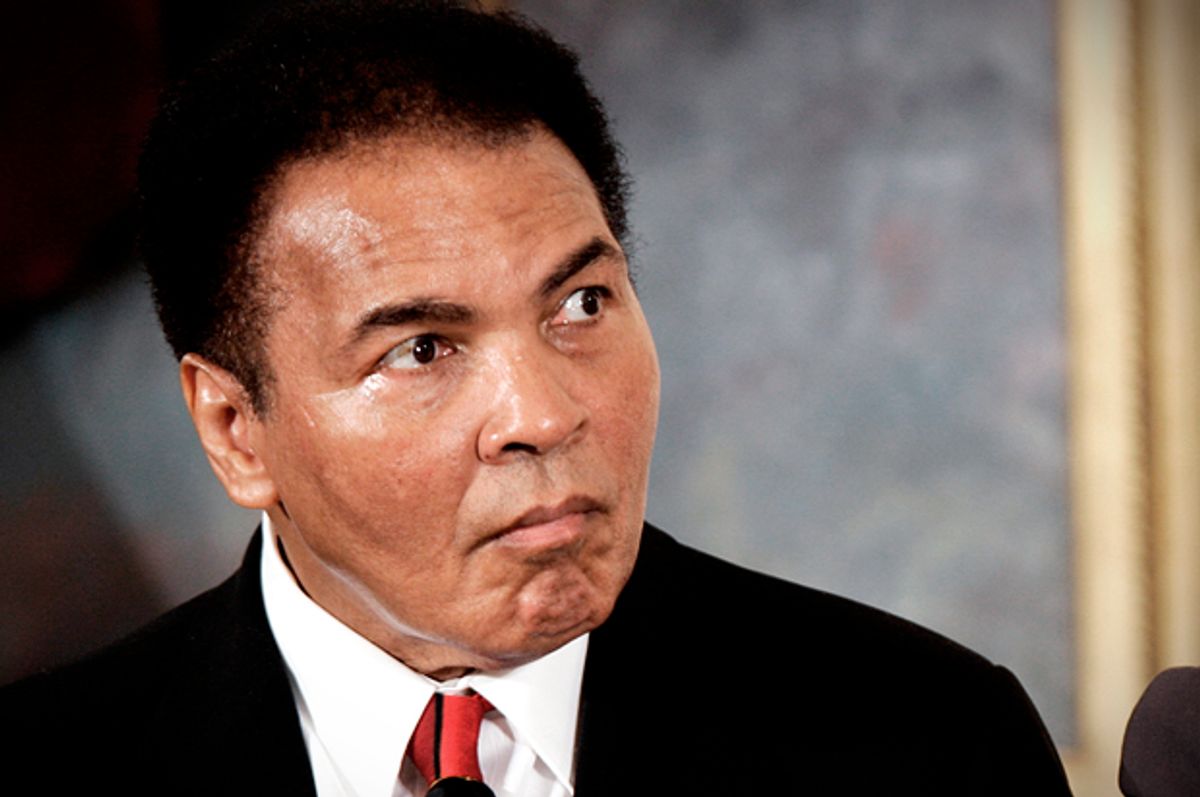

Muhammad Ali became human in 1996. On this summer night in Atlanta, the manifestations of a disease diagnosed twelve years before were now evident. The man who once routed Superman on the pages of a comic book was now displaying the ravaging effects of his kryptonite: Parkinson’s disease. It had reduced his outsized charisma to perpetual silence and his quick fists to tremors. With his body and arm trembling uncontrollably, Ali reached out to light the Olympic cauldron. As he attempted to summon control over a nervous system gone awry, the world watched him comport himself with a dignity not often seen in the face of such a chronic and transforming illness. And as the cauldron was inevitably lit, our collective sadness was eclipsed by an overwhelming joy. Despite his frailties, Ali was once again the greatest.

As Muhammad Ali is exalted in the wake of his death, we are reminded that his most defining challenges were encountered outside of the boxing ring. Despite being a pugilist, the names Sonny Liston and George Foreman seem like mere footnotes in his story, for he was animated greatly by the pressing issues of his time and transcended the confines of sports. He wasn’t afflicted with the myopia of personal brand promotion that plagues many athletes and his engagement with the inequities and contradictions of his world remains unprecedented even today. Much has been rightfully written and said about his principled defiance, his steadfast commitment to truth, and how he was a champion for the dispossessed and downtrodden.

Ali’s vitality, wit, and loquaciousness were his hallmarks and provide the most enduring memories. Even before his Parkinson’s disease was diagnosed in 1984, many of the faculties that made this beloved Ali possible began to gradually erode. Starting in 1978, his speech began to slur, and a few years later, saliva drooled from his mouth and a hand tremor was present. When asked by Bryant Gumbel in a 1991 television interview if he had any reservations about making public appearances in this transformed physical state, he replied: “I realize my pride would make me say no, but it scares me to think I’m too proud to come on this show because of my condition.” Soon there was no remnant left of a floating butterfly or stinging bee. Yet he refused to retreat into the shadows as the disease progressed within him and remained a public figure despite being stripped of everything he was once celebrated for. He remained unbowed even as his fight with Parkinson’s entered the final round.

Parkinson’s disease is a common ailment of the brain that affects its ability to control movement. Nerve cells (neurons) in the brain produce a chemical called dopamine, which is essential to control movement. Once these cells slowly degenerate in Parkinson’s disease and lose their ability to make dopamine, individuals diagnosed will develop tremors, move slowly, and their muscles and facial expressions stiffen or become rigid. As the body’s supply of dopamine dries up, the severity of a patient’s symptoms will increase. The condition affects 7 to 10 million people worldwide. Though a cure remains elusive and no treatment can currently halt the disease’s progression, medications exist to alleviate the symptoms associated. Patients are thus left grappling with a chronic, debilitating illness that can also affect cognition. And so as time passed, Ali was left a shell of his former self, with many of his most treasured attributes lost to a disease that is often readily linked to his storied boxing career.

Punches to the brain are a bad thing, but the association with Ali’s Parkinson’s appears to be murky. Dr. Michael Okun, who is medical director of the National Parkinson Association, states that Ali’s specific presentation “has all the hallmarks of Parkinson disease, what we call idiopathic or ‘regular garden variety’ Parkinson disease.” Though research remains conflicted on the topic, Okun’s comment essentially exonerates boxing’s role in Ali’s decline. However, the NFL’s recent acceptance that repeated head blows can cause neurological disease, specifically chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), heightens the suspicion that some degree of impairment, whether related to Parkinson’s or not, must have occurred from the punches of Frazier and Foreman. The scope of the brutality was best appreciated in 1977 when Earnie Sanders savaged Ali and Madison Square Garden’s matchmaker refused to schedule the three-time heavyweight champion to fight there again.

The courage that propelled his being would remain insulated from the countless punches and Parkinson’s crippling effects. He emerged in 1996 for the Atlanta Olympics with his greatest vulnerability on display for a global audience, yet the indomitable spirit that agitated for civil rights and remained defiant against a war in Vietnam remained. As the man staggered forward despite the neurons that had betrayed him, his greatness finally became relatable and accessible to the mortals that watched. In this moment, he taught us to persist with dignity and grace in spite of our wounds, physical or metaphorical, and galvanized millions who suffer from chronic and debilitating disease. Strength emanated from his greatest weakness. We realized the virtue in such an existence with every public appearance Ali continued to make over the years. This was how to knockout life.

Shares