Medora is a small, seasonal tourist town in the Badlands of western North Dakota, about 25 miles from the Montana border. It has a population of less than one hundred. It went for John McCain for president by a three-to-one margin in 2008. A handful of small stores are in the center of the town—some gift shops, a bookstore, an ice cream shop, two restaurants, a museum, and a hotel that’s full during tourist season.

Around the corner from downtown is the Rushmore Mountain Taffy and Gift Shop (not to be confused with the Rushmore Mountain Taffy Shop at the base of Mount Rushmore in South Dakota). You wouldn’t know it by looking at it, but the Medora taffy shop was the first legal home of a media organization that now provides a significant amount of political news coverage in 39 state capitals through 55 interconnected news sites, according to a local reporter who was curious about the entity and asked around.

At the start of 2008, the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity had a budget of zero dollars. Its legal home was the taffy shop in Medora. By 2009 the Franklin Center’s budget had jumped to $2.4 million, according to IRS tax records. That’s a spectacular leap for a nonprofit, especially in Medora.

It was almost as if someone wished to utilize the charter concept of the Franklin Center—developing individual but interlinked news centers across the United States that would all promote the same messages—for other purposes and therefore infused it with a mountain of funding and network support. Intriguingly, this was a year before the Tea Party movement seemingly sprang from nowhere and spread like a prairie fire to the thirty-nine state capitals where the Franklin Center now operates its news sites.

The Franklin Center has a second address—a post office box in Bismarck, North Dakota, where mail is forwarded east to Old Town Alexandria, near Washington, DC. North Dakota law requires that nonprofits have a “physical address,” not just a forwarding address or a post office box. So, for years, the Franklin Center’s registered agent was at the taffy shop, while the mail was forwarded from the UPS store in Bismarck.

The Franklin Center’s president is Jason Stverak. He used to be the executive director of the North Dakota Republican Party. He also ran Rudy Giuliani’s presidential campaign efforts in the state. But just prior to starting the Franklin Center, he was the regional field director for the Sam Adams Alliance, where, according to his Franklin Center bio, he “worked with state groups and associations committed to promoting the free-market policies” that are now embedded in every political story that the network’s reporters write about in state capitals across the country.

“An expert in non-profit journalism, Jason works to promote social welfare and civil betterment by leading initiatives that advance investigative journalism,” his Franklin Center bio reads. “His support of non-profit journalism has played a vital role in exposing corruption in our elected officials and encouraging transparency in government.”

The Franklin Center grew from nothing in 2007–08 to the largest network of local political reporting in the country almost overnight. Its 55 news sites generally cover political events or issues from an antitax, antiregulation, or antispending frame. While each of the sites has its own team of local reporters, they generally tend to share common themes across the entire network of coverage, recent studies have shown. Government is either working badly and needs to be exposed; or local initiatives are spending far too much money; or politicians are unjustly pushing for excise taxes on oil or gas or cigarettes; or the local governments are burying citizens in regulations and bureaucracy.

The Franklin Center describes most of its reporters in the state capitals as “watchdogs,” constantly looking for excise taxes that need to be rolled back or government initiatives and regulations that need to be curtailed. The organization was built to “address falling standards in the media as well as a steep falloff in reporting on state government,” its mission statement says. It “provides professional training; research, editorial, multimedia and technical support; and assistance with marketing and promoting the work of a nationwide network of non-profit reporters.” It supplements that watchdog reporting in state capitals with its “newly launched Citizen Watchdog program that trains ordinary citizens to report from local communities.”

In many of the state capitals across the United States, especially in the less populated red states, the Franklin Center news sites are a significant source of local and statewide political news. “Specializing in state and local government, [the] Franklin Center has focused its efforts on reaching maximum penetration within small and mid-sized media markets—on driving a conversation about transparency, accountability, and fiscal responsibility at the grassroots level and putting a human face on public policy,” it says. “We specialize in reaching a layman’s audience through local media, coordinating our nationwide network to ensure that we are hitting this audience in every state.

“[The] Franklin Center was founded in 2009 to help fill the void created as the nation’s newspapers cut back on their statehouse news coverage and investigative reporting in the wake of falling circulation and revenues. Our goal is to provide fresh, original, hard-hitting news content that is published on our own Web sites and in traditional media sources.”

While each of the local sites and reporters cover their own beats and stories, they all share a common goal and platform. “All publications have a mission and a voice. We are unabashed in ours: to spotlight waste, fraud and misuse of taxpayer dollars by state and local governments. We always ask these questions when reporting on events: What does this mean for taxpayers? Will it advance or restrict individual freedom? We look at the bigger picture, provide analysis that’s often missing from modern news stories, and do more than provide ‘he-said, she-said’ reports from the state Capitol. Our journalists look for the back story and offer much-needed perspective on the day’s news.”

That context—multiple news outlets with the same underlying themes— is what makes the Franklin Center unique. State legislators have come to accept a certain style of coverage from its local news sites, which have names such as KansasReporter.com, PlainsDaily.com, or CapitolBeatOK.com, and they are rarely disappointed. The state legislators and local readers also aren’t generally aware that a national center is directing traffic.

Beyond its news sites and paid reporters, the Franklin Center also trains an army of citizen journalists who will blog and comment on taxes and government in state capitals. “We’re leaders in the new wave of non-profit journalism. We have reporters, news sites, investigative journalists and affiliates across the country—and we’re growing. In addition to our nationwide team of professional journalists, we are expanding our reach into citizen journalism,” it says. “We provide training to these citizen watchdogs so that they can better employ journalistic standards as they keep their local governments accountable through their blogs and Web sites. While distinct from our journalism efforts, this new wave of information activism will help fulfill Franklin’s vision of creating a more vibrant democratic society based on accountability and open government.”

Like the Sam Adams Alliance training sessions that were conducted under the umbrella of Americans for Prosperity in the year or so prior to the Chicago Tea Party event, most of the Franklin Center’s training sessions for citizen journalists are likewise conducted in partnership with Americans for Prosperity.

A training session in Omaha, Nebraska, in the fall of 2013 is a good example of this partnership. The session was free, sponsored by the Nebraska AFP chapter. The Franklin Center ran it for two nights (and included conservative activist James O’Keefe, who filmed ACORN events under cover, creating a firestorm of controversy).

“Nebraska and our nation are in a fiscal crisis,” the AFP’s Facebook event page said, describing the training session. “You’ve heard the egregious examples of waste, fraud and abuse on a daily basis. We can no longer afford to sit by and wait for the government or mainstream media to fully inform the public about what’s going on behind closed doors. The time has come to stand up and take action. Together, we can begin the hard, but important job of taking back America.”

In an era where old media is being replaced rapidly by digital media and citizen journalism, nonprofit media organizations are paying close attention to the ways in which philanthropy is intersecting with journalism. They are amazed at the rapid growth of the Franklin Center because it has been extraordinarily successful at a time when local investigative journalism efforts—even those supported by philanthropy—have struggled to take hold. Even the largest news organizations in the world are struggling to survive.

The New York Times has gone through several rounds of buyouts and forced layoffs in the last three years, for instance. Every major newspaper in the country is struggling with the transformation to the digital age of media. An American Journalism Review in 2009 found that the number of reporters covering state capitals had fallen 30 percent since 2003.

Yet the Franklin Center flourishes. Why? Because it has deep financial pockets and no worries about its funding. National Journal reported that the Sam Adams Alliance provided the seed money to launch the Franklin Center in the months prior to the Chicago Tea Party event, taking the funding from zero to $2.4 million in 2009, then to $3.7 million the following year.

Besides operating a group of paid national reporters who focus on state capitals as well as a group of citizen journalists blogging in these state capitals, the Franklin Center also supplies grants to each of the fifty-five sites in the thirty-nine state capitals.

Its success—basically, the reason that it has no need to fight for its survival when every other local digital journalism effort does—is almost certainly due to its connection to the Koch donor network. Like other related groups with operations in the DC area, the Franklin Center benefits greatly from the Koch donor network’s Freedom Partners.

The Franklin Center’s director of donor development, Matt Hauck, worked for the Charles G. Koch Foundation. Its senior vice president in charge of strategic initiatives, Erik Telford, worked for the Kochs’ Americans for Prosperity before joining the Franklin Center. The founding board member who set it up was Rudie Martinson, who helped run Americans for Prosperity in North Dakota. Martinson is still on the Franklin Center’s board. One of the founders of the Franklin Center, John Tsarpalas, is a past president of the Sam Adams Alliance and director of the Illinois Republican Party.

The Franklin Center operation works quickly and efficiently. Here’s a good example, from a report by the Center for Media and Democracy. In 2012, the Idaho legislature took up a bill that was designed to keep minors from going to commercial tanning salons. It was uncontroversial—other states have instituted similar restrictions for minors due to concerns about the dangers of skin cancer—until the Idaho Reporter (one of the Franklin Center’s news sites) took up the issue in force. It posted six stories on the tanning-bed bill between February 16 and March 22 of that year, claiming that passing such a bill represents a “huge overreach by the state . . . an infringement upon a family’s right to make these kinds of choices.” A state Senate committee then voted the bill down.

Former Reuters chief White House correspondent Gene Gibbons conducted a review of statehouse coverage by traditional media outlets shortly after the spontaneous combustion of the Tea Party movement in 2009— and ran smack into the Franklin Center network. He was surprised at what he found, he wrote in his study for the NiemanReports publication of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard in 2010.

“For the most part, the people in charge of these would-be watchdog operations are political hacks out to subvert journalism in their quest to grab and keep power using whatever means they have to do so,” Gibbons wrote. “At the forefront of an effort to blur the distinction between statehouse reporting and political advocacy is the Franklin Center.” He added that such efforts were “political propaganda dressed up as journalism.”

Gibbons interviewed Jason Stverak in the spring of 2010 for the Nieman Foundation report. Stverak told him that the Franklin Center journalists were held to the same journalism ethics as those from traditional newspapers. They should be judged “based upon the content that they produce,” Stverak said.

But when Gibbons looked into how the Franklin Center went about its business, he indeed found “political propaganda dressed up as journalism.” Four months after he interviewed Stverak, Gibbons wrote, “The Franklin Center co-sponsored and played an active role in a two-day conference organized by Americans for Prosperity Foundation. The Right Online Agenda conference included such breakout sessions as ‘Intro to Online Activism’ and ‘Killing the Death Tax’ and featured speakers such as conservative U.S. Representative Michele Bachman of Minnesota and Tea Party activist Sharron Angle, a Republican who was then running against Harry Reid in the election for U.S. Senate in Nevada. No Democratic legislators were included in the program. The finale of the Las Vegas conference was a ‘November is Coming Rally.’ ”

But Gibbons also said that this was likely the future of some form of journalism and cited conservative columnist K. Daniel Glover in a subsequent report in June of 2010 on the trends for the Kennedy School of Government’s Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy.

“Once conservatives realize they can conduct great investigations that expose the flaws of intrusive government and the special interests that corrupt it, you will see more of them embracing that kind of journalism,” Glover told him. “Mainstream publications like the [Washington] Examiner and organizations like the Franklin Center . . . which helps support and fund budding watchdogs, are showing them the way.”

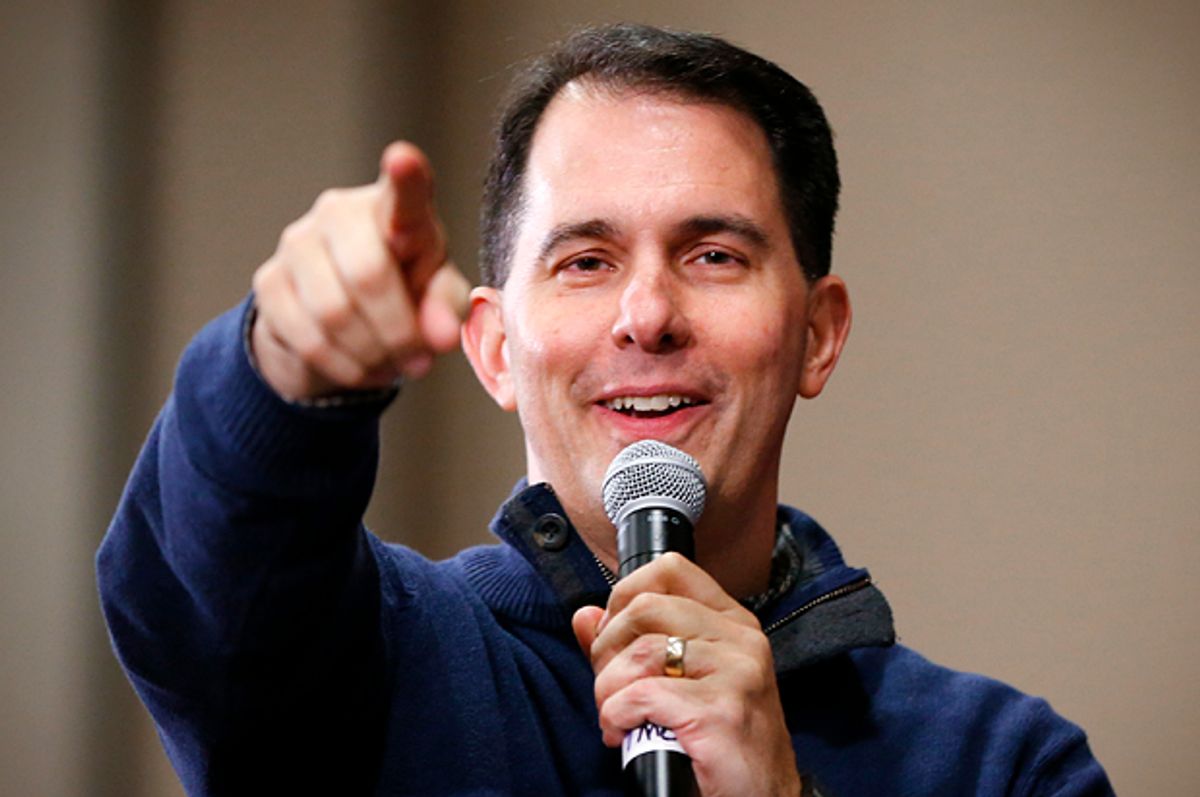

The Franklin Center sites also clearly drive follow-on news coverage, often uncritically. Its Wisconsin Reporter, for instance, once sponsored a poll that found more than 70 percent of people in the state supported an effort by Governor Scott Walker to cut the collective bargaining rights of the state’s public sector workers—a fight that angered the unions of teachers and other public sector workers. National news organizations, including MSNBC, picked up the coverage and reported on the poll.

In his study, Gibbons found a highly leveraged network of sites: “The State Policy Network–Sam Adams Alliance–Franklin Center troika is at least loosely associated with more than a dozen other conservative groups funding news sites in various states.”

By 2011, according to CMD and others, the Franklin Center had more than tripled in size from its 2009 start. Donors Trust, a 501(c)(3) charity whose Web site says they encourage giving to “fund organizations that undergird America’s founding principles,” alone provided $6.3 million to the Franklin Center in 2011, according to those reports. Mother Jones called Donors Trust “the dark-money ATM of the conservative movement” in a 2013 article. The Franklin Center was the second-largest recipient of Donors Trust funding in 2011. A central contributor to Donors Trust is the Knowledge and Progress Fund founded and run by Charles Koch.

Today, Franklin Center reports make the national news circuit through the Fox News Channel, the Washington Examiner, and The Daily Caller and hit the front page of the Drudge Report consistently. For instance, at the end of October 2014—just a few days before the midterm elections, its Wisconsin Reporter story about Governor Scott Walker’s opponent in his reelection fight (Democratic gubernatorial candidate Mary Burke) was highlighted by Rush Limbaugh.

“Now this story hit,” Limbaugh said on his popular, syndicated radio program. “It’s a story about Mary Burke, the Democrat candidate there, and how she was fired from the family business for incompetence. Whatever the family business is, she was fired from it. She’s seeking the governorship in Wisconsin, and the point is, if her own family had to discharge her from the family business because of how much she gunked it up, then what business does she have being elected governor?”

Needless to say, Burke contested the news story. But the damage was done, with little time to deal with it publicly before the election.

One thing is also obvious from this episode. What began as a novel concept—shaping media coverage from a libertarian perspective by becoming the media and presenting only one side of an issue—in the years and months prior to the spontaneous rise of the Tea Party in Chicago in 2009 may now, according to Gibbons and others studying the intersection of philanthropy and journalism, become the norm for the way in which news is conveyed in American democracy.

Excerpted from "Poison Tea: How Big Oil and Big Tobacco Invented the Tea Party and Captured the GOP" by Jeff Nesbit. Published by St. Martin's Books. Copyright © 2016 by Jeff Nesbit. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares