When did Keith Richards take his first hit of heroin?

Even he doesn’t know.

He says it was probably an accident, that he mistook a line of smack for a line of blow at a party at the rag end of the decade. It was everywhere. Cheap, nearly impossible to avoid, an unintended consequence of the Vietnam War. When we opened a channel to South- east Asia, soldiers flowed out and china white flowed in.

Heroin had been a passion of Keith’s heroes—black blues players who’d chased the high until they lost everything. If you’re of a certain temperament, you do things you know are bad for you because without the experience, you can’t emulate the art. To make music with the depth of the masters, Keith had to experience what they experienced, had to touch the seafloor, where the pearl is buried in the muck. When he speaks about his junkie years—“I know the angle,” he told Zigzag magazine in 1980, “waiting for the man, sitting in some goddamn basement waiting for some creep to come, with four other guys sniveling, puking and retching around”—it’s not without a certain pride. Fame removed Keith from the kind of suffering that stands behind the Delta blues. He’d never know cotton shacks or rent parties. He sought that crucial authenticity in debauchery instead.

Heroin was in part Keith’s response to Altamont. He reeled from riot to stupor. He loved how it made him feel—how it answered every question, removed every obligation, annihilated every stare. (“I never liked being famous,” he said.“I could face people a lot easier on the stuff.”) Like prime rib with cabernet sauvignon or creeper weed with high school, junk went perfectly with that bleak, washed-out moment. Vietnam, the streets filled with psychotic vets, LSD cut with strychnine, Richard Nixon in the White House. The shift from the sixties to the seventies was the shift from LSD to heroin. LSD was aspirational. Heroin was nihilistic. The promise of hippie epiphany was gone; only the high remained. Keith came to personify that—the oldest young man in the world; stand him up and watch him play; shoot him up and watch him die.

*

The Stones were in the same condition as the culture, having come to realize, despite all their hit records and sold-out shows, that they were essentially broke. When they asked Allen Klein for more of what they assumed was their money, he sent it grudgingly, in dribs and drabs. Jagger finally reached out to his friend Christopher Gibbs, the art dealer, who put him in touch with the private London banker Prince Rupert Loewenstein. At first glance, Loewenstein, a prematurely middle-aged aristocrat who spoke with a slight German accent, seemed an unlikely partner for the Stones. “My tastes . . . leaned towards Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms,” Loewenstein writes in his memoir.“The name of the [Stones] meant virtually nothing to me at the time, but I asked my wife to tell me about them. She gave me a briefing and my curiosity was tickled.

“Mick slipped into the room, wearing a green tweed suit,” Loewenstein goes on.“We sat and talked for an hour or so. It was a good, long chat. His manner was careful. The essence of what he told me was,‘I have no money. None of us have any money.’ Given the success of the Stones, he could not understand why none of the money they were expecting was even trickling down to the band members.”

It took Loewenstein eighteen months to untangle the contracts and deals. He explained the problem to the band in 1970: Klein advised you to incorporate in the United States for tax purposes; as this new company was given the same name as your British concern— Nanker Phelge (named after their old Edith Grove housemate)— you’ve assumed it’s the same company; it’s not. The American Nanker Phelge is owned by Allen Klein; you are his employees. Royalties, publishing fees—all of it belongs to Klein, who can pay you as he sees fit. This also gives Klein ownership of just about every one of your songs. “They were completely in the hands of a man who was like an old-fashioned Indian moneylender,” Loewenstein writes, “who takes everything and only releases to others a tiny sliver of income, before tax.”

Jagger was humiliated, ashamed. Here was the smartest rocker, the LSE student, being taken in a game of three-card monte. “There was one frightening incident in the Savoy Hotel when Mick started screaming at Klein who darted out of the room and ran down the corridor with Mick in hot pursuit,” Loewenstein writes.“I had to stop him and say,‘You cannot risk laying a hand on Klein.’”

Loewenstein proposed a two-step course of action. One: the Stones immediately sever all ties with Klein. The second step had to do with Inland Revenue, as the British equivalent of the IRS was then called. As Klein had cashed checks from Decca, he never withheld or paid the band’s taxes. The musicians had accrued a tremendous debt as a result. Not only were they broke, they were in danger of being sued. What’s more, the Stones’ earnings—on paper—put them in the top bracket, which in Britain at the time meant paying a marginal income tax rate of up to 98 percent. In other words, the government would take almost everything you made over a certain amount. This made it nearly impossible for the Stones to earn enough money to ever satisfy Inland Revenue. If they wanted to live safely in England, they’d have to move somewhere with a less punishing structure, then make enough money to square themselves. The term for this is “tax exile.”

“My advice is contained in four words,” Loewenstein told Jagger. ‘Drop Klein and out.’”

The Stones broke with Klein in December 1970, then sued for $29.2 million. A settlement for $2 million was reached in 1972, though litigation carried on for years.

As for exile, Loewenstein suggested France. The prince, who had pull with Parisian officials, was able to arrange a deal: the Stones agreed to stay in the country for at least twelve months and spend at least £150,000 per year; in return, no additional taxes would be levied by the French government. Band members began leaving England in the spring of 1971.

Keith and Anita quit heroin before they went into exile. They did it to avoid certain hassles. Being addicted means having to carry drugs, hook up with local dealers—expose yourself in a million dangerous ways. Keith kicked first. Vomited and wept; wept and prayed. He was clear-eyed when he arrived at Gatwick Airport in April 1971, twenty-seven years old, the coolest person walking the planet other than Elvis and Brando, but Elvis and Brando were past their prime, slouching toward late afternoon, whereas Keith was at his apex. In photos taken that day, he has the look of a man used to being looked at. The sharp angles and rock star lines that would later characterize his face had not yet hardened. He carried his son, Marlon. Anita was in London, in the midst of withdrawal. She would join Keith and Marlon in France as soon as she was clean.

A house had been selected for the family in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a port on the Côte d’Azur. Fleetingly small, bathed in boredom and sunlight. Nothing is happening. Nothing has happened, or will ever happen. Exactly what Keith required. I visited the town shortly before my mother died—checked in to a hotel on the harbor, talked to strangers, walked. The ancient streets are steep and shaded by plane trees. There are alleys and storefronts and wine shops that reek of time. In the summer, the squares are picked clean by le sirocco, a wind that originates in the Sahara and covers the rooftops in fine red sand. What you feel in Villefranche is not the Stones but their absence. The world’s most powerful rock ’n’ roll energy had once concentrated here, but that was decades ago. The bars where the boys once drank as the sun went down are long gone. What remains is the silence that you hear as you sit alone in a hotel room after the last song has played.

I hailed a taxi in front of my hotel and asked the driver to take me to the house where Keith and Anita once lived. He had no idea what I was talking about, so I asked him to take me to the house where the Stones recorded Exile on Main Street. Still no idea. So I told him about the summer of ’71, the mansion in the hills, the drugs and the songs. He said “Oui, oui” but still did not know, so I just gave him the address: no. 10, avenue Louise Bordes.

The road wound around the shore and began to climb. The trees made a canopy overhead, a tunnel of leaves. The driver hit the brakes and pointed. There was a steel gate and, hundreds of yards beyond it, a house. I got out and stood before the closed gate, hands on the bars, studying the lawn and fountain, the complicated roof and chimneys, the windows, the front steps, the door. I closed my eyes and could actually feel the warm air turning into a groove, the lyrics drifting across the sky in cartoon bubbles. Then, just as I was about to lose myself entirely, the driver honked.“My boo-boo, monsieur,” he said.“I have you at the wrong address.”

I burned with shame as we went a quarter mile up the road. I got out timidly, but this time certain that I was in the right place. There were the street number and the nameplate. Grand houses, like racehorses, have names. Mick’s country estate was Stargroves. Elvis lived at Graceland. The house in Villefranche is Nellcôte, a mansion in the European style, with porticos, columns, and gardens. I stood with my face to the gate. It was no longer magic I felt, but yearning. I longed to go inside and poke around. As the driver shouted “Non, non,” I climbed the fence and dropped down hard on the other side. I stood there for a long time, listening for alarms and dogs. I’d read that Nellcôte had been purchased by a Russian oligarch. I pictured a goon named Boris, a cell in a provincial jail, the sheriff ’s wife serving me foie gras and Beaujolais.

I walked up the long drive, knocked on the door. Nothing. I looked around the gardens and gates, then lost courage. The driver cursed me when I got back, but in words I couldn’t understand anyway. Besides, I was proud of my transgression. That’s rock ’n’ roll, baby. And I’d gotten a lovely unobstructed view of the house. So I didn’t get inside. So what? I already had a good idea of the interior. The grand staircase, the living room, the balcony that overlooked Cap Ferrat. It had all been described to me in great detail by June Shelley, who, in those crucial months in the early seventies, served the Stones as a girl Friday. She’d been an actress and the wife of the folk legend Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, but was beached on the coast when her (second) husband spotted the ad in the International Herald Tribune. “Wanted. For English organization in the South of France, bilingual, organized woman, salary plus expenses, 25–35 years of age.”

Shelley was interviewed by Jo Bergman, the Stones’ manager, then taken to the mansion.“I confessed on the way that I didn’t know all their names,” Shelley told me.“I knew Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. But I didn’t know the others. So Jo ran them down. She said,‘Bill Wyman, bass player, Renaissance man; moody, doesn’t speak much. Charlie Watts, drummer, blah-blah-blah.’ She described them each in a few words. ‘Mick Taylor, new kid; this will be his first album with the boys. He looks like an angel with blue eyes, round face, blond hair, and worships Keith.’ When we pulled into the garden at Villa Nellcôte, I knew everyone immediately from her description. Bill, Charlie, and Mick Taylor were sitting on the steps. It was like the circus had come to town; there were people everywhere, dogs and kids, trucks, men moving things around. Jo says,‘Hi, guys, this is June, she’s going to be your new assistant.’ They nod, and we go inside.

“What a crazy wonderful house,” Shelley went on.“You went into a long hallway and there were rooms right and left. An old-fashioned kitchen and an old-fashioned study, a partially finished basement that we later fixed up so they could record.”

Nellcôte was built in the 1800s for a British admiral, who spent many melancholic years there studying the horizon through a telescope. The Germans took possession during the Second World War. According to Richards, it served as a Gestapo headquarters. The basement was the setting of unspeakable horrors, which gave the house an appropriate sheen of menace. Dominique Tarlé, a photographer who stayed in the house that summer, spoke of exploring the basement with a friend and finding“a box down there with a big swastika on it, full of injection phials. They all contained morphine. It was very old, of course, and our first reaction was,‘If Keith had found this box . . . ’ So one night we carried it to the end of the garden and threw it into the sea.”

Richards rented Nellcôte for $2,400 a week. He kept on the old staff, including an Austrian maid and a cook affectionately known as Fat Jacques, who was fired that summer for reasons too fraught and nefarious to get into. The first floor became a kind of salon, with musicians crashed in every corner. The second floor remained off-limits, the private preserve of Keith, Anita, and Marlon. Even Jagger didn’t go up.

*

The other band members were scattered across France. Bill Wyman rented a house near the sea. Charlie Watts was in the countryside. Jagger had settled in Paris, where he took on the life of the jet-set party boy. Reeling from the breakup with Marianne Faithfull, he was seen in all the gossips, whispering in the corner of every party, confiding his pain to every beautiful woman. He’d had a torrid affair with Marsha Hunt, the devastatingly beautiful black singer and model who’d become famous in the London company of Hair. That’s her, with towering Afro, on the playbill. The Stones had asked Hunt to pose for “Honky Tonk Women,” but she refused, later telling The Philadelphia Inquirer that she “did not want to look like [she’d] just been had by all the Rolling Stones.” Jagger followed with phone calls, which turned into illicit hotel meetings. In her autobiography, Hunt claims that she was the inspiration for “Brown Sugar.” In November 1970, she gave birth to Jagger’s first child, a daughter, Karis. As in a story from the Bible, this love child, at first rejected, would later become a great solace and balm for her father in his old age.

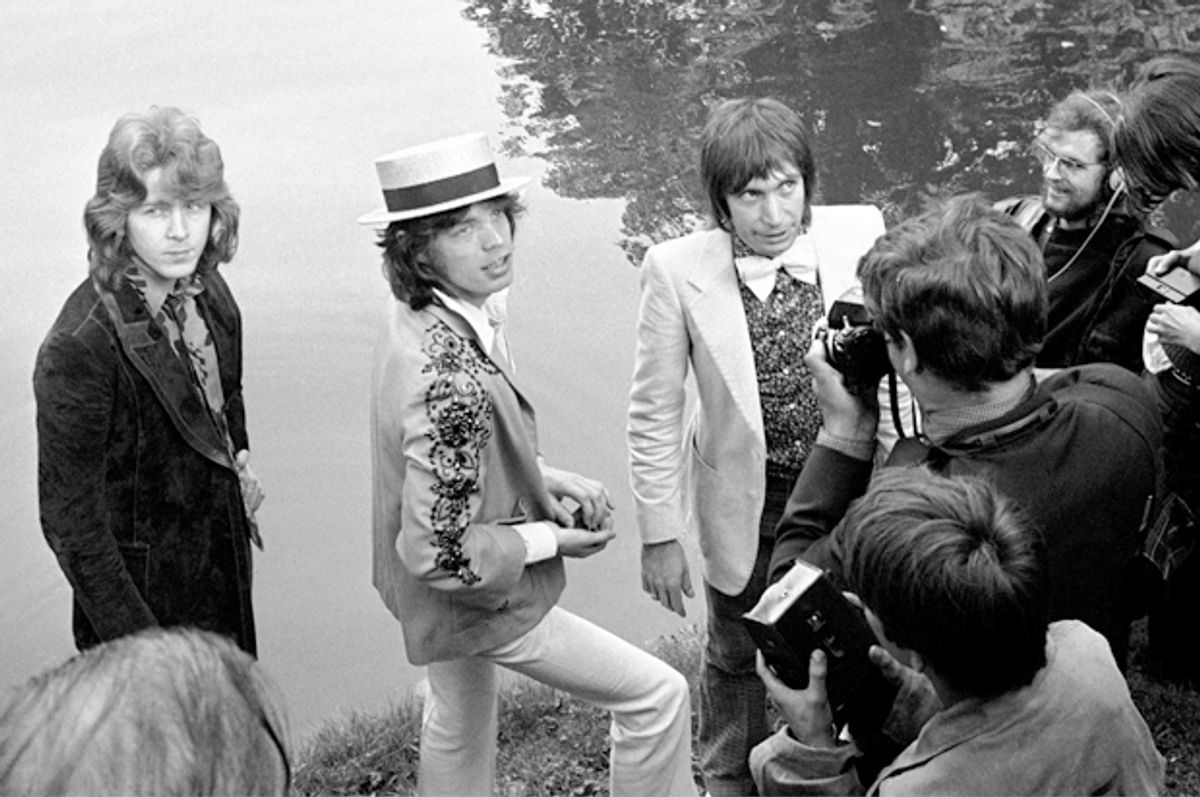

It was at a party in Paris in 1970 that Jagger met Bianca Pérez-Mora Macias, the daughter, depending on the conversation, of a plantation owner or a diplomat or a wealthy businessman from Nicaragua. She was young but refused to be fixed to an exact number. Here was a rich girl so dismissive of rock ’n’ roll that Jagger could not help but be entranced. Friends claimed that they looked like doppelgangers, twins. That Mick’s love for Bianca was a kind of self-love. Bianca got pregnant early in 1971, and just like that, Mick was sending out wedding invitations. The ceremony was in St. Tropez that spring, soon after the band arrived in France. It was the celebrity clusterfuck of the season. Helicopters buzzed the beach as the paparazzi closed in. Mick chartered a plane to fly his friends from London.“If that plane went down, you would have lost twenty years of popular music,” Anna Menzies, who worked for the Stones and was on the plane, told me. “Bobby Keys was on that flight, Jim Price, Paul McCartney with Ringo. Keith Moon. Peter Frampton, Robert Fraser, Eric Clapton. There was so much booze the plane could’ve flown without fuel!”

The theme from Love Story played as Mick and Bianca walked down the aisle. A reception was held at Café des Arts. It was a rage. Can till can’t. As on the last day. Jagger had hired a reggae band called the Rudies, but everyone got up and jammed. Jade Jagger was born a few months later. Asked to explain the baby’s name, Mick told a reporter, “Because she is very precious and quite, quite perfect.” Mick and Bianca divorced in 1979. I won’t go into that relationship further, because it just makes me sad. Suffice it to say, the marriage is credited with inspiring the great Stones song “Beast of Burden.”

*

Keith and Anita were soon back on heroin. It started with a male nurse who shot Keith up with morphine after a go-kart wreck in which Richards, racing his friend Tommy Weber at a nearby track, flipped his vehicle, chewing his back into hamburger. Appetite whetted, Keith began looking for still more relief—it’s a story hauntingly told by Robert Greenfield in Exile on Main Street: A Season in Hell with the Rolling Stones. One afternoon, Jean de Breteuil, a notorious drug dealer known, because of his suspenders, as Johnny Braces, showed up at Nellcôte. He handed Keith a woman’s compact filled with astonishingly pure heroin. Richards passed out as soon as he snorted it. When he came to, he said he wanted more—a lot more.

By June, life at the house had settled into a strange junkie rhythm. Most days began at two or three in the afternoon. Keith would wake up, yawn, stretch, hack up phlegm, swallow whiskey, reach for pills. He started with Mandrax, a downer that shoehorned him into consciousness. It was a hot summer, often above a hundred degrees. Anita was pregnant. Keith shot up before his afternoon breakfast and did not make his first appearance downstairs until five or six, a gray smack-filled ghost. He spent hours listening to music or playing. At nine, he would go to the basement to work. Like an Arab trader, he slept all morning and crossed the desert at night. He emerged at dawn. If the weather was good, everyone followed him down to the dock, where he kept a speedboat, the Mandrax II. He stood at the wheel as the coast unspooled, crossing the border into Italy, where he’d tie up at a pier and stumble up stone stairs to a bistro for eggs and kippered herring, or pancakes with strong black coffee.

Marlon was eighteen months old. Keith was far older, but a heroin addict is a baby. It’s all about bodily functions and human needs. You cry when you’re hungry. You sleep if you can. You live desperately from feeding to feeding. In this way, Keith and Marlon fell into lockstep, the addict and the kid playing on the beach.

*

Nellcôte in 1971 was like Paris in the twenties. The biggest stars and brightest lights of rock ’n’ roll came to pay tribute, get loaded, and play. People felt compelled not merely to visit but to party, measuring themselves against Keith. Like dancing with the bear, or staying up with the adults, or drinking with the corner boys. Eric Clapton got lost in the house, only to be discovered hours later, passed out with a needle in his arm. John Lennon, visiting with Yoko Ono, vomited in the hall and had to be taken away.

*

Gram Parsons turned up with his girlfriend, Gretchen. He was out of sorts, experiencing a kind of interregnum between lives. His band had broken up; his music was in a state of transition. At Nellcôte, Richards and Parsons resumed the work they’d begun years before, playing their way deep into the roots of American music. It went on for days and days, Gram, twenty-four years old, long-limbed and fine-featured but not quite handsome, sitting beside Keith on the piano bench. Their relationship was intense, mysterious. They connected spiritually as well as musically, loved each other sober and loved each other high. “We’d come down off the stuff and sit at a piano for three days in agony, just trying to take our minds off it, arguing about whether the chord change on ‘I Fall to Pieces’ should be a minor or a major,” Richards said later. If you have one friend like that in your entire life, you’re lucky.

History has been kind to Gram Parsons—the importance of his legacy revealed only in the fullness of time. The tone he worked on at Nellcôte with Keith, the perfect B-minor twang that can be heard on Exile on Main Street, inspired some of the great pop artists of later eras. The Jayhawks, Wilco, Beck—I hear Gram whenever I turn on my stereo. The mood was contagious. Jagger caught it like a cold. “Mick and Gram never clicked, mainly because the Stones are such a tribal thing,” Richards explained.“At the same time, Mick was listening to what Gram was doing. Mick’s got ears. Sometimes, when we were making Exile on Main Street, the three of us would be plonking away on Hank Williams songs while waiting for the rest of the band to arrive.” The country tunes that distinguish the Stones— “Dead Flowers,” “Sweet Virginia”—wouldn’t exist as they do if not for Parsons, who, like any third man, is there even when he can’t be seen.

The Stones, then in the process of signing a distribution deal with Ahmet Ertegun and Atlantic Records, needed to make a follow-up to Sticky Fingers. They’d gone into exile with several cuts in the can, leftovers from previous sessions—some recorded at Olympic, some recorded at Stargroves, Mick’s country house. France was scouted for studios, but in the end, unable to find a place that could accommodate Keith’s junkie needs, they decided to record at Nellcôte. Sidemen, engineers, and producers began turning up in June 1971. Ian Stewart drove the Stones’ mobile unit—a recording studio built in the back of a truck—over from England. Parked in the driveway, it was connected via snaking cables to the cellar, which had been insulated, amped, and otherwise made ready, though it was an awkward space. “[The cellar] had been a torture chamber during World War II,” sound engineer Andy Johns told Goldmine magazine.“I didn’t notice until we’d been there for a while that the floor heating vents in the hallway were shaped like swastikas. Gold swastikas. And I said to Keith, ‘ What the fuck is that?’ ‘Oh, I never told you? This was [Gestapo] headquarters.’”

The cellar was a honeycomb of enclosures. As the sessions progressed, the musicians spread out in search of the best sound. In the end, each was like a monk in a cell, connected by technology. Richards and Wyman were in one room, but Watts was by himself and Taylor was under the stairs. Pianist Nicky Hopkins was at the end of one hall and the brass section was at the end of another. “It was a catacomb,” sax player Bobby Keys told me, “dark and creepy. Me and Jim Price—Jim played trumpet—set up far away from the other guys. We couldn’t see anyone. It was fucked up, man.”

Together and alone—the human condition.

The real work began in July. Historians mark it as July 6, but it was messier than that. There was no clean beginning to Exile, or end. It never stopped and never started, but simply emerged out of the everyday routine. It was punishingly hot in the cellar. The musicians played without shirts or shoes. Among the famous images of the sessions is Bobby Keys in a bathing suit, blasting away on his sax. The names of the songs—“Ventilator Blues,”“Turd on the Run”—were inspired by the conditions, as was the album’s working title: Tropical Disease. The Stones might hone a single song for several nights. Some of the best—“Let It Loose,”“Soul Survivor”—emerged from a free-for-all, a seemingly pointless jam, out of which, after hours of nothing much, a melody would appear, shining and new. On outtakes, you can hear Jagger quieting everyone at the key moment: “All right, all right, here we go.” As in life, the music came faster than the words. Now and then, Jagger stood before a microphone, grunting as the groove took shape—vowel sounds that slowly formed into phrases. On one occasion, they employed a modernist technique, the cutout method used by William S. Burroughs. Richards clipped bits of text from newspapers and dropped them into a hat. Selecting at random, Jagger and Richards assembled the lyric of “Casino Boogie”:

Dietrich movies

close up boogies

The record came into focus the same way: slowly, over weeks, along a path determined by metaphysical forces, chaos, noise, and beauty netted via a never-to-be-repeated process. They called it Exile on Main Street—Main Street being a pet name for the French Riviera as well as an invocation of that small-town American nowhere that gave the world all this music.

Excerpted from the Book "The Sun & the Moon & the Rolling Stones" by Rich Cohen. Copyright © 2016 by Tough Jews, Inc. Published by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Shares