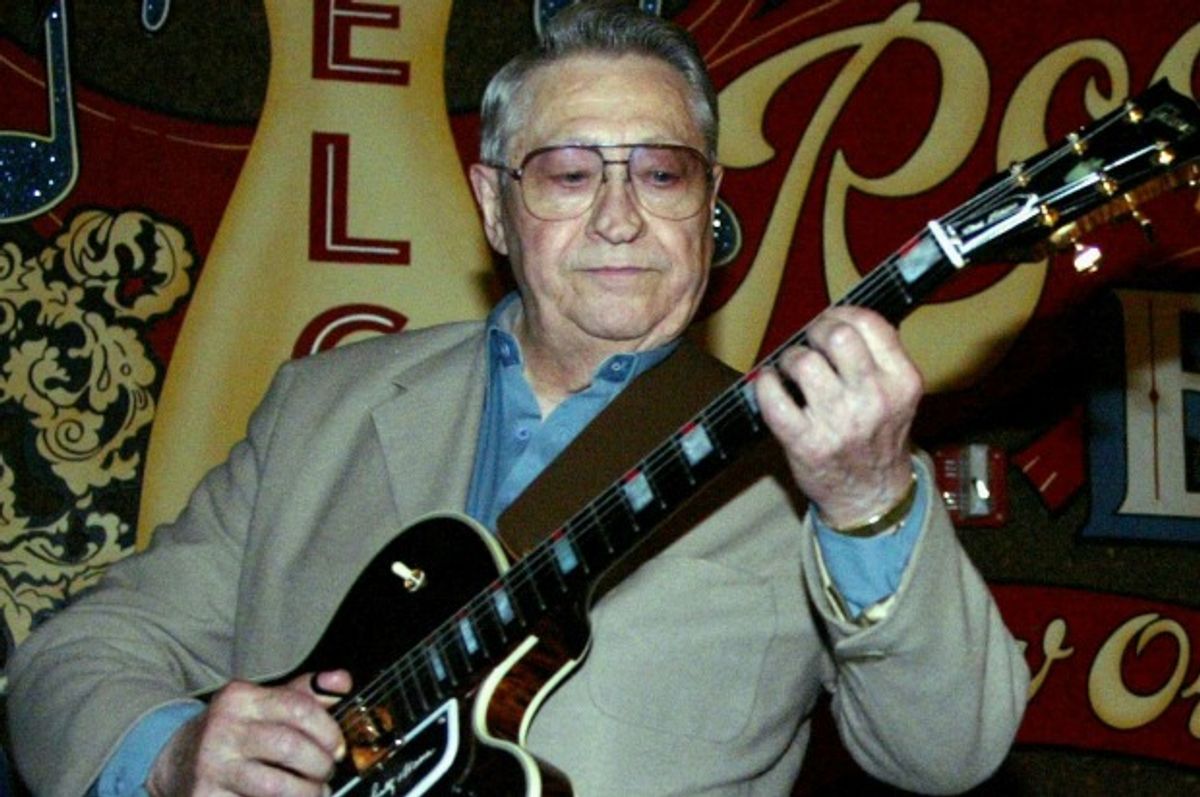

Elvis Presley’s career had its ups and downs, and the contrarian impulse among culture-lovers means that some fans and critics try to reclaim even his worst eras. But during Presley’s greatest periods — his first few years of recording, in the mid-1950s, and his 1968 Las Vegas comeback special – he was accompanied by guitarist Scotty Moore. Before and after, Moore kept a much lower profile, playing low-key sessions with other musicians, managing a recording studio, and recording solo sessions that very few people heard.

It was an appropriate course for a musician who, despite the excess and egomania of many rock guitarists, rarely played an extra note.

Moore’s death on Tuesday — at age 84, at his home in Nashville – means that the original crew that cut Presley’s Sun Sessions, arguably the most important recordings of early rock ‘n’ roll, is now all gone. Some of the genre originators – Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis – are still alive. But rockabilly, that combination of country and western with the blues that became the first rock style, has lost one of its last important pioneers.

Moore’s style came from a simplicity and rhythmic directness combined with a distinctive effect called slapback. He wasn’t the first to use it, but the tape-delay that came from his EchoSonic amplifier in songs like Presley’s “Mystery Train,” from 1955, not only shaped rockabilly, it became the signature sound of revivalists like The Cramps and Chris Isaac, a kind of shorthand of retro-‘50s style.

His admirers included Bruce Springsteen, Jimmy Page, and Keith Richards, who says he knew he wanted to become a rock guitarist after hearing Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel.”

“Everyone else wanted to be Elvis,” Richards said in Moore’s biography. “I wanted to be Scotty.”

Presley’s first recording was “That’s All Right (Mama)” an Arthur Crudup song that Moore recorded with Presley and bassist Bill Black. The three were messing around at Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios one so-far-fruitless night in July 1954 when Presley started nervously strumming a fast version of the Crudup song, with Black and Moore joining in.

As Moore told Guitar Player magazine in 2014: “Sam poked his head out of the door — this was before mixing consoles had a talkback button — and he said, ‘What are you guys doing? That sounds pretty good. Why don’t you keep doing it?’”

“So I got my guitar, ran through it a couple of times, and that was it. That was the beginning of, how do you say it, all hell breaking loose!”

The song, which rivals Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88” in its claim to be the first-ever rock ‘n’ roll recording, was backed with a version of “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” All of the Sun Sessions are indelible — “I Don’t Care if the Sun Don’t Shine,” “Baby, Let’s Play House” — and even a song that Sun never released, “Trying to Get to You,” is a masterpiece, with some perfectly-turned fingerpicking on guitar. Often, Moore’s lead plays against Presley’s rhythm guitar — what Moore called “filling in holes” with sharp blues riffs and country licks.

After a few years with Presley — their songs together included “Jailhouse Rock” and “Hound Dog” — Moore was making only a few thousand dollars a year while the singer became a millionaire. Col. Tom Parker began to block the access Presley’s musicians had to the new star. As Elvis became less of a musician and more of a product, the guitarist dropped out.

Because of his well-timed exit, Moore missed Presley’s drift into bad movies and irrelevance. But he returned at just the right moment – for the NBC special that saw Presley revisiting songs from the Sun years, some early hits, and the gospel songs that served as a musical taproot.

But Presley’s camp paid him very little for the gig – reputedly, not enough for him to cover his expenses — and never asked him to go along on the ensuing tours. Musicians knew Moore, but he never became household name the way some of his inheritors did.

As rock music got more decadent and musicians often disappeared into their own egos, Moore remained an old-school gentleman who carried his own guitar and amp to gigs. His style hardly evolved, and none of his other sessions, either leading a band or playing with other musicians, matched his success with Presley. He avoided the dizzying highs and plummeting lows that defined the careers of many rockers. Instead of leaving behind wild stories, he leaves us with a guitar sound that no one who’s really listened to will ever be able to forget.

Shares