America believes itself to be the land of opportunity. Yet both historically and presently, America has systematically denied opportunity to women, people of color and those of low-income. Indeed, the reforms that spark the most visceral reactions among many white Americans are those that simply offer Black children the same opportunities as white children, for example. (More on that later.) My analysis of American National Election Studies (ANES) data suggests that even seemingly universally accepted values are actually fraught, and divide strongly along racial lines. Rather than advance narratives that rest on individual initiative and legitimate privilege, progressives should focus on structures that perpetuate inequality and demand justice.

Whither mobility?

The idealized vision of America as a “land of opportunity” doesn’t mesh well with reality. A recent study by sociologists Lisa Keister and Hang Young Lee finds that the size of an individual’s inheritance strongly predicts their membership in the top 1 percent of net worth. Although not shown in the chart, the authors find that “above the 99th percentile by inheritance, membership in the top one percent by net worth is virtually assured.” The chart they show, below, doesn’t even include the chances of those above the top 1 percentile, because it would dramatically skew the y-axis (see chart). Other studies have also corroborated the power of inheritance: A literature review suggests that between 35 and 45 of aggregate wealth are attributable to inheritance. Opportunity is inextricably tied to race, with Black Americans having less upward mobility and more downward mobility out of the middle class.

It’s actually not clear that simply having upward mobility is a good metric for a country. Imagine a society in which every person is randomly assigned at birth to a class and then every 10 years, by lottery, they would be assigned to another class. The bottom class would own none of the wealth and the top class 99 percent of it. Such a society would have upward mobility, but it would lack any semblance of justice. Proponents of the “upward mobility” framework might argue that such a society is wrong because it fails to account for individual merit. But this ends up revealing the actual problem with mobility narratives: They ultimately rest on some vision of meritocracy.

The meritocratic ideal is flawed in a society such as ours, in which the idea of “merit” is clouded by historical circumstances, racism and sexism. Further, meritocracy places the burden of poverty on the individual, rather than society.

In addition, these narratives can hamper progressive policy. By promoting the idea of meritocracy, they strengthen the rich’s claims to their skyrocketing incomes (“I worked hard for my money”) and pathologize poverty (“They just need to pull themselves by their bootstraps”). Unsurprisingly, societies that believe “hard work” determines success are more unequal than societies that think success is determined by “luck.”

As a famous Lyndon B. Johnson advertisement once noted,

“Poverty is not a trait of character. It is created anew in each generation, but not by heredity, by circumstances. Today, millions of American families are trapped in circumstances beyond their control.”

By emphasizing upward mobility, progressives play into conservative narratives about poverty.

Opportunity for some

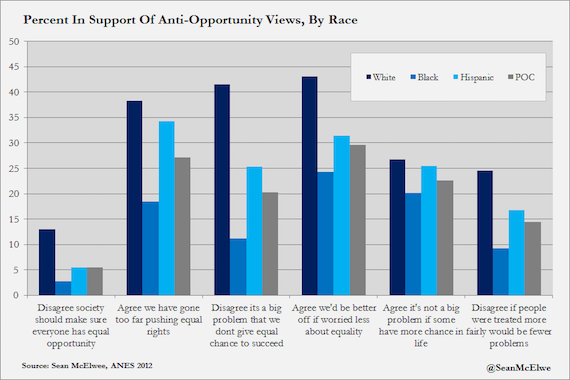

Although equality of opportunity seems like it would be a universally shared value, views as to how much the country has left to do to foster equal opportunity vary quite dramatically. In addition, there a small share of Americans who reject the idea of equal opportunity entirely. To explore the dynamics of public opinion, I turned to the 2012 American National Election Studies survey, which includes a battery of questions about egalitarianism.

Most Americans support opportunity in theory. When asked how they felt about the statement, “Our society should do whatever is necessary to make sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed,” 3.8 percent of the sample disagreed “strongly,” 7 percent disagreed “somewhat,” while 15 percent declined to agree or disagree. However, 35 percent of Americans also agree that, “We have gone too far in pushing equal rights in this country.”

To explore the demographics of opinion on upward mobility, I examined the share of people who took the “anti-opportunity” stance on each question in the egalitarian battery. So, for instance, the 26 percent of Americans who agree with “It is not really that big a problem if some people have more of a chance in life than others” would be considered taking the “anti-opportunity” position. I find that the class divides (with the exception of two questions) aren’t particularly strong. The key gaps are, first, whether it’s a big problem that we don’t give everyone a chance to succeed, and, second, whether equal opportunity would reduce problems. These data suggest that wealthier individuals are far more likely to believe that the status quo largely ensures equal opportunity. Both rich and poor accept that equality is good, but the rich are more likely to think we’re already there.

This isn’t surprising: sociologist Christina Fong finds that income effects are smaller on issues of redistribution (closely related to egalitarianism) than the effect of beliefs about how luck and hard work affect life outcomes. However, there is evidence that the context of inequality can affect perceptions of mobility. In a fascinating study, scholars Benjamin Newman, Christopher Johnston and Patrick Lown find, “residing in more unequal countries heightens rejection of meritocracy among low-income residents and bolsters adherence among high-income residents.” Thus, class position doesn’t strongly affect ideals, but does shift perceptions.

When I examine the questions along racial lines, I find larger gaps, particularly between Blacks and whites. For instance, 42 percent of whites disagree with the premise, “it’s a big problem we don’t give everyone a chance to succeed,” compared with 11 percent of Blacks and 20 percent of all people of color (all non-white respondents). Similarly, 43 percent of whites say we’d be better off if we worried less about equality, compared with a quarter of Blacks and 30 percent of people of color.

Examining net support (subtracting those who disagree from those who agree) produces even starker gaps. On net, whites agree with the statement “we have gone too far pushing equal rights,” with 38 percent in support and 35 percent opposed (the rest said they neither agreed nor disagreed). In contrast, only 19 percent of Blacks agree and a stunning 62 percent disagree. Similarly, whites on net disagree that it’s a big problem we don’t give everyone enough chance to succeed: 39 percent agree, and 42 percent disagree. In contrast, 73 percent of Blacks agree with the statement and 11 percent agree.

Idealism and reality

While Americans express support for the idea of equal opportunity in the abstract, they often oppose policies that would create opportunity for others, particularly people of color. The most fervent racial debates in our country’s history centered around the desegregation of schools. Yet far from believing that Black students should have “equal opportunity,” white parents fought fervently to ensure schools remained (and continue to remain) segregated. In reaction to Brown v. Board of Education, whites used various methods to ensure their children’s schools were not integrated. The result was that it took more than a decade for most Black children to see even modest impacts from Brown.

To this day, the funding of schools creates dramatic inequalities in education, and yet attempts to remedy the situation lead to dramatic backlashes from white parents. This can occur even in otherwise liberal enclaves. A recent episode of “This American Life” examined what happened when the Normandy School District (overwhelmingly Black) had its accreditation removed by the Missouri State Board of Education. As Nikole Hannah-Jones reports, this triggered an obscure “transfer law,” which allowed Normandy children to leave the district. However, when the Normandy prepared a plan to bus the children to a white school (Francis Howell), white parents reacted feverishly. They warned of violence, lower test scores, and an exodus of white parents. Hannah-Jones notes that “race barely comes up […] except when white parents insist it is not the issue.” She cites a mother who says,

My husband and I both have worked and lived in underprivileged areas in our jobs. This is not a race issue. And I just want to say to– if she’s even still here, the first woman who came up here and cried that it was a race issue, I’m sorry. That’s her prejudice, calling me a racist because my skin is white, and I’m concerned about my children’s education and safety.

[CROWD APPLAUDS]

This is not a race issue. This is a commitment to education issue.

Many students did end up being transferred to Francis Howell, but the problems white parents predicted didn’t come true. The episode demonstrates how white commitment to equal opportunity tends to vanish when they suspect their children might be at risk.

Similarly, scholars Allison Roda and Amy Stuart Wells report that,

“Our interviews with advantaged New York City parents suggest that many are bothered by the segregation but they are concerned that their children gain access to the ‘best’ (mostly white) schools.”

Activist Nikhil Goyal, author of the book “Schools on Trial,” notes that elites who decide public education policy frequently send their own children to exclusive private schools — suggesting their commitment to “equal opportunity,” applies to other people’s children.

In a pioneering study, “Divided By Color,” Lynn M. Sanders and Donald R. Kinder examined what predicted white opposition to various policies to reduce racial inequality. They find,

“only one result stands out consistently: whites who believe their family at risk from school admissions practices that favor blacks are generally more opposed to the various racial policies we examine.”

Americans claim to love opportunity, but American history is defined by denying opportunity to people of color.

Justice, not opportunity

There is an extent to which upward mobility acts as a convenient mythology. Research shows that the belief in upward mobility makes people more likely to accept inequality. Further, the typical narrative of upward mobility hinges heavily on meritocracy. Beliefs about how much success is determined by luck is strongly linked to the robustness of the social safety net.

If you believe the world is fundamentally just, then the poor deserve their poverty, and the rich deserve their riches. By emphasizing the individual, purveyors of “upward mobility” ignore structural barriers to human flourishing. Furthermore, they ignore that even a perfectly mobile society will still leave many people in misery, through no fault of their own.

Too sharp a focus on concepts of equal opportunity can downplay claims of justice. It’s unlikely that any society can ever have perfect equality of opportunity, and many proposals to increase opportunity ignore structural barriers to success, like neighborhood crime, segregation and entrenched racism. As Richard Reeves, Edward Rodrigue, and Elizabeth Kneebone note, poverty is multidimensional and poor people of color are less likely to have good education, live in a good neighborhood and have health insurance than poor whites. It’s difficult to wrestle with these issues in a framework focused solely on mobility. Further, as the data I’ve examined show, narratives of opportunity will end up being filtered through race and class lenses. The solution is to focus not on mushy discussions of upward mobility, which place the burden of action on the individual, but rather on the question of justice, which forces society to reckon with privilege and power.