In September of 1986, Maia Szalavitz was charged with felony possession – nearly 2.5 kilos – of cocaine and faced 15 years to life under New York’s unduly harsh Rockefeller drug laws. Before then, she was a student at Columbia University, but had been suspended for dealing. After getting kicked out of a school she had worked her whole life to get into, her cocaine use accelerated to the point where she was injecting up to 40 times a day, and eventually escalated to speedballs, a powerful mixture of cocaine and heroin in a single shot.

At 23, when the thought crossed her mind of sleeping with a man for drugs, she knew it was time to get help, and voluntarily entered treatment. After her drug charge was eventually dismissed, she built a career dedicated to understanding one of the most complex entanglements human beings endure: addiction. She has since gone on to write about drugs, policy, and science for nearly 30 years with remarkable consistency.

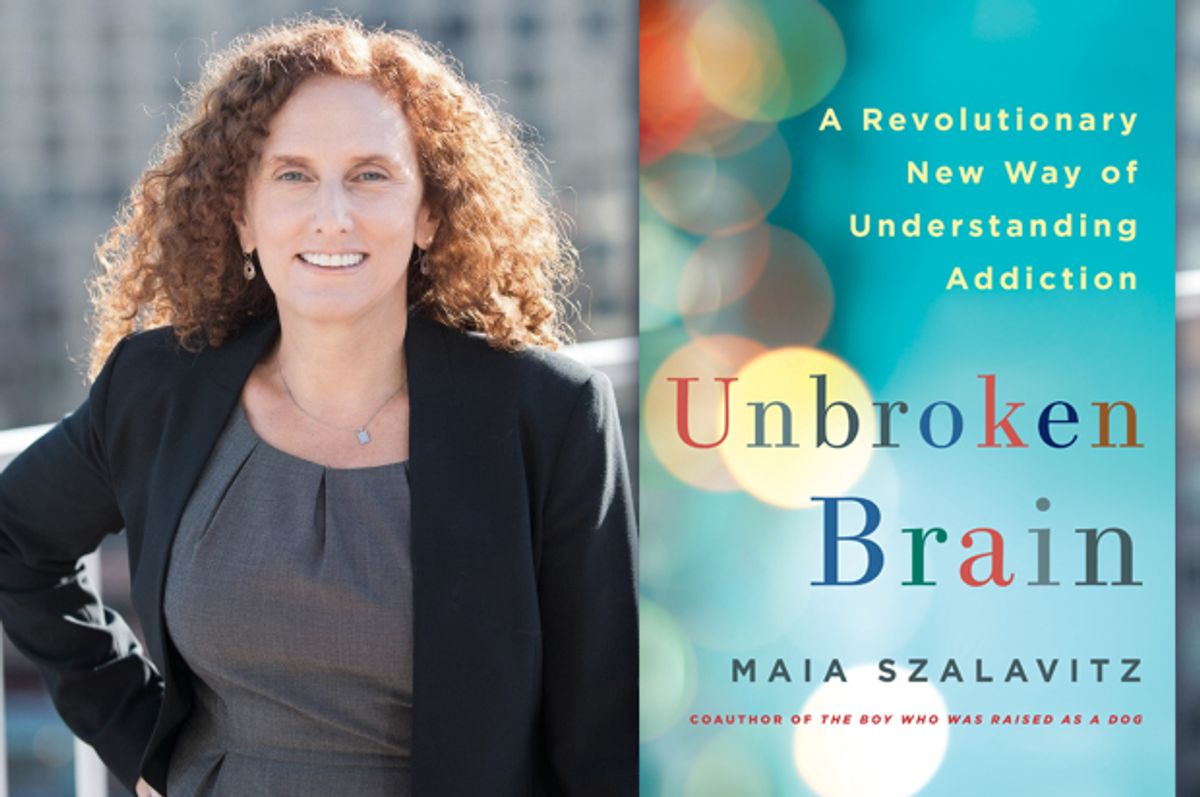

In her impressive new book, "Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction," Szalavitz dives into the science of her development, to re-think a condition shrouded in myth and misconception. Her writing is quick and sharp, and takes immediate aim at “a system that calls you ‘dirty’ if you relapse; one that assumes you are a liar, a thief, or worse.” With science, logic, and experience, Szalavitz debunks old, moralistic ideas and replaces them with elegant new ones.

Salon spoke to Szalavitz about how re-thinking addiction can lead to more compassionate treatments and policies that aim to help rather than criminalize people with different wiring. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Addiction, in your view, is a neuro-developmental learning disorder. What does that mean?

It means that for one, addiction can’t occur without learning. When I say that, what I mean is literally if you don’t learn that the drug comforts you, makes you feel euphoric or allows you to cope in some way, you cannot be addicted to it—because you cannot crave it, because you don’t know what to pursue despite negative consequences. And that’s important, because people have often thought addiction is just this physiological process that hijacks your brain. That’s really not quite accurate. It involves learning, it involves interacting with the environment, interpreting the environment, and it involves making choices.

The other reason that I think it’s important to see addiction as a developmental disorder is that 90 percent of all addiction occurs between the teens and 20s. That is similar to other developmental conditions such as schizophrenia and depression, which tend to start at that age. That suggests there is a particular period of vulnerability that the brain has and also probably has to do with your life history, as well. When you hit your teens or 20s you’re learning the coping skills you need to handle the adult relationships that are necessary for survival and reproduction. If you are using drugs to escape during this time not only is your brain developmentally vulnerable to not being able to control the use of the drug, but you’re also missing out on developmental experiences that allow you to create other methods of coping.

Your book is scientific and steeped in research, but it is also extremely personal. What was it like researching yourself? Your development?

It was funny because I have done a lot of books that I’ve co-authored with people where I have a similar structure, using their experience to explain certain types of science. I thought, oh, this will be really easy because I don’t have to nag anybody to schedule interviews; I just have to nag myself. It was a lot harder than I thought and I felt a lot more vulnerable than I expected.

Looking back on that stuff was really intense. It sometimes makes me feel old because I look back and think, how the hell could I have done that? And you know at the time it didn’t seem as absurd and messed up as it does to me now. Once you are able to have your cortex exert proper control over your behavior it comes to seem completely alien behaving as an adolescent.

You kicked for good at 23. What’s the significance of that age? What’s going on in the brain developmentally around that time?

That is very interesting, because at that age between, say 23 and 25, is when the final sculpting of the prefrontal cortex is happening. I wondered if I stopped at that age because I had an insight that I needed to stop or because I had the neural ability to carry it out. That’s really not answerable. But at that age it is definitely the case that you are finally developing self-control and greater leverage over the motivational and pleasure areas that can drive you astray.

There is the scene in which you describe having that epiphany, where afterward you voluntarily enter treatment, right around that age.

That’s the way I’ve always framed it. Especially during my 12-step days, it made a good story. I certainly wasn’t being dishonest, that is how I believed it happened. It’s really difficult to determine causality in your own behavior and that’s actually one of the points I’m trying to make in the book. People always ask, “Well, how’d you do it?” And I can only tell you how I think I did it. But I don’t have 20 identical twins that did something different so I can prove this is exactly what happened.

Unfortunately, in the addictions field, we’ve developed this idea that one size fits all, and whatever works for me is going to work for you, and we can extrapolate from my experience to be the experience of all people with addiction. That’s why I like the saying from the autism community, which is: if you met one person with autism you’ve met one person with autism. We should be saying that about addictions. I find it really annoying when people say “all addicts do X or Y.” Well, maybe you do X or Y, but don’t speak for me.

I sort of see you as this addiction myth buster.

A lot of my work has been to try and break down these myths and try to look at more of the complexity without this criminal framing.

Along those lines, the medical establishment frames addiction as a “chronic, relapsing brain disease” and yet the prescription is unscientific, like AA. You argue this bolsters the moralistic and law enforcement approaches. Can you elaborate on how these frameworks are all connected?

Imagine I’m trying to argue that the medical condition I have is a disease. But, everybody who has that medical condition can be locked up for having that medical condition, and, if they’re not locked up, they are sent to treatment that involves prayer and restitution.

So, am I going to believe that’s a disease? If I go to cancer treatment and I get told I’m going to be locked up if my tumor grows or I’m going to have to pray to a higher power and surrender in order to get better, I’m going to definitely think that I’m not in mainstream medicine. I’m definitely going to be thinking that this is not a medical condition, that it’s some kind of sin. The 12-step people don’t see any contradiction in saying addiction is a disease and the treatment is prayer, meeting, and confession. But, from the outside that sounds completely absurd. It does not bolster the disease argument at all.

When I talk about addiction being a learning disorder, I’m not saying that it isn’t a problem of the brain, obviously. I’m saying the kind of problem it is is more like ADHD than it is Alzheimer's. And I think that fits the data. If addiction is actually progressive, it should be harder to recover as you get older and that is not actually true. It also gives a much more hopeful message. Because when people hear “chronic progressive brain disease” they think dementia. When they hear hijacked brain they think: oh my god, these are zombies who are dangerous and we better lock them up for the protection of the rest of us. They think of people who have no responsibility for their actions so therefore we can treat them like children.

For all of AA’s flaws, it does seem to have stumbled upon some useful notions, such as sense of community and peer-to-peer support. For many, this is irreplaceable.

My feeling is that it doesn’t need to be replaced, because it exists! Let AA be a self-help group that provides social support. Let treatment be treatment. Don’t make people pay for stuff that you can get for free. It’s not exactly rocket science. If you use the cancer analogy, it’s like your oncologist is not your cancer support group. And you don’t take treatment advice from somebody whose only experience of cancer is having had it. You may swap information, but you’re probably better off looking to the medical literature and speaking to the medical experts.

It was your experience in AA that people were not encouraging the use of medicine, even antidepressants.

There was this idea that if you have any psychoactive substance in your bloodstream, you are therefore not in recovery anymore. And I mean people went to extreme lengths, like if you took a single sip of alcohol by mistake, then you’re back to day one. Recovery means not having that evil substance within you. It’s like, no, that is not the case.

Meanwhile, it’s okay to smoke a pack of cigarettes and drink 5 cups of coffee a day.

Well, there is that, too. What’s really important in recovery is: how are you functioning socially? Are you being there for your family? Are you being there for your partner? How are you doing in your career? That stuff is way more important than what chemicals are in your body. That is why some people can recover by moderation.

You also take aim at our drug policies. You wrote, “If addiction is a learning disorder, fighting a ‘war on drugs’ is useless.” Given this definition, why is prohibition such a futile undertaking?

The fundamental summary definition in the DSM is: compulsive behavior or drug use despite negative consequences. “Negative consequences” is basically a phrase that is synonymous with punishment. If punishment really worked to stop addiction, then by definition addiction wouldn’t exist. This seems like a really obvious point to me. But it is not obvious because we’ve continued to try and use punishment.

Think how punishing the experience of being addicted is? You lose everything important to you, pretty much (or are at risk of losing everything), yet you continue. Why would adding additional punishment like prison be any different than losing your children? It makes no sense. Since addiction is a learning disorder, the learning that is going awry is the learning that involves punishment, and you are failing to respond to punishment the way somebody would if they were behaving rationally.

It is obviously the case that sometimes people get better when faced with the criminal justice system. Sometimes they clearly don’t.

What kind of policy prescriptions do you advocate?

I advocate complete decriminalization of possession and user-dealing. Locking people up in a cage does nothing to fight addiction—it often makes it worse. In terms of marijuana: it should be legalized. It is the least harmful, not completely unharmful, but the least harmful psychoactive substance that is regularly used. It makes absolutely no sense to give that profit to the mafia.

What about other drugs?

The other drugs are more complicated and I think we need to think through very clearly the ways of regulating, like heroin maintenance and safe injecting facilities. But I personally can’t see how you deal with some of the horrific violence that goes on in Mexico without getting this money and power outside the hands of the mob.

An ideal drug control system recognizes that human beings are going to always want to get high, and tries to channel that desire towards the least harmful substances. It should also try to help the people who are prone to addiction—10 to 20 percent of the population, often heavily weighted towards people who were traumatized as children and people who have predispositions for mental illness or developmental disorders. Help those people to avoid the predisposition actually becoming the illness, i.e. reduce child trauma. Try to do things like teaching people cognitive-behavioral skills before they become depressed and before they spend 10 years attacking themselves mentally. There are all kinds of innovative prevention stuff you can do once you recognize it’s learned. Try not to get them to learn it in the first place.

That doesn’t mean that the answer is to get rid of the supply. I use the analogy of OCD (and handwashing) in the book. You are not going to stop OCD by banning X or Y hand soaps. The problem is not in the soap. While certain drugs are more harmful than others, the reason that people are desperately seeking escape is not because they’ve been exposed to a substance, it’s because the substance filled a need that helped them do something they couldn’t do without it. Unless we see that as the problem rather than the substance, we’re never going to fix this.

Where you end is a comment on neurodiversity, the idea that people with different wiring do not only have impediments, but also assets that ought to be celebrated and respected. Can you explain how this relates more to your work?

It’s quite obvious for some people on the autism spectrum that they’re quite good at things like programming but quite horrible at socializing. I think the neurodiveristy movement is really cool in valuing everybody and letting people see that what may look scary or different or totally weird on the outside may, from the inside, make total sense. It expands the world for everybody.

It’s not just that people who have disabling conditions benefit from the world being friendlier towards us, but we also benefit from being able to function and offer things that we are uniquely equipped to do. I think with addictions in particular, you can’t succeed as a writer if you can’t persist despite negative consequences.

Absolutely not.

You are going to get rejected, a lot! If you can’t deal with that then you just can’t do it. Being addicted sort of gives you a very vivid experience of the fact that you can persist. People are resourceful. If you put that resourcefulness and that drive in light of a goal that is not addiction, it can be remarkable and you can really have a lot to give.

Shares