In America’s slow and steady move from a literary culture to an audio-visual culture with literary accessories like Twitter feeds and text messages, much of the nation has lost its appreciation for eloquence. Language is communicative, but in political or artistic context, it is also aspirational. The poetic grandeur of Lincoln’s “House Divided” address to the Illinois State Legislature, the sermonic beauty of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and the anthemic triumph of Kennedy’s inaugural address map a future of better and boundless possibility not merely with content, but with style of articulation. If Marshall McLuhan was right with his now clichéd proclamation that the “medium is the message,” it is not too damnable a distortion to apply his theory to rhetoric itself, and make the determination that political leaders have a message, and are able to delineate a vision of the world, not only with what they say, but the way in which they choose to say it.

In a devolution that puts to bed fanciful notions of progress, America has transitioned from eight years of one its most elegant and intelligent presidents to consideration of a man who, according to several studies, speaks at a fifth grade level. The right wing, often unable to recognize the sound of a sophisticated voice, consistently mocks Barack Obama for his use of a teleprompter, as if he is the first politician to give prepared remarks or that the teleprompter itself, as opposed to words printed on paper, is somehow worthy of ridicule. To actually gain insight into the rhetorical gifts of the current president, along with the insipid ramblings the Republican nominee for president, Americans should turn to the written word.

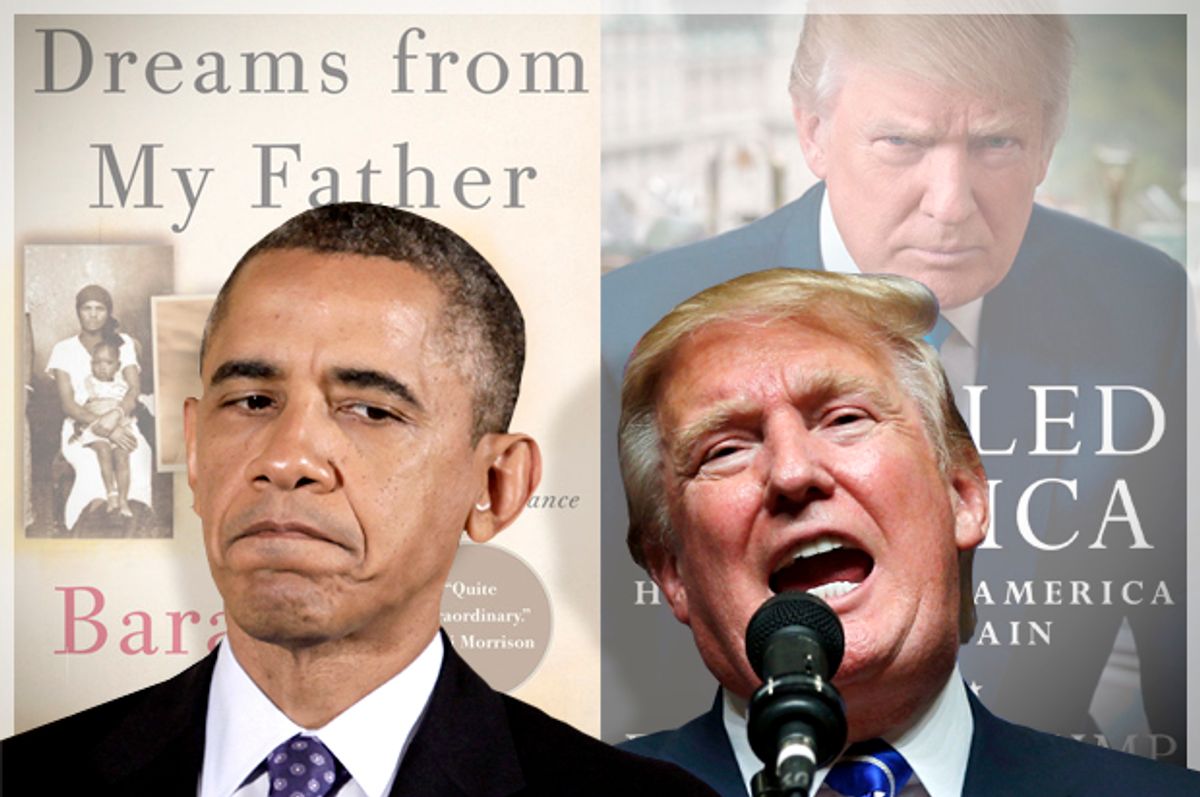

Barack Obama began his memoir "Dreams from My Father" with the following paragraph:

A few months after my twenty-first birthday, a stranger called to give me the news. I was living in New York at the time, on Ninety-fourth between Second and First, part of that unnamed, shifting border between East Harlem and the rest of Manhattan. It was an uninviting block, treeless and barren, lined with soot-colored walk-ups that cast heavy shadows for most of the day. The apartment was small, with slanting floors and irregular heat and a buzzer downstairs that didn’t work, so that visitors had to call ahead from a pay phone at the corner gas station, where a black Doberman the size of a wolf paced through the night in vigilant patrol, its jaws clamped around an empty beer bottle.

The paragraph reads like a passage from a fine novel. It describes a world of complexity and irony – not fit for simple explanations or prescriptions – but one where questions outnumber answers, and individuals must engage in the art of self-discovery, always turbulent and painful, to even hope to find clues in the intractable mysteries of life. It is literature. "Dreams from My Father" follows in similar style, and joins the tradition of memoir and novel attached to coming of age, formative experience, and individualistic transformation.

Donald Trump begins his latest book, charmingly titled "Crippled America," with the following “sentences”:

Some readers may be wondering why the picture we used on the cover of this book is so angry and so mean looking. I had some beautiful pictures taken in which I had a big smile on my face. I looked happy, I looked content, I looked like a very nice person, which in theory I am. My family loved those pictures and wanted me to use one of them. The photographer did a great job. But I decided it wasn’t appropriate. In this book we’re talking about Crippled America—that’s a tough title. Unfortunately, there’s very little that’s nice about it. Hence, the picture on the cover. So I wanted a picture where I wasn’t happy, a picture that reflected the anger and unhappiness that I feel, rather than joy. There’s nothing to be joyful about. Because we are not in a joyous situation right now. We’re in a situation where we have to go back to work to make America great again. All of us. That’s why I’ve written this book. People say that I have self-confidence. Who knows? When I began speaking out, I was a realist. I knew the relentless and incompetent naysayers of the status quo would anxiously line up against me, and they have.

The world Trump depicts is simple, and for the simple-minded. The state of the country, and the world, is static and categorical. It is bad. It is terrible. He can make it good. Only he can make it good. He will make it great (the style is contagious).

Trump’s appeal is an indictment of the public education system of America, and the American cultivation of an anti-intellectual culture suspicious of eloquence and learnedness. It dates back to the 1950s when many American voters mocked and derided Adlai Stevenson as an “egghead,” as if having an educational pedigree was a liability. It is important to remember that Stevenson’s populist opponent was Dwight Eisenhower, a former general whose rhetoric reads like Shakespeare in comparison to the childlike incoherence of the average Trump speech.

Many defenders of Trump’s blather claim that he is speaking directly to his poorly educated constituency in a language that they can understand and appreciate. In that sense, Trump sympathizers will claim, it is a truly democratic act of charity for a man who has an Ivy League education to communicate, by design or default, with an elementary school style. Those who make this argument confuse pandering with leadership. Leaders should challenge, not coddle their audiences.

Trump’s dialect is deceptive, because it implies that complicated institutions need only the right authority figure to work smoothly in favor of the general public, and that the world is not always at contradiction, but that it is rather straightforward – like a formulaic television series. The continual debasement of language in American culture played right into Trump’s miniature hands. To track the preferred method of Internet argument from the popularity of blogs to the ubiquity of Twitter is to monitor a culture increasingly accustomed to short and simple explanations and rebuttals.

The rhetoric of Barack Obama – whether in oratorical high moments like the “Yes We Can” speech, the address at the memorial for the victims of the 2011 Tucson massacre, or the eulogy for Beau Biden – illustrates a “heretic against the religion of certainty,” as he called himself in "Dreams from My Father." Obama’s evasion of category – in word and deed – frustrates both admirers and adversaries alike. His rhetoric speaks of a world in need of investigation, and a world in which workmanlike dedication to rational and thoughtful reform can likely lead to improvements, but there is no guarantee. Whether or not his policies followed through on his rhetoric is a debate that will long take place among historians and social critics, but one of the most important functions of the presidency is not just as commander-in-chief, but what one book calls “communicator-in-chief.”

As communicator-in-chief, Barack Obama has attempted to elevate the discourse throughout a culture committed to lowering every standard of self-expression. Trump embraces the decline, and even enables people to feel good about becoming part of it. A significant part of the nearly universal contempt for “elites” in American politics is a discomfort with illustrations of intelligence. Rather than looking at the president as a person to whom people should aspire, too many Americans look at the president, as they did with George W. Bush, as someone they would “like to have a beer with.” Obama seems like a much more appealing barroom companion than Bush or Trump, but his language does not massage the insecurities of those who would make excuses for their ignorance. One need not graduate from Harvard Law or the Wharton School of Finance to claim intelligence or culture, but one needs to practice the discipline of intellectual rigor. Eloquent language emphasizes the necessity and nobility of that discipline, while ignorant language encourages a shallow culture of philistine complacency.

Oliver Jones, a brilliant Oxford graduate and British writer, offers an analysis, stunning in its depth and clarity, of Donald Trump in his new book, "Donald Trump: The Rhetoric." The short exploration of Trump’s triumph manages to entertain, even as it terrifies. Jones writes that Trump is the “equivalent of an untrained actor stunning audiences with his artless sincerity.” He “speaks to a theoretical section of the electorate that is not politically aware, does not care too much about policy, has a simplistic view of politics and is unsympathetic towards political process and toward compromise.”

Trump’s style and message, in this sense above all others, contrasts with Obama, who always delivers his position with a package constructed out of the messy fibers of democracy – a language that underscores the complexity of the political process and necessity of ideological compromise.

The dichotomy and disparity separating the rhetoric of Trump and Obama is not merely contemporary. It flashes far back into the origins of democratic governance and balance of powers, always at odds against the tyranny of monarchy and the nightmare of mob rule. As Jones puts it, “Trump replaced the political virtues of Aristotle, Plato, and the founding fathers – sagacity and wisdom – with the virtues of the action movie hero: masculine indifference, anti-intellectualism, ‘guts’, and a steady source of one-line put downs.”

American rhetoric has always acted as host to a larger conflict of perceptive values. It is the language of the cheap adman, the conniving televangelist, and the demagogic politico. It is also the language of Jefferson, Lincoln, King, and Eleanor Roosevelt – the language of Whitman, Ellison, Dickinson, and Morrison.

Although Hillary Clinton lacks Obama’s sense of poetry and his inspired gift for oratory, she does, at least, communicate in the language of policy. Her language (and again, policy is a separate matter) communicates the challenge of the political process. It is difficult work to legislate and govern, and it requires an acrobatic mind able to adjust and adapt in an attempt to balance multiple tasks, duties and contradictions all at the same time.

Jesse Jackson, who has given some of the greatest speeches in political convention history, once explained that leaders should elevate people with their language, not speak down to them or even meet them where they are at. As much of the American public becomes politically illiterate, it is important to have a leader who will confront that illiteracy, and advantageously exercise the bully pulpit to enlarge the mind of the voter, and expand the possibilities of political understanding.

Obama, with his books, speeches and public persona, made a valiant effort in the art of civility and sophistication. Oliver Jones writes that Trump has mastered a message of “down-to-earth vulgarity.” He is the pop-cultural candidate – the candidate of the Kardashians, the mindless tweet, and the incoherent celebrity rant on social media. Far from offering the service of elevation, he can only speak down to people, and bring them, along with American political culture, down to the depths of his rhetorical gutter.

Shares