduring power of the “Republican establishment” and wrong about the stability of the two-party system. Who is to say we’re not wrong this time too? Who can imagine what new frontiers of wrongness lie ahead?

But there’s more going on beneath the Democratic endgame than just widespread cognitive dissonance and epistemological uncertainty, although those are powerful forces that have turned American politics in 2016 into a delusional realm halfway between a dream state and a meth high. In all likelihood, Devine is doing what people like him always do: He’s playing out a losing hand to the best of his ability, he’s positioning himself for future employers and he’s pursuing a tactical short game aimed at the Clinton-Sanders peace treaty that lies in the not-too-distant future.

Devine is also a genuine convert to the Sanders revolution, and another reason we all listened to him was because he has gotten ahold of an important truth, or at least half of one. In the most quoted line of that conference call, he told us that Hillary Clinton remains the “clear frontrunner” but “has emerged as a weak frontrunner.” As an argument that Sanders might still defeat her, that’s pretty feeble; it sounds more than a little like doublespeak or poor-mouthing, like a football coach saying, heck, we’re the underdogs but we like it that way.

But Devine’s assessment of Clinton as a weakening frontrunner carried an irresistible resonance during a week when Clinton apparently accused a Greenpeace activist of being a Sanders operative for daring to mention her fund-raising ties to the fossil fuel industry, and by implication the larger question of who is funding her campaign and why. It was a week when her poll numbers continued to droop and her negatives continued to climb, a week when the background drip-drip-drip of suspicion around the email scandal refused to abate, and a week when Sanders reported another record-breaking month of small donations and drew a crowd of more than 18,000 people to a rally in the South Bronx. At a point in the cycle when leading candidates typically gain momentum, Clinton finds herself in the unusual position of holding an apparently insurmountable advantage even as her campaign begins to leak oil and emit strange clanking noises.

A weakening frontrunner is not necessarily destined to lose, and it remains more likely than not that Clinton will be the Democratic nominee and take the presidential oath of office next January. Of course I don’t want Donald Trump to be president, or at least I don’t think I do. (On the level of pure nihilistic malice, as expressed recently by Susan Sarandon, one can argue that might lead to more change, more quickly, than any other result.) But I’m going to suggest, for about the 75th time, that the outcome of the 2016 presidential election is not the only important political question of the moment, and probably isn’t the most important question. Hillary Clinton was never the fundamental problem, and Bernie Sanders almost certainly isn’t the solution, and the endgame of their primary confrontation isn’t going to settle anything.

If Democrats believe that Clinton’s likely nomination and election — presumably in a fall campaign against an incoherent sociopath — means that order has been restored to the political universe, and means that their party can march happily into the future, free of the chaos and darkness that has consumed the opposition party, they are deliberately ignoring the obvious. Milder mirror images of the internal contradictions and divisions found among Republicans can also be found among Democrats. It’s a striking and hilarious fact that both parties have arrived, via disparate routes, at probable nominees who are widely despised by the general public. If one of them is seen as far more loathsome than the other, that should hardly be seen as a glowing endorsement of the overall process.

The divisions that have surfaced this year among Democrats, or between the institutional Democratic Party and the resurgent nonpartisan left, are latent or immanent rather than ugly and unavoidable — at least for now. In the current campaign, those divisions have been papered over with forced and frayed politeness, or with the official fiction that Clinton and Sanders hold generally similar positions, although it has become increasingly clear that they represent different generations, different worldviews and profoundly different attitudes toward political and economic power.

Tad Devine’s Magic 8-ball wisdom won’t be enough to drive Bernie Sanders on to victory now. The most striking aspects of Sanders’ campaign are how close he came, how difficult he has been to stop and how much passion he has continued to generate long after the battle was lost. As Devine reminded us this week, the X factor in the Democratic race all along has not been Sanders but his opponent, who has had every possible advantage yet seems almost fiercely determined to lose. Hillary Clinton embodies all the Democratic Party’s contradictions in one person, having held every possible position on every possible issue at one time or another, to go with her various accents and uncomfortable personas. She is simultaneously the most powerful and most self-destructive of candidates; sometimes she looks like the HMS Victory of politics and sometimes she looks like the Titanic, loaded with albatrosses and towing the Hindenburg.

I can only see one scenario in which Sanders becomes the 2016 Democratic nominee: the total implosion or self-immolation or indictment of Hillary Clinton. Similarly, there is only one scenario in which Donald Trump is elected president. Unfortunately, it’s the same scenario. Sure, that would be a bizarre and outlandish turn of events, more like a plot twist on a bad TV show than reality. Have you been paying attention?