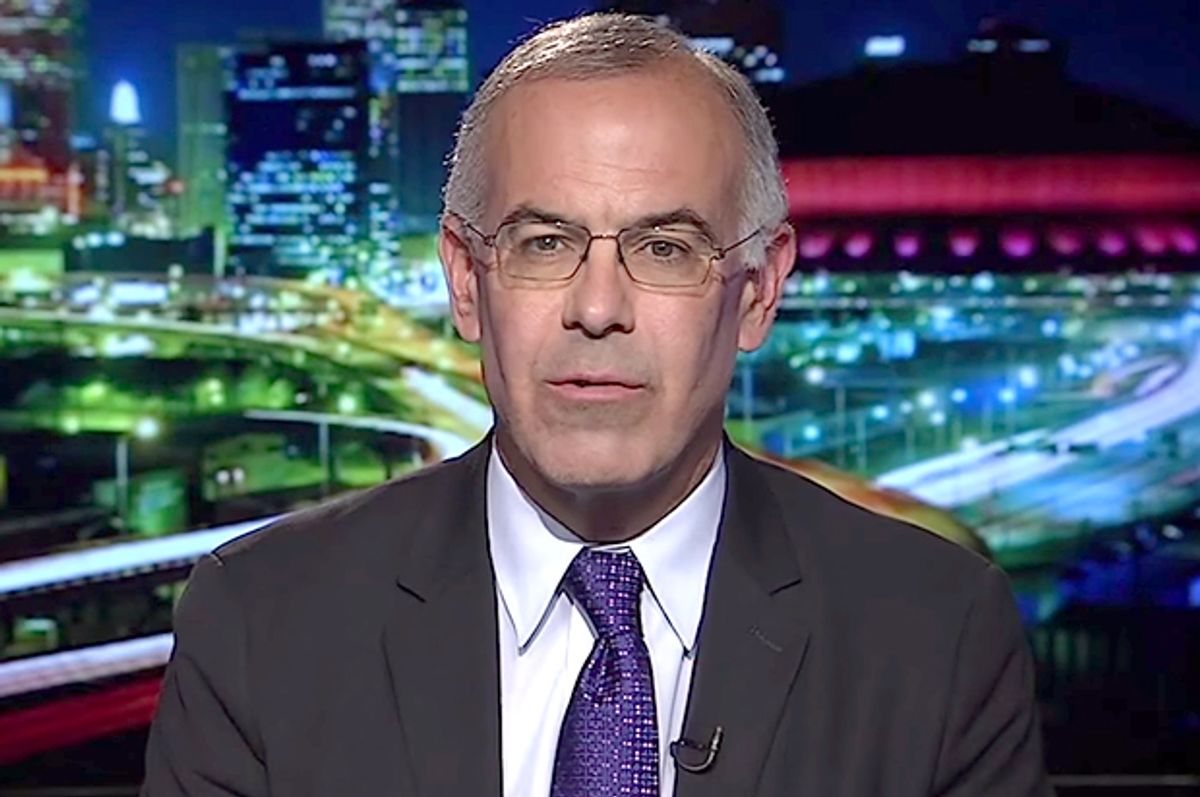

Sometimes, I’ve been close to deciding that New York Times columnist and all-around pundit-for-hire David Brooks writes solely to make those of us who read him crazy. Now I’m convinced of it.

One of the things that has bugged me most in his columns has been his over-the-top smugness, the sense of entitlement Brooks exudes. Now, to make matters worse for me and the rest of his readers, he admits it:

I’ve slipped into a bad pattern, spending large chunks of my life in the bourgeois strata—in professional circles with people with similar status and demographics to my own.

To remedy this, Brooks writes that he’s going to take his column “across the chasms of segmentation that afflict this country.”

That’s rich.

He’s right, though, when he claims that the United States has reached a critical junction for conservatives, “that this is a Joe McCarthy moment.” He’s referring to the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954, when chief counsel for the Army Joseph Welch exploded at the sodden senator, “You've done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” Brooks seems to be reading the question today as addressed to himself and the other leaders of the Republican Party and the conservative movement—especially those toying with the idea of going with the flow and supporting Donald Trump. Give Brooks credit: He recognizes that the easy way out is to turn to Trump and hope for the best, throwing away belief in order to grab the coattails of victory.

Or imagined victory. I have a friend, a Trump supporter, who argues that even Latinos will come around to supporting Trump by November. To me, this is simply an extension of Trump’s "everybody loves me" magical thinking. Brooks, quite clearly, thinks so too. Having seen conservatives compromise themselves for victory for a generation now, Brooks has had enough—which is what makes this a McCarthy moment for him.

His atonement, his alternative, though, is fraught with danger for someone who has hitched his wagon to the star of American elitism.

The fantasy that the wealthy can learn to understand how the lower classes live goes back a long time. Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper, published in the 1880s, lampoons the idea, though gently, as does the 1936 movie My Man Godfrey. The main characters do learn, but these are clearly fairy tales—no one is expected to believe this can really happen. Sullivan’s Travels (1942), though a wonderful satire, also ends in fairy-tale land—as do most others that tackle the same topic.

As will Brooks, if he’s not careful. Remember John Howard Griffin and Black Like Me, his account of darkening his skin and passing as an African-American? The experience may have given him a bit of an idea of what it was like to be black in the American South in the 1950s, but there was a great deal more to the real experience than color. The cultural baggage of slavery, Reconstruction, decades of Jim Crow cannot be experienced by someone who did not grow up carrying it.

No matter what he does or who he talks to, Brooks is now so far removed from the experiences of the rest of us in America that he will never understand. Not likely, at least. His own column makes that clear. Though he says he wants to listen and learn, he’s already envisioning his journey in terms of narrative, not reality: “We’ll probably need a new national story.” From the looks of things, he may believe that he’s the one to provide it. That won’t work: he should be looking for what’s already there—though he’s not likely to find it.

One of the dangers of whites writing about the black experience in America (or vice versa, quite frankly) is that, as Griffin’s book shows us, an outsider can never get to the heart of the experience. Even Neal Gabler, whose “The Secret Shame of the Middle Class” in The Atlantic has been stirring up discussion, is learning that his experience of financial woes is different from those who have never sold a book to the movies. His good fortune has moved him far from the increasingly hardscrabble life of most Americans for whom paycheck-to-paycheck is no longer enough for what had once been seen as the basics of middle-class life.

Brooks ends his op-ed with advice to himself: “time is best spent elsewhere, meeting the neighbors who have become strangers, and listening to what they have to say.” Thing is, I don’t think Brooks has neighbors anymore, not in the sense of the old American middle class.

If he wants to learn about America, he’s going to have to live it, not simply visit it on a planned tour like his recent one of Cuba.

Shares