Before June 2, when Brock Turner was sentenced for sexually assaulting a woman behind a dumpster following a Stanford fraternity party, his victim, given the pseudonym “Emily Doe” to protect her identity, had been represented by the media as the anonymous “unconscious, intoxicated woman.” But in a 12-page impact statement she read to the court, she shared her story in unflinching detail, brought light to some of the struggles faced by rape survivors in the wake of their attack and denounced a culture of victim blaming. After Turner received a pittance of a sentence–a six-month stint in a county jail, half of which he won’t even serve–Doe’s statement was published in full by Katie Baker at Buzzfeed and has since gone viral. For many of the millions of people who have read it, Emily Doe has been transformed from a random, faceless victim into a friend, a sister, a daughter, or their own reflection.

By bringing her impact statement to the public, Emily Doe has done something nothing short of incredible. She’s forced America to start a conversation it hadn’t quite been ready for, even after a year in which high-profile sexual violence stories, including those of the dozens of women speaking out against Bill Cosby and pop-singer Kesha’s allegations against producer Dr. Luke, among others, have been widely discussed in the news and social discourse, and in a time where young women are increasingly calling out those who perpetuate sexism, misogyny and gender-based violence in public forums. After all, it is still a culture in which real discussions about rape are rare but images of sexual violence are everywhere, in which creepshots and revenge porn are things women legitimately need to worry about, and in which the rights of women to make decisions over their medical health and family planning are being increasingly threatened and legislated by governing bodies. If general social conscience is in turmoil, Emily Doe has circumvented it by grabbing individual hearts. Still, even though millions have read her words and have expressed their compassion and support, taking steps toward educating people to better understand the impact rape can have on the individual, it is still only a baby step forward in the grand scheme of progress.

Aside from the enormous public response over the last few weeks, both to Emily Doe’s statement and other components of the case, including a disturbingly tone-deaf letter to the court penned by Turner’s father, the only other thing that is truly remarkable about the Stanford case, which could otherwise get lost in a sea of similar campus rape stories, is that as short and unjust as Turner’s sentence may be, in a country where only 6 out of 1000 rapists (white college athlete or otherwise), ever serve a day in prison, it is a small miracle he will serve any time at all.

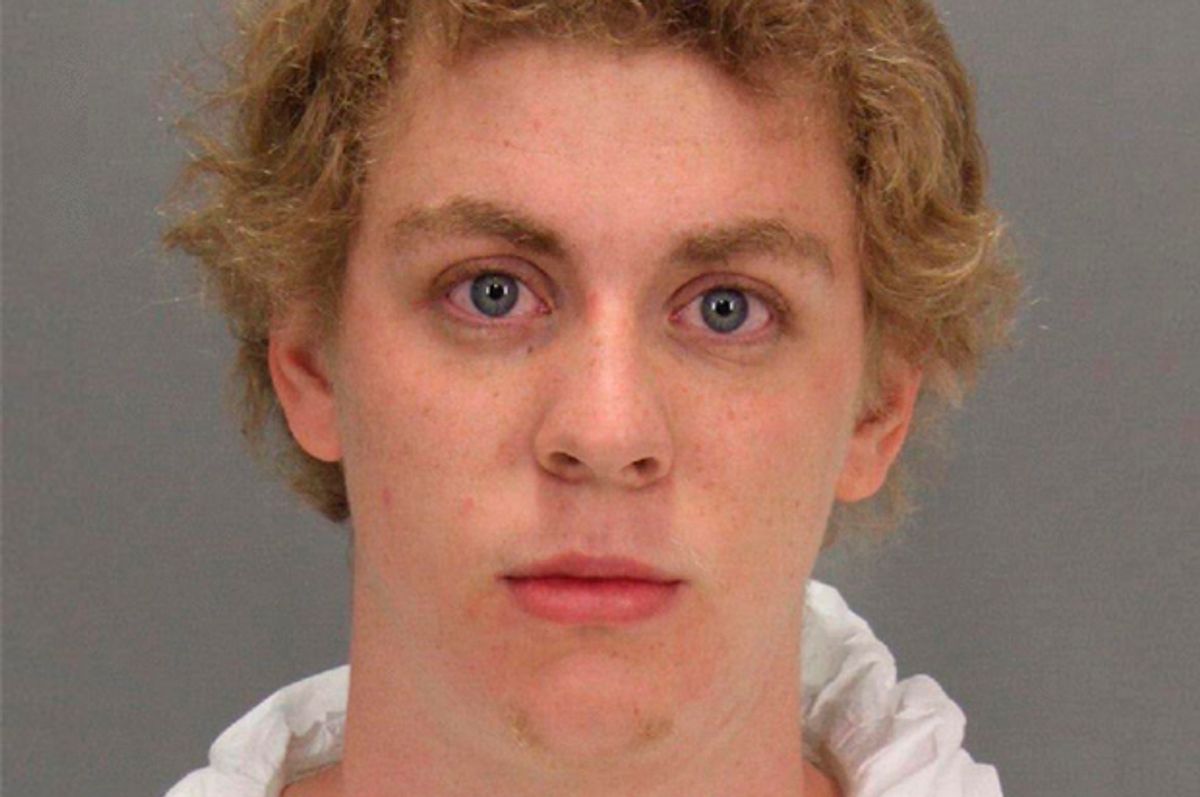

Much of the outcry has revolved around how Turner’s whiteness, status as a prized athlete, and relative affluence may have influenced Judge Aaron Persky’s decision to hand him such an anemic sentence, and rightly so. Ours is a justice system fraught with a long and storied history of racism and classism. The same goes for our media, that demonstrated this time and time again in its representation of Turner compared to the negative depictions of many black men accused of sexual or non-violent crimes, for example running a photo of him smiling in a jacket and tie versus his mug shot.

This critical look at Turner’s race and privilege and how it impacted the events leading up to and the outcome of his trial is essential, but it is just part of the picture of how privilege plays out in sexual assault cases. Despite the passionate support for Emily Doe over the past few weeks and months our society is still very much skewed against victims of sexual assault, no matter who attacked them, and bias can enter the justice process under various guises and forms. Therefore, conversations about privilege and sexual violence should ultimately start with them.

Emily Doe highlights some of these biases several times throughout her statement, for example how she was relegated to “unconscious, intoxicated woman,” in media coverage, which effectively cast her as being complicit in her own rape while the same articles listed Turner’s swimming accomplishments in their endnotes. Or how Turner’s lawyer tore her apart on the witness stand, trying to paint a picture of her as a wanton party girl with an alcohol problem and Turner as a good boy led astray by campus drinking culture and whose version of the events was more reliable than hers (despite witnesses and medical evidence that corroborated her testimony) because hey, at least he was conscious enough to remember.

But as brutal as these incidents, and the repeated traumas Emily Doe has suffered–from waking up on a hospital gurney following her attack, covered in dried blood and lacerations, to her daily struggles with PTSD–her story and the support she has gleaned from the public since it went viral touches on another elephant in the room when it comes to privilege and sexual violence. Privilege impacts the experiences of sexual assault victims, as well as those of the accused, and our society continues to allow it to happen.

Without diminishing her experience even a millimeter–no one should ever have to suffer what she has–it is important to consider how different the public response to her statement might have been had she been perceived as poor, uneducated, transgender, homeless or otherwise disenfranchised, a person of color (given the stereotypes of fraternity culture it is fair to argue that many who read her letter presume her to be white), or a sex worker. What if Brock Turner had not attacked an “unconscious, intoxicated woman” he met at the party that night, but instead had been caught raping an “unconscious, intoxicated man?” Would over five million people have taken time out of their day to read the impact statement of that person and be as openly moved by their words? Would public figures such as Vice President Joe Biden have felt compelled to respond personally?

For sexual assault victims, privilege can play out not only in how they are treated by the media, the legal system, and society at large, but also in access to resources, whether it is appropriate mental health services, time off of work to deal with medical or legal needs, the ability to move out of their home if they feel unsafe, or anything else that come up in the wake of their attack. It can affect which victims are believed and taken seriously, and which cases are given priority for investigation, though the issue of “priority” in criminal investigations is also arguably a result of overloaded, understaffed police departments. Even in states that have funds (paid into by felons during their prison sentences) reserved to compensate crime victims for some of the economic costs of their ordeal (an ambulance ride, for example), simply filing the paperwork and following up to make sure it is processed in a timely, efficient manner can be an arduous task that can take months or years to resolve and requires a victim or family member to be able to constantly advocate on their own behalf. Gender can have an impact on resources too. For example, Nathaniel Penn’s extensive coverage of the military rape crisis for GQ shined a light on how ill-equipped many agencies (including the VA) are to deal with the needs of male survivors. Needless to say, each piece of this picture can be personally and emotionally exhausting.

The intense rage over Turner’s minescule sentence is an unprecedented moment in the national discussion of sexual violence, especially when it comes to campus rape, but it’s crucial that we start to address what will happen once the buzz surrounding the story dies down. To look at the case as an isolated incident of race and class privilege, or to focus solely on campus rape sidesteps the bigger picture of injustice within the legal system and bias within our society where sexual violence is concerned. It also risks missing opportunities to help make things better for all survivors, not just those that fit the narrative of the “classic rape victim” (read: white, educated, middle-to-upper class cis-women). Even a successful effort to unseat Judge Persky won't address the fact that injustice towards rape survivors plays out across the system every day, and all the online support in the world for Emily Doe won’t scratch the surface of the issues unless that spirit is propelled into positive action.

If you’re feeling angry again, good. Now is your chance to do something about it. The issue of sexual violence in our society is way, way too important to allow it to become another “flavor of the week” in Internet chatter. And along with supporting sexual assault survivors on an individual basis, we must also take steps to make our justice system better and more accessible for anyone caught in its wheels. “Survivors understand that there is a lot of things that are out of control of a police officer or a prosecutor,” said Sharmili Majmudar, the Executive Director of Rape Victims Advocates, a non-profit group that works on behalf of hundreds of rape and sexual abuse survivors in the Chicago Metropolitan area each year. “They know the process might not end in a result they are happy with, they just want the process to unfolds in a way that is fair and respectful, and really upholds their dignity as human beings, let alone survivors of crime.”

Here are 10 ways you can help:

1. Know the laws in your state

RAINN even has an online database where you can easily access information regarding the definition of consent and sentencing policies in your state.

2. Vote

Do your research so you can make informed decisions about which candidates on your ballot can make a difference.

3. Work to educate public officials

“We often hear that judges are inadequately prepared to address sexual violence because they have [their own preconceptions], as many of us do, because we are a society that believes a lot of myths about sexual violence,” Majmudar said. “It's not about whether the judge doesn't understand the law, but understands sexual assault, trauma, and impact. There's a level of that we're not necessarily going to be able to touch, but we can do a better job educating people who are going to become judges or who are in other parts of the legal system, the police, the prosecutors as well. Issues of victim-blaming are rampant in the system.”

4. Demand faster testing of rape kits

Although rape kits, which are used to collect evidence of assault, including, potentially, the DNA of the attacker, have become crucial to achieving justice in sexual assault cases, many communities have a backlog of kits that need to be tested. “As you know, [sexual violence] cases move really slowly,” says Majmudar. “So we are following them from year to year and can really not say how soon a case is going to go from beginning to end, especially when we have cases where police are telling us that their investigation are pending the return of the evidence collection kit. In Illinois, the average evidence collection kit is taking 367 days to be processed. That's already beyond a full year at that point… This is pre-arrest, pre-charges. Having to wait that long, the process gets really delayed.”

5. Demand transparency and accountability from public universities

Press institutions to communicate about sexual violence incidents on campus and what they are doing to make it better. Also demand that incidents of rape be referred to law enforcement, rather than handled by campus disciplinary boards alone. Writing for the Washington Post, KC Johnson and Stuart Taylor Jr. argue that as unsatisfactory as the outcome of the Turner case may have been, it still proved that despite its flaws, the system works and is therefore a preferred means to seek justice rather than panels of school officials or students with little procedural experience. “Indeed, had this case been initially channeled through the school, critical evidence — including Turner’s highly incriminating statement to police — might have been lost,” they said.

6. Work with state coalitions to help impact policy

“Connect with state coalitions or local rape crisis centers on what legislative or policy agenda they have. Most state coalitions have a legislative agenda someone could be a part of that, whether that means talking to your legislatures, providing testimony, writing letters, or just encouraging other people to support it. I think that can be an important piece,” Majmudar said.

7. Support victim advocacy organizations

“There is a significant amount of research about how having support from advocates, in terms of successfully making reports and staying connected to the case in a way that is not re-traumatizing. So, basically ensuring there are resources to support rape crisis services so that we can be there for survivors,” Majmudar said. Many organizations offer direct ways to get involved through volunteering as an emergency room or court advocate, community outreach, fundraising, and more.

8. Speak out about mass incarceration

Promote efforts in your community to reduce mass incarceration and recidivism, especially by increasing opportunities for non-violent and juvenile offenders. It is arguable that the disastrous “war on drugs” and the staggering high number of Americans in and out of incarceration is part of what is clogging up public resources for victims of rape and other violent crimes. There is also the often-ignored epidemic of prison rape that affects approximately 200,000 people serving time each year, to consider as well.

9. Keep the conversation going

“We are not necessarily going to be able to incarcerate our way out of this problem, which means we really have to invest in sexual violence education and comprehensive sex-ed,” Majmudar said. “We have to do so, in developmentally-appropriate ways, starting in primary school. We can't wait until someone is 18 and a college freshman before we're having important conversations about consent and about respect.” She adds that Carl-Fredrik Arndt and Peter Jonsson, the two Swedish grad students who intervened during Emily Doe’s assault offer another reference point in the discussion. “We can now say to people, ‘if you're going to be any guy in this situation, that's who you want to be, and it is possible to step in in a way that is meaningful,’” she said.

10. Listen to survivors and support their choices

Finally, remember that justice is not defined the same way by every survivor of sexual assault. “It is important to honor the various ways that survivors define justice for themselves,” Majmudar said. “For some survivors having someone locked away for life is not their definition of justice. We need to make more options available for survivors and support them in choosing them if we can.”

Shares