Last month, after reporting confirmed that Ryan Lochte had lied about being robbed at gunpoint during the Rio Olympics, the swimmer and reality television star sat down for an interview with NBC's Matt Lauer. When Lauer felt Lochte hadn't expressed sufficient remorse for his actions, he piped in. “Let me play devil's advocate for a second,” Lauer began.

The term "devil's advocate" has its origins in Catholic tradition and has historically referred to appointees of the Church who challenge a proposed canonization. A devil's advocate ensures that the Church isn't too quick to credit someone with the making of miracles; he prevents the naming of false saints. It's also an apt role for a journalist to play. Much has been made of the increasingly contentious relationship between the media and its political subjects, and that tension has led many to pronounce that the media's bias has prevented it from fulfilling its function. On the contrary, in order for media figures to live up to their obligations as members of the fourth (and fifth) estates, their relationships with their subjects ought to be tense, if not downright hostile.

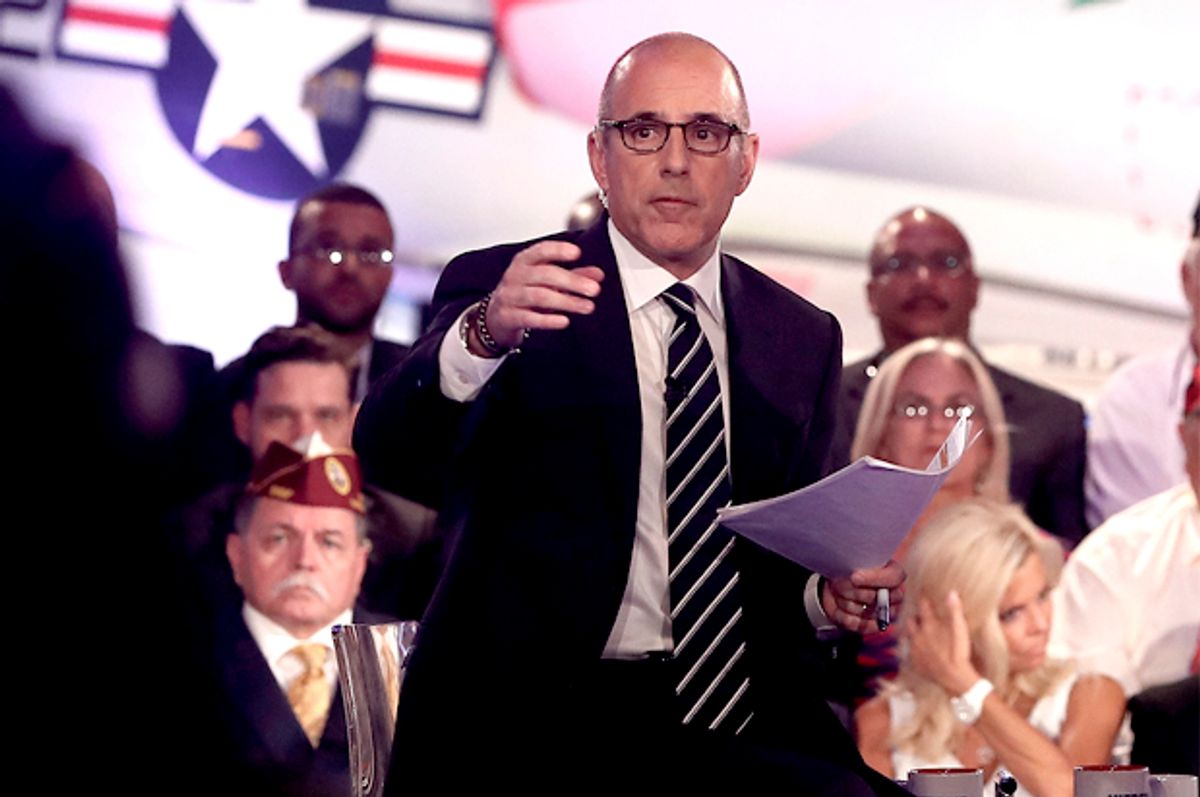

The take-away of Lauer's disastrous forum performance this week, during which he failed to challenge Donald Trump on either his profoundly stupid and uninformed ramblings or his boldfaced lies, has largely been that you don't send a celebrity journalist — one thought to be better-suited to interviewing members of One Direction than presidential candidates — to do a real journalist's job. Where the gold standards of the latter camp have brought about massive political transformation, the best a celebrity journalist can hope for is to make his interviewee cry. (A feat, it's worth noting, Lauer accomplished with one Ryan Lochte.)

Perhaps, however, the solution lies in holding our entertainment journalists to a higher standard than eliciting an emotional response from the celebrity he's covering. To be clear, I do not deny that celebrity culture has gotten wildly out of hand. In an ideal world, our obsession with the characters who populate our television screens (for they are, in every sense of the world, characters constructed by massive public relations teams) would cease, and we would take a far more measured approach to our fandom. In an ideal world, Lauer, now a celebrity in his own right, wouldn't be paid $28 million a year to interview his targets. But for now, a solid intermediate step might be to draw a sharper distinction, to reintroduce some of that healthy tension in the relationship, between the celebrity journalist and the celebrity.

It's a change that's long overdue, least of all because it produces good television. Watching Lochte get called out is infinitely more entertaining than watching sycophantic journalists kowtow to their subjects live on national television. But the marketplace only works when enough people reject the model. Why would any celebrity willfully subject herself to a tough, critical but fair interview when another outlet promises the fanboy-esque coverage to which she'd grown accustomed?

But more importantly, it's a change that would have an important and immediate cultural impact. Currently, celebrities have to willfully take on — either through ignorant words and actions or an explicitly activist stance — a political role in order to be viewed as political figures. Often, this has the unfortunate effect of demonizing those who protest or speak out about social justice causes, who are, equally unfortunately, often members of the affected groups. Their far more privileged peers often skate past thorny issues scot-free. The responsibility to take on oppression then falls to those most affected by it rather than those most equipped to end it. Journalists, “political” or no, ought to recognize that celebrities, by virtue of their access to resources, are all political actors.

Part of the reason why celebrity culture has gotten out of hand, and the reason why the famous enjoy a disproportionately privileged status, is this troubling lack of accountability. Celebrities have long-enjoyed the benefits of wealth and fame without any of the traditional checks on their power and without an actual fourth estate to keep them in line. Some members of fourth estate are perhaps too preoccupied with joining the ranks of the rich and famous themselves, and their charmed lives are part of a self-reinforcing cycle.

And, increasingly, it is not just the lines between celebrity and political journalism that have blurred but the lines between celebrity and politics. Trump was crowned with the Republican nomination on the strength of his celebrity alone, with those complicit in the creation of his brand now expressing profound regret over its unforeseen consequences. If politicians treat voters like viewers who can't tell the difference between celebrities and politicians, why should journalists treat them any differently?

Shares