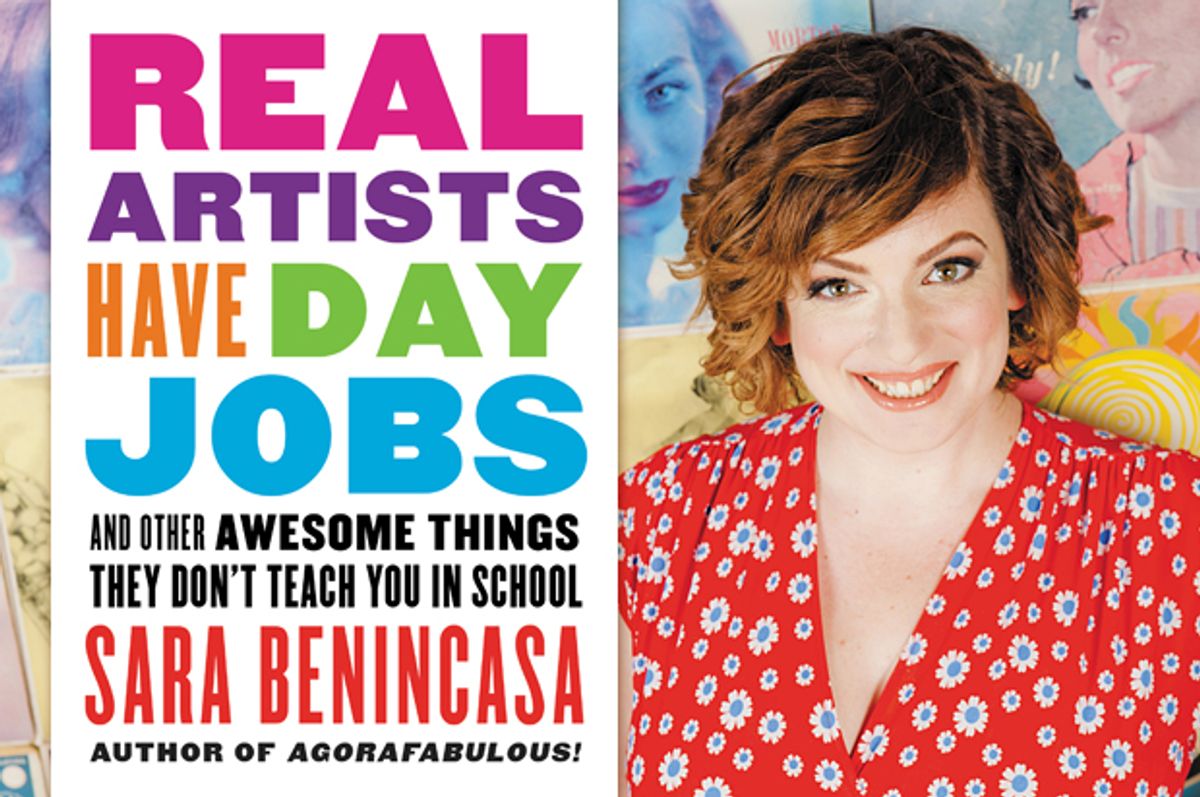

Comedian and writer Sara Benincasa has been sharing her most personal dilemmas since her one-woman show turned memoir "Agorafabulous!," about her struggle with agoraphobia. In her new essay collection, “Real Artists Have Day Jobs (And Other Awesome Things They Don’t Teach You in School),” a mix of revealing memoir and advice, she similarly delves deep into some of her biggest challenges, from mental health to abuse to having an ex badmouth her in public. From the other side of those episodes, her tone is that of a wise older sister who’s been there, done that and learned more than a few helpful life lessons (some she’s still learning) ranging from sex (“A Vagina Is Not a Time Machine”) to body image (“Realize Your Size Doesn’t Matter”).

Apropos of the title, there’s plenty of advice within these 52 dispatches for creative types about valuing your work and standing up for yourself, but even more about dealing with friends, family, lovers, pets, and, most—and hardest—of all, ourselves. Salon spoke with Benincasa about being a “real” artist, subverting the self-help genre, overcoming her own prejudices and learning to stop apologizing.

“Real Artists Have Day Jobs” stems from your Medium essay of the same name. Was there any specific incident that inspired the essay or were these things you were thinking about?

I’ve been thinking about the concept I express in the essay and expand on in the book. I think it’s really stupid and messed up that some people think that if you don’t make money as an artist because you’re busy covering other needs that you’re somehow not worthy. That’s ridiculous. The point of the essay is not that everyone is great at art or that all art is equal. Art is subjective.

The point of the essay is that whether you have a day job or a night job or a side hustle or you’re completely unemployed, you’re wealthy or you’re living in poverty or you’re somewhere in between, if you love something—a hobby or a passion, it can even be a sport—and you do that thing, then you are a doer of that thing. If you love to play basketball, you’re a basketball player. I’m not saying you’re in the NBA. But if you do it regularly, you’re an athlete, you’re a basketball player.

The same is true for artists. If you love painting and you spend most of your time as an HR rep, whether you hate or love your day job doesn't matter. If you do the painting on the side, it’s not on the side. You are a painter, that is what you are, and you can feel free to describe yourself as an HR rep on the side, or you can be both.

Do you think the idea that it’s so all or nothing discourages people from trying artistic pursuits?

I do. We put people in boxes because it makes us more comfortable. It’s easier to look at someone and say, this is a person who is a doctor and that encompasses their entire personality and mission in life. It’s more complex to say this person is a doctor, this person is a concert pianist, this person is a soccer player, this person is politically moderate, this person speaks Spanish.

We’re a culture of checking off boxes. People aren’t created on an assembly line and not everyone fits into a category, so the book talks about individuality and finding your own recipe for happiness. A huge thing for me in writing the book was to not come off as pretending to have all the answers, because I don’t; I don’t even have most of them. But I have some, and the book is based on all the times I’ve fucked up, and the very few times I’ve gotten something right the first time.

That was something very interesting to me, as someone who reads self-help books, which often have a tone of I’ve figured out everything and here I’m going to impart my knowledge. I feel like you deliberately did not come across with that attitude.

I wanted to subvert the self-help genre. I love reading self-help books; they have helped me in my life. I love when people share their knowledge. But the ones that have helped me are not books that purport to make the author sound perfect; they are books about reality and dealing with the real muck of life.

How do you walk that line of giving advice while also acknowledging that you don’t necessarily have it all figured out?

Because my background is in comedy, I’m by nature a self-deprecating person. To me self-deprecation is about disarming someone else, and showing them that if I can have a sense of humor about myself and I can poke fun at myself, then clearly I’m not going to be too judgmental of anybody else. If I regard myself as a work in progress, then I’m going to regard other people that way too, whereas if I regard myself as perfect and enlightened, then I’m going to expect other people to be at that standard, and that’s not who I am.

When I was really depressed, I would sometimes sleep with a book in my bed that I really loved, just to have it near me. I would hug it; it was almost like a teddy bear, a comfort object. I hope that this book will be that for some people as well.

From the title I was expecting the book to focus on work and career issues. You have that in there but there’s also a lot of stories and advice about our personal lives. How do you see the two as being connected?

You’re an artist full time, 24/7. That’s your job all the time and so part of being an artist is not just producing the work, it’s looking at and experiencing the world differently. For an artist, the personal and the professional are inextricably linked. If you make art, you put something of yourself into it. That sounds high minded, but it’s realistic. You don’t get to make art without some metaphorical and often literal blood, sweat and tears.

You talk in the book about radical self-confidence and you also have a chapter about why we should elect our own executive board of smart, knowledgeable friends we can consult for advice. I thought those were an interesting counterbalance. How can people navigate both having that radical self-confidence and knowing when is an appropriate time to ask for advice?

I’ll give you an example. Last night I was really sad about something. I was crying and I was talking to a friend, and the friend said, “Sara, all the answers are inside you.” And I said, “Yeah, that’s true, but I know when I need somebody to get those answers out.”

So to me, asking for help is a sign of self-confidence. It’s not a sign of weakness; it’s a sign of strength, because when you ask for help you indicate that you are worthy of assistance, that you want to get better, that you deserve to stick around. That's true for everyone, but not everyone knows that.

Having the radical self confidence to say, no, I don’t want to keep feeling terrible and I don’t want to keep living with less than I deserve, may come in the form of a 911 call, literally. There was a point in my life where that came in asking a friend to take me to the emergency room. That can be at your lowest point. It can also be as simple as asking a neighbor for assistance in the yard.

I find that it’s often the people who don’t ask for help who are in the most trouble. They sometimes get to a place where they’re so far gone, and they’ve never indicated the need for assistance. That’s heartbreaking because sometimes they don’t make it, and I want people to make it.

I’ve also noticed over the years, that it seems when someone who’s very revered publicly admits they’re having trouble and asks for help, that makes people feel so relieved about themselves. It actually gives people more respect for that person. Someone will say, I was never a follower of her before, but once I heard her open up about that situation, then I really wanted her to succeed and I was so impressed by her.

Last night when I was really sad and I was crying, I got a lot of stress out. It was sad but it wasn’t scary. When I was younger it would have been scary. I would have been afraid and panicked about it, but because I’ve asked for help in the past, I knew I could do that now. I knew it was going to be okay.

What’s the most challenging piece of your own advice in the book for you to take?

“Walk your way to a solution” is tough. I’ve always been pretty sedentary. I wasn’t naturally good at sports so I grew up being scared of being physical. I just scheduled a personal training session. Brain stuff comes relatively easy to me; body stuff does not.

The chapter [on] “Abuse is fucking complicated.” That sometimes is difficult for me, because if you’ve been abused in some fashion, it’s really hard to accept that that’s that that was, because nobody wants to feel like a victim; nobody wants to feel powerless.

Also, to “feel all the feelings.” That’s the toughest of all. Not to honor each and every one as precious and beautiful, but to deal with your shit. I didn’t emotionally deal with a breakup and I distracted myself in different ways and that grief comes out.

The challenge is to deal the feelings as they come up, and that’s hard. I was upset about something yesterday and I was buying pepper spray and I was wearing sunglasses because I thought I was going to cry. I wanted to get it out, but I had to buy this pepper spray You don't always have time to set your shit aside and just feel the feelings. It’s about experimenting with feeling a little bit of them when you can.

One of the most moving chapters was on dealing with personal prejudices. You talk about having grown up going to Catholic church and getting rid of some of the prejudices you were taught but that transphobia was one that stayed with you into your twenties. Can you talk about how your thinking changed?

I think that everyone, even the most open-minded person, has certain prejudices. We decide what is normal in our world, and when someone challenges it with their normal, that can blow our minds. My thinking changed because I was challenged on it. I was challenged on [my] casual transphobia; it wasn’t let’s-go-beat-up-trans-people transphobia. It’s usually not as dramatic as that. It’s the casual sexism, the casual racism, the casual homophobia, the stuff that’s built into the system of society, of your workplace, of your family, and you don’t realize it’s a bad thing sometimes until somebody calls you out.

What I have noticed is that people respond much better to being called out face to face. Not because the person is trying to win points by being the coolest liberal in the room or something ridiculous like that, but because somebody cared enough about you to say, here’s why what you said isn’t cool. It hurt my feelings, here’s why, but coming from a place of respect.

In this case, somebody called me out in person and it was so smart. I’m really glad that that happened. It was embarrassing at the time. When you realize the joke you made isn’t funny, especially when you’re a comedian, that goes to the ego.

The most important thing beyond that was having people in my life who were trans. We talk about these lofty terms, visibility and representation, but it’s actually pretty simple: if you see people of all different types out in the world, then it becomes your normal. I began to have not only friends who had transitioned but friends who were in the process of transitioning. It’s hard to make fun of somebody when you’ve looked into their eyes and you know their pain and you know their joy. You can make fun of them for stuff like watching stupid TV shows, but to mock someone’s identity becomes very difficult when you see how hard they’ve fought to claim that identity.

I shared stories in the book of my own fears and prejudices because I want people to see somebody talk about flaws and show that you can change. I felt out of place and dorky at school, but at church I found solace in a belief system they were spoon feeding me I could just sign on to. A religion is just a cult that’s been successful for a few thousands years. So my particular McDonalds was anti-gay and anti-abortion and when I was in eighth grade a lady came and showed us pictures of dead fetuses, so I believed all that. It gave me an identity; it gave me something to cling to, and certainly transphobia was part of that.

They didn’t sit us down and say “be transphobic,” but they taught us that queer people had been given a burden by God, and this burden was the desire for same-sex people or the desire to be a different sex or gender; it was like Christ’s cross. So if they bore that without giving in to it then they would find happiness in heaven. That made sense [to me]. I was also taught that if a woman or girl was raped, she should carry the baby to term because the baby was the blessing that came out a terrible crime and that God would reward her for that. I believed all that.

Religion definitely fucked me up, but I am glad for it because it helps me have genuine empathy with people who still believe that. If they’re going to keep using that as a weapon against others, fuck them, I think they suck, and I will fight against them. But when I see a mother who’s struggling with having a gay son, my default isn’t to say she’s garbage; my default is to say, with some time and some education, she could come around. But I’m here for the kid first and foremost.

Especially online, people can get very polarized and see people, whether it’s that mother who’s struggling, and see someone who has different political ideals, as the enemy. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I’ve definitely been angry online. Right now I’m pretty chill cause I’m sitting in the sunshine and my hair looks good today and I’m sipping on iced green tea. But catch me at a moment where I’m feeling low or I’ve just talked to a kid who’s in a lot of pain, I will fulminate and rage against what I perceive as the machine. The internet is the enemy of nuance in many cases. There’s beautiful writing online; that’s where I read 90 percent of what I read, that’s where I write a lot of what I write, but the temptation is always there to press a button and broadcast a gut reaction to the world.

I did that recently and had a friend say to me on Facebook, you sound like an asshole right now. I realized they were correct. I was mad about somebody who was rude to a friend of mine and I didn’t think about the context of the situation. It’s easy to regard people as cartoon villains on the web because they’re not in front of you. If you can look into somebody’s eyes, it becomes very hard to vilify them. Unless it’s Donald Trump; that guy’s a fucking asshole.

The hardest thing for me to follow from your book is not apologizing. I did it when I was rescheduling our interview. Even when I was trying not to, I couldn’t stop myself.

I also understand there’s a place for it. It’s perfectly fine to say, I’m sorry I had to reschedule an appointment and then give a reason, without beating yourself up. [You can say] “I’m sorry I had to do this potentially inconvenient thing; here’s why.” There’s a difference between that, which is out of understanding you may have inconvenienced someone, and saying to your gym buddy, I’m so sorry I spend too much time on the treadmill or apologizing to your husband or boyfriend for being too fat or for not moisturizing. Women will apologize to inanimate objects for bumping into them; I have done it myself. We apologize for taking up space in the world. It’s not just women, but it’s an epidemic among women. Anyone who’s been made to feel that they don’t deserve to take up space in the world will often deal with it by either being abusive to others or by constant apologies.

How have you worked on that for yourself?

Somebody pointed it out to me and questioned it. I learned to pause. Take a second, take a breath, and ask yourself, am I really sorry? Sometimes it’s yes, of course. Other times I was just saying I was sorry because I wanted them to be kindly disposed to me. If your sorry can’t be authentic, it should at least be strategic; it shouldn’t be something you throw out there willy-nilly because you were taught to apologize. It certainly shouldn’t be “I’m sorry but __” fill in the blank insult.

Shares