It’s harder to be shocked by Robert Mapplethorpe’s work than it used to be. Or rather, beside a few boldly provocative pieces – you know the ones -- that stirred up hatred and opposition during the culture wars of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, he now seems like a significant and domesticated mainstream artist. The two retrospectives of his work going up in Los Angeles and the documentary that aired on HBO last night, “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures,” show not only that he’s become part of the establishment, but that the controversy around his work seems to have faded out.

So what happened to Mapplethorpe in the years since Washington’s Corcoran Gallery of Art cancelled a show of his photography? Or, since the artist died of complications of AIDS in 1989, what’s happened to us? Are there people who still hate this work?

It’s more than just his appearance at the center of Patti Smith’s memoir, “Just Kids,” which paints him as a shy, striving innocent instead of the assertive pornographer that Jesse Helms and others once smeared him as. It’s partly, as one of the documentary’s sources, photography critic Philip Gefter, says in the film, gay liberation and the rise in photography’s prestige happened around the same time.

While Mapplethorpe’s images led Sen. Helms to describe the artist as “a known homosexual who died of AIDS,” these days his photographs sell for enormous sums, and even the most far-right politicians tend not to weigh in on visual art.

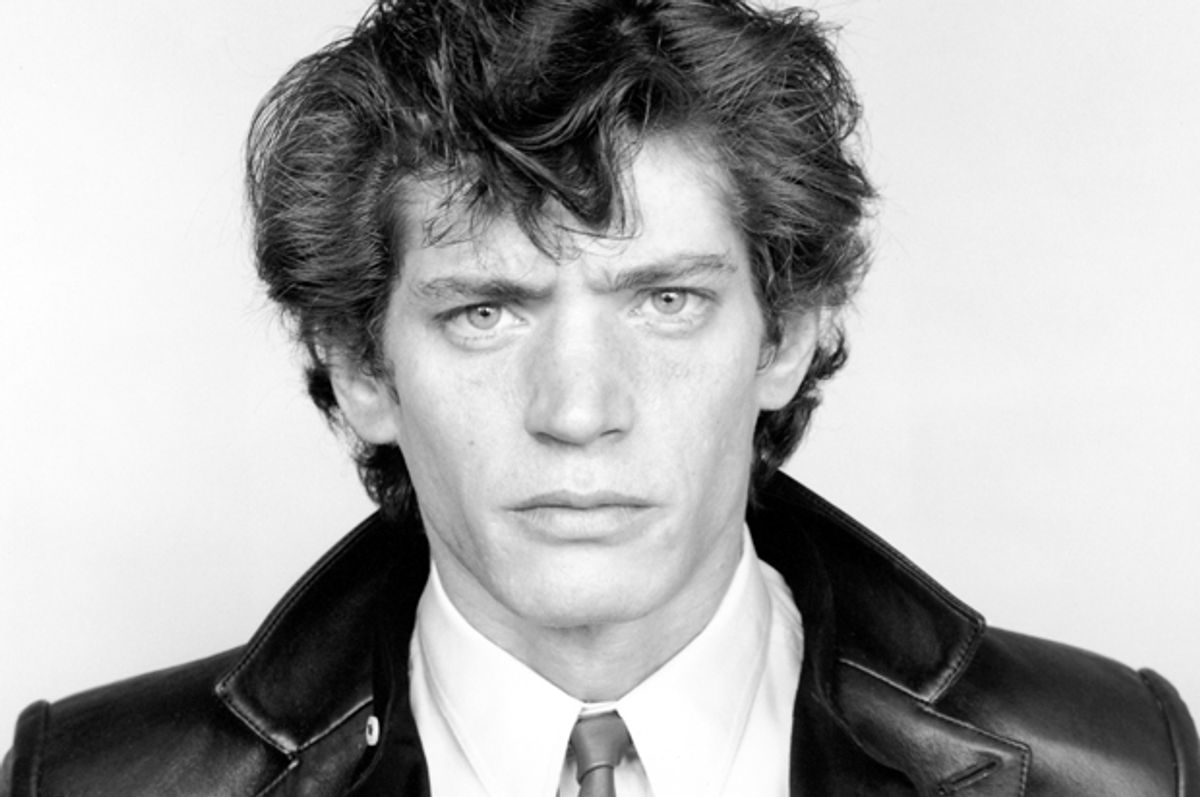

The film begins with the artist’s childhood in Queen, growing up in a pious Roman Catholic family headed by a father opposed to his son committing his life to art. Gangly and awkward, the young Mapplethorpe grew into a faun-like enigma who Fran Lebowitz described as “a kind of ruined Cupid.”

As the documentary moves along, figures like Patti Smith, the art dealer Sam Wagstaff, Debbie Harry, and others come and go in interviews and archival footage. We see all the phases of the artist’s career, from his early interest in formalism to his concentration on nude black men. The film ends at it begins, with Helms denouncing Mapplethorpe and the National Endowment for the Arts, which help fund the ill-fated Corcoran show with a $30,000 grant.

But it seems, decades later, mostly the story of any artist who struggled early on, grew artistically, and took a while to get recognized. The controversy may have taken a lot of out of the artist – and the larger culture war that involved Andres Serrano and Karen Finley and others created a lot of heat. But it ended up, in the end, fairly short-lived. No one will picket the Mapplethorpe exhibits this year.

The glib and reassuring conclusion would be to say that the culture wars are over and that the decades have led to more tolerance. Certainly, we don’t hear phrases like “known homosexual” quite as often.

But as Boston University religion professor Stephen Prothero wrote in his book, “Why Liberals Win the Culture Wars (Even When the Lose Elections),” we’ve just found other things to fight over – many of them more significant than museum shows.

Gun control, religious liberty, Black Lives Matter and funding for Planned Parenthood are all high-profile issues in the presidential campaign. Perhaps the most intense battle, though, is the one over immigration, which National Review’s Reihan Salam correctly identifies as a “fight over the future of American national identity in the face of rapid and accelerating demographic change.”

These days, the NEA avoids controversial work, putting much of its funding into audience development. The kinds of pornographic images that were once kept private – that seemed like revelations to a lot of people when Mapplethorpe riffed on them – circulate on the Internet. Vanity Fair ads flirt with nudity even as Playboy discontinues it. Gay celebrities are well established, with trans people now making up the cultural cutting edge. Mainstream comedians make sexually explicit jokes that millions of people watch on cable, where nudity is standard after 10 p.m.

Our culture has a very different relationship to sexuality and gender, especially their visual dimensions, than Mapplethorpe did when he was taking his photographs in the '70s and '80s. This doesn’t mean, culturally speaking, that everything is smoother now: Racially, the country is probably more on edge than it was back then, and there's more distrust.

But in the artist’s absence, the work has – oddly -- changed a lot as the world around it has altered. Disease brought the man down, tragically, but for all kinds of reasons, his art ending up winning.

Shares