America has become a resentful, bitter, and dissatisfied collection of cynics. Eleven percent of the population takes anti-depressant drugs, few people claim to have many close friends, and polling data regularly indicates that an overwhelming majority believe that country is “on the wrong track.” Pessimism and paranoia dominate everything right of center in the national dialogue, with Donald Trump routinely referring to the United States as a “hellhole” and “nightmare.” Hillary Clinton attempts to beat back the defeatist drumbeat with a song of hope and optimism, but lacks the melodic majesty of Barack Obama, who turned an anthem of hope into his greatest hit. Bruce Springsteen, a fine singer and songwriter himself, has an antidote for those afflicted with despair, and has a lifetime of music to act as remedy against social depression.

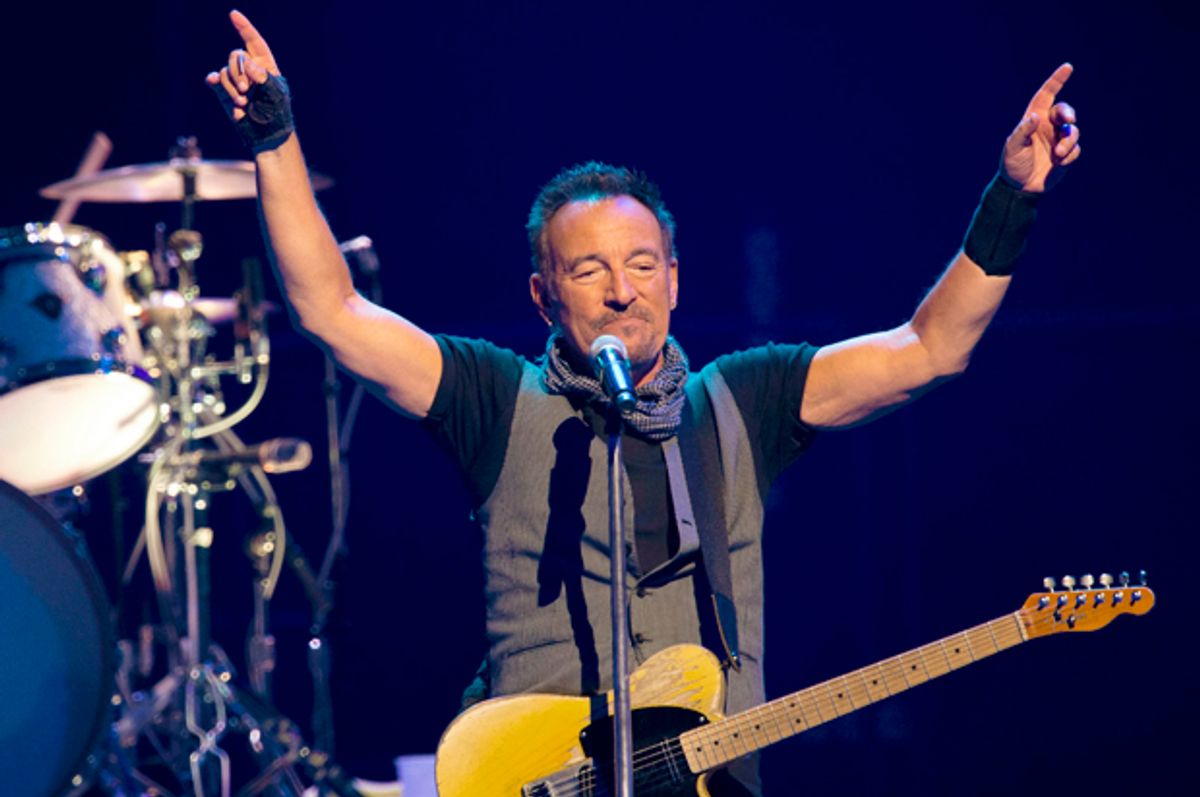

On Sunday, August 29, Springsteen and the E Street Band brought their rock 'n' roll revue to the United Center in Chicago, Illinois. Although the show was markedly less political than many Springsteen performances, it is hard to deny the subtle subversiveness of joy, hope, and pleasure in a nation troubled by low expectations and terminal diagnosis in the wake of every new development and headline.

At the age of 66, Springsteen offers an alternative to anyone unhappy about mortality. Playing for nearly four hours with more energy and intensity than most performers half his age, he makes one wish that laboratory scientists could bottle his genes and inject them into anyone searching for a second, third, fourth, or fifth act in life.

The E Street Band, with Jake Clemons, Clarence's nephew, now filling in for the deceased Big Man on saxophone and Charles Giordano substituting for the also deceased Dan Federici as organist, still plays with thrilling dynamics and enough hunger to make anyone forget that they have already been rattling the walls of arenas for nearly 50 years.

Over their five decades of rock 'n' roll mastery, Springsteen has earned his place alongside the more recent addition to the pop culture pantheon, Beyoncé, as one immune to all criticism. It is almost as if, by order of the state, any disapproval of “The Boss” is impermissible.

Given his godlike stature, I'll begin with sacrilege (I already paid penance in my first book, "Working On a Dream: The Progressive Political Vision of Bruce Springsteen"). Absent of any new, compelling material, Springsteen often relies too much on his charisma, which leads him to indulge in heavy-handed ham routines. Springsteen has never feared the corny, and in Chicago, there were many corny moments, especially during performances of cornier material — “Hungry Heart,” “I'm a Rocker,” and “Waiting On a Sunny Day” — the two latter songs of which were saved by his bringing children up to the stage to sing along with infectious gusto. Some of the more serious moments of the night — “Because The Night,” “The Rising,” “She's the One” — were so bombastic that they felt more like spectacle than song. Max Weinberg, E Street drummer, has taken to playing like he is auditioning for Slayer, and his "big, big beat," as Springsteen calls it, becomes a distraction, overpowering the guitar fills and vocal subtleties.

Lack of new material also hurt the show by not providing it with an anchor to hold down the classic songs. In tours past, Springsteen could orient his show, with a sense of purpose and mission, around new songs, showcasing the connection between fan favorites and fresh creations. Now, Springsteen has joined the ranks of his peers by performing mostly a “greatest hits” set on "The River" tour. The bombast and anthemic drama dulls after awhile, especially considering that, unlike The Rolling Stones, for example, it is difficult to find a song in his entire catalogue with any sexual groove and rhythm. The few flaws in a Springsteen show are destined for footnote status, however, as there is little doubt, as clichéd as it has become to say, that Bruce Springsteen and The E Street is one of the greatest live acts in the history of popular music. They don't show any signs of stopping, or even slowing down.

The most political, and one of the most dramatic, moments of the evening was when Springsteen and band played an aggressive, angry version of “American Skin (41 Shots).” Springsteen wrote the protest song in defiance against New York’s protection of the police officers who killed West African immigrant Amadou Diallo, firing 41 shots, after mistaking his wallet for a gun. Diallo removed his wallet after officers mistook him for a suspect in a criminal investigation. He was attempting to identify himself. Springsteen’s ferocious voice, showing no signs of wear and tear, thundered through lyrics that have taken on a sad new relevance in the era of the Black Lives Matter movement: “It ain’t no secret my friend / You can get killed just for living in your American skin.”

Jake Clemons, the only black member of the band, stood throughout most of the performance with his hands raised in the air. His own sax solo closed the song, stepping perfectly into the opening drum beat of “Murder Incorporated,” a power-chord, enraged rock song depicting the failure of American institutions to care for the inner cities. Drug dependency, gangland warfare, and the blight and obliteration of mass poverty devastate isolated pockets of America’s greatest cities. As Springsteen shouted his indictment of “Murder Incorporated,” before taking a fiery and frenetic guitar solo, the crowd was oddly quiet. Later, he would advance his rock ‘n’ roll demonstration for urban reconstruction with a call of support for the Chicago Greater Food Depository. The nonprofit had tables and donation forms in corridors throughout the arena.

In the middle of “American Skin,” when Clemons lifted his arms, an African American usher, turned toward the stage and applauded. It is the only time I have seen an arena employee actually cheer for the performer on stage.

The horror and hope in that moment when Springsteen pays tribute to an unnecessary life lost due to the unpunished crimes of those tasked to serve and protect, met with the unexpected applause of a young, black woman there, not to enjoy the show, but earn a small living, captures the essence of why Bruce Springsteen remains an American artist of great importance.

The applause seemed like the celebration of affirmation. Springsteen’s only political moment of the night was dark and indignant. Those qualities did not dominate the show. The most beautiful performance was the opening, “New York City Serenade,” complete with a local string section. The jazzy number from Springsteen’s 1972 record, "The Wild, The Innocent, and The E Street Shuffle" is a magnificent tribute to the magic of New York. It is a love song, but not a love song for any person in particular, or even the place of its inspiration. It is a love song for life. Like an invitation to a wondrous party, “New York City Serenade” gave forecast to the poetry and pleasure of the evening. Springsteen put it best in his own words from many years ago, “I cannot promise you life everlasting, but I can promise you life right now.”

“My Love Will Not Let You Down,” a "Born In The USA" outtake, demonstrated the enthusiasm of romantic courtship with rock ‘n’ roll fury. When Springsteen, sang up from his viscera in a guttural cry, “It takes two, baby!” in a tease of “It Takes Two” to close his own, “Two Hearts,” with Steven Van Zandt by his side, he expressed and exercised the power and importance of friendship.

“Mary’s Place,” a soulful classic from "The Rising," promised that good times are possible in the hell of heartbreak. The sadness of “Racing in the Street,” became secondary to the beautiful piano solo that ends the E Street jam; emphasizing the possibility of redemption in its final words: “Tonight my baby and me / We’re going to ride to the sea / And wash these sins off our hands.”

“Badlands,” just as it always does, raised rebellion to the prominence of a virtue. The energy of the band making it clear that to live with anything less than maximum passion is to violate the gift of vitality.

There were certainly times when the E Street Band could have played with more subtlety. “The River” was almost ruined by its overly dramatic delivery, for example. Also, the setlist would have benefited from fewer of the corny, poppy tunes, but in Springsteen’s finest moments, he achieves that to which few artists even aspire. He becomes affirmational. That is, he makes the idea of life more attractive. This is why every year or so someone writes an unbearable essay on how Springsteen is a religious figure, and his concert is a religious ritual. Those critics and analysts are dead wrong. Springsteen’s celebration of life is terrestrial and in the present. In American pop culture, Bruce Springsteen is the ultimate and most effective humanist.

So, when Springsteen is not political, he is profoundly cultural. More and more Americans believe their children will not have as good as lives as they did, and one can only hope they are not communicating their cynicism to their sons and daughters. Large amounts of Americans feel “disengaged” from their work, and it seems that the greatest deficit creating a crisis in the culture is a deficit of avidity.

That deficit is visible and palpable in the presidential race in which voters must decide between bigotry and stupidity and practical and incremental progress. The latter is likely the best that anyone, in all honesty, can ever hope to accomplish, but the limits of reality and the restraints of triumvirate government should not act as a ceiling on ambition. Art, especially in the hands of Springsteen, opens up a world of possibility – a “land of hope and dreams” – bigger and better than any legislation could ever create.

Springsteen makes it clear that he has no time for passivity or pessimism, and that the future has no room for those poisons. The future belongs, in the words of a rare song he played by request in Chicago, “to none but the brave.”

Shares