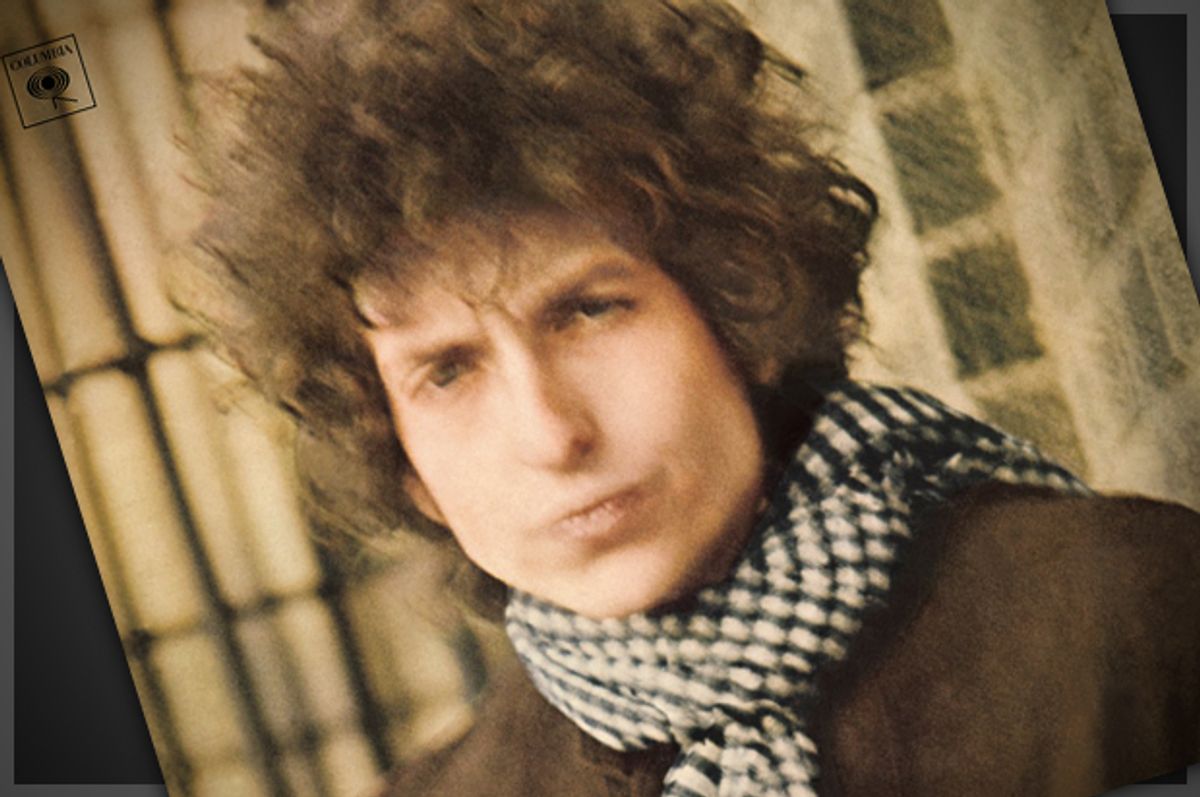

Fifty years ago today, a week before he turned 25, Bob Dylan’s album “Blonde on Blonde” was released. (On the same day as The Beach Boys’ legendary LP “Pet Sounds,” a cock-a-hoop day in music history.) For 42 of those years, since I was six, I’ve been listening to the album and being inspired by it to create art of my own, namely painting and writing. As a feminist, I’m conflicted about my devotion to Dylan and to this album and its damaging portrayal of women, a theme that runs through his body of work.

Of course, Dylan is a legendary influence on artists across genres. He is also an artist who has obviously been directly and vastly influenced by other artists from every realm. Fittingly, his own artistic influences are a frequent subject of his work, in myriad songs including “Song to Woody” for Woody Guthrie. In his essay, “The Ecstasy of Influence,” Jonathan Lethem writes, “Appropriation has always played a key role in Dylan’s music.” Dylan borrows heavily from everyone from Dylan Thomas to Charlie Chaplin to Guthrie. The gorgeous weight of the artists who have gone before him is evident in his oeuvre.

Also evident is Dylan’s sexism. Women are rarely represented in the musical or production staff on Dylan’s albums. Sexist imagery prevails and there is a frequent casting of women who have done a man wrong. Most often, his work tends to cast women into narrow tropes and roles. Marion Meade in The New York Times describes his “Just Like A Woman” from “Blonde on Blonde” by saying, "there's no more complete catalogue of sexist slurs," and goes on to note that he “defines women's natural traits as greed, hypocrisy, whining and hysteria." Sorry, Bob—a passing reference to Erica Jong in a 1997 track doesn’t undue a lifetime of woman as object, woman as crying mess, woman as fashion model, woman as sweetheart in need of a kitchen, woman as child, woman as vixen in your songs. What does it mean for a feminist like me to have one of her great artistic influences be such a sexist in so much of his work?

I’m a lifelong feminist, sporting an “ERA YES” button on my book bag at the same time I started listening to “Blonde on Blonde.” But despite Dylan’s treatment of women in so much of his work, I’ve always been a fan, and have always been inspired by his songs, despite the sexism to be found there. Is it wrong for me to be such a devotee? Yes, no, maybe — I could argue all three positions. Regardless, I am.

Dylan’s art moves me and transforms how I experience myself, the world and my own work. Are women able to find sustained inspiration in male artists in ways that men rarely seem to find similar inspiration in women’s work? A joke among my writer friends is that every time the social media meme, “List the 15 authors who have most influenced you” goes around, every cisgender, straight white man we know lists a dozen cisgender, straight, white men — and adds Toni Morrison, Flannery O’Connor and James Baldwin, “for diversity.” Sometimes, if the men are the evolved types who went to college at, say, Hampshire or Vassar, they toss in a Joan Didion or a Susan Sontag. And then they tell us about it, and the women’s studies course they took in 1989. Sometimes they tell us without mentioning the professor’s looks. Sometimes.

But sexism and exclusion are not a joke, and lack of intersectionality and under-representation of women and people of color in every realm of art and literature is a crisis that has been well-documented. People and groups like Alison Bechdel, VIDA, We Need Diverse Books and the Feminist Art Project have been fighting against such exclusions. Yet, I keep listening to Bob. He’s turning 75 next week, and I’ll be 50 myself in a couple of years, and tonight I’ll be staying here with him, on repeat — and buying tickets to see him for the 25th time.

I’m not Bob’s only feminist fan, of course. Is this acceptance of sexism — even by feminist women like myself — part of what perpetuates it?

It’s been important to me to have both male and female artistic influences. Zora Neale Hurston, Grace Hartigan, James Baldwin, John Irving, and Adrienne Rich, along with Dylan, are some of my major ones. Or course, I believe men should be influenced not only by men, but by great women and gender non-conforming artists as well. I hold that a broadly inclusive array of models makes all of our work better. I believe that feminist models serve us all well.

At the same time, I also love Aaron Sorkin’s work — and let me tell you, we need to stop saying, “he has a woman problem.” He does, but it has a specific name. Aaron Sorkin’s woman problem is sexism. I still receive beautiful, sprawling inspiration from his work — much like I do from Dylan's. I gain a renewed hope in a better tomorrow from “West Wing,” a richer understanding of how artists create from “Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip” and an idea that we the people have the power to change the world from “The Newsroom.” I should forsake him, and Dylan, and Philip Roth — despite my love of the fidelity to some sexual truth in his novels — for the sexism in their work. Yet I don’t. Their art has had the ability to reach me, and that trumps sexism to me. I love it too much to let it go. And yet, that’s my own double standard — if I found a body of work to be racist or homophobic, I’d abandon the artist.

Yes, I am being imperfect in my feminism, as most of us are. Yet I disagree with the current zeitgeist that that’s OK — I think we should all aim higher and not excuse ourselves by saying, “This is bad, I shouldn’t do it, but I’m going to anyway.” Sexism is not an occasional pasta dish or the once-a-year cigar. It’s a pervasive scourge that damages all of us, that directly maims the lives of women and leaves us all in chains. I don’t think it’s OK to whisk away a total buy-in with “but I like it!” I also accept that I’m a human being, and deeply flawed, and that one of my flaws is my imperfect feminism, which includes my love of Dylan.

I started with Dylan’s “Self-Portrait” album. I took my painting in preschool somewhat seriously — as seriously as you can at age 4 and 5 — with a palette I mixed to match Dylan’s painting on the cover of his LP. At that early age, I followed his lead both in creation and imitation and felt the inexorable link between the two. At six, I started listening to “Blonde on Blonde” — unfolding the double album and studying the stretched-out portrait of Bob himself revealed. I slept with both albums propped up next to the wall in bed with me. In Catholic school, I heard the stories of the saints and martyrs for the faith being stoned to death. I though “Blonde on Blonde”’s “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” was about that kind of stoned, and I hated it. I liked some of the other songs and didn’t like some, but “Visions of Johanna” had me at the first chord. From the first time I heard that sweet A major that opens the song, I was smote.

Fast forward many years: Last month I was in residency at the Millay Colony for the Arts, on the estate of Edna St. Vincent Millay. I spent a lot of my time with Keith Wilson, a poet who lived next door, and visual artist Roeya Amigh across the hall. The three of us would stay up all night working and would often meet for a 3 a.m. coffee break. Roeya, who is from Iran, told stories of the revolution and what it has meant for women. She told us of leaving Iran to come to Boston to study with John Walker, whose paintings she had so admired from afar. Keith showed me former Millay colonist Leonard Cohen’s name carved in the doorjamb of his studio, and we made rubbings. I started to take myself so much more seriously as a writer because of the other artists who’d come before me.

Checking the doorways and calling out the big names is a pastime at Millay. Being part of the history of the storied Millay — both the poet and the colony — is an uplifting gift. We residents felt the weight, the tradition, of what those earlier artists had done, given us. The walls covered with their paintings and sketches, the bookshelves crammed with their volumes. We all want to tap into some ancient river of creation — visual art mixing with poetry mixing with composing mixing with writing. Elizabeth Riggle in her studio, painting. Ben Irwin in his, composing. Racquel Goodison writing. Millay herself buried down the lane. Gary Krist and LeVan D. Hawkins and Lacy Johnson and Nick Flynn and Kelle Groom’s names carved into the wood. This is art, we are artists, is a vibe that hangs in the air, leading residents to work long days and nights on their craft. You are surrounded there by the notion that all of these artists came before you, and all of these others will come after. This is what lives on, when we are long gone — this practice, this creating. Life is short, but art is long.

That’s what Dylan’s “Blonde on Blonde” song “Visions of Johanna” is to me, and maybe it’s why I still love Dylan so much. It’s the musical embodiment of the idea that all these other artists — past and present — swirl around us and feed us, inspiring us to give our art to the world and in turn fuel the next generation.

Anyone who says they are giving the meaning of any given Dylan song is full of shit, unless they are quoting what Dylan has said what the song is about, as he almost never does. Yet there’s no shortage of “definitive” explanations of Dylan songs out there, almost all by men, because usually it’s men who write about Dylan. Women writing about Dylan is a rarity in a world where there is a lot of writing about Dylan. Women writers make up only about 20 percent of “The Oxford Companion to Bob Dylan” contributors, and that’s a high oddity. Rolling Stone has published roughly nine-billion major pieces on Dylan and interviews with him over the yeas, and one is hard pressed to find a dozen of them written by women. In fact, I couldn’t find a dozen by women, but then, I gave up after a few hours of trying. (I’m sure 87,543 of you will now point out all the women who did write about Dylan in Rolling Stone and how I’m just a dumb girl and this is why chicks shouldn’t write about rock and roll. Yeah, just like a woman.)

So to be clear, I offer no definitive explanation about the meaning of “Visions of Johanna,” but to me the song is about the beautiful weight of past creations that artists carry. “Lights flicker from the opposite loft,” Dylan sings in the opening verse, and that’s all about the elusive nature of inspiration. It’s there, it’s not there, we want it but it can’t be the only thing, we can illuminate our own way with it, but only so far. We have to do our own thing, too. “The country music station plays soft but there’s nothing, really nothing to turn off,” Dylan warbles. He grew up listening to country music on the AM radio in Hibbing, Minnesota, and he still hears those masters from the wayback in his head, even when the radio is not on.

And those “visions of Johanna” are? Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings. It was Van Gogh’s sister-in-law Johanna Bonger who had the vision to make him famous after his death and the death of her husband, Vincent’s brother Theo. She arranged shows and deals with famous art dealers. She published his letters. Dylan’s songs references Van Gogh’s art, and in the larger sense, Van Gogh as meta-inspirational artist. It’s these visions of Johanna — literally, Van Gogh’s paintings, and metaphorically, the ancient greats — who keep him up past the dawn, just as Van Gogh himself stayed up past the dawn each night creating his masterpieces.

I didn’t have all that figured out at six, of course — I was a freaky kid, but not that freaky — but even as a first grader, Dylan translated the big for me, spoke to me of the effect of art on later artists. It was, and is, powerful. Life-shaping.

I still love “Blonde on Blonde” — its sound, its energy, its place in the world. I don’t listen to “Just Like a Woman” anymore, because “she takes just like a woman / she makes love just like a woman / but she breaks just like a little girl” conjures a woman whom Dylan isn’t really seeing, so I don’t want to hear about her. Women are so much more complex than that, and the song pisses me off. But overall, the album is vast and true, and when Dylan describes the sound of it as “that thin, that wild mercury sound” we nod. Yes. I read or heard it described once as an album that sounds like three o’clock in the morning feels. Yes. How it feels boozy, on fine liquor, with the promise of sublime sex just as the coal of night fades into aching blue wonder of early morning. That’s the sound. And I remain mesmerized by Johanna. I’ll be listening to that song until I die.

Four decades after I started listening — now that I am a working writer with the challenges that presents — “Visions of Johanna” is more resonant to me than ever. It sings of my everyday, of the work and influences I carry with me. “Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial,” a looming lyric from the middle of the song, speaks of the art we memorialize and value, as well as the way art is harshly judged, and how that’s how our culture decides what lives on ad infinitum. Everything about art in our culture might be in that line. For me, it evokes the feeling of trying to balance taking my own work seriously, pitted against the knowledge that all this big, great, important art already exists, so why bother? In the face of that, what does my work mean, if anything? Maybe nothing, but if art is what remains, I’d better make some. Infinity is going up on trial. If I want to compete, I better be good. The lyric is an invocation to greatness.

Dylan is not an imperfect feminist — he’s not a feminist. His work is overtly sexist, and often, and yet he gives me, and so many others, the world. Calls us to create. So I keep listening, imperfect feminist that I am. I’m celebrating “Blonde on Blonde” today. I want it not to be sexist, and I want Dylan to be at least an imperfect feminist, like me, and he’s not. But he’s the one who taught me that in this world that is, I hope, hurtling away from the divisive marker of gender, in the future, “these visions of Johanna” — art, man — will be “now all that remain.”

Shares