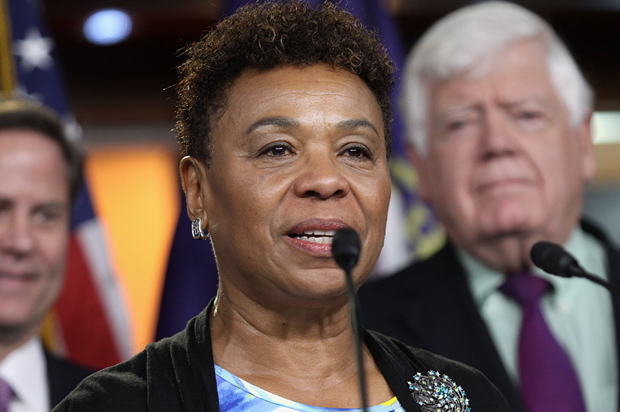

By one very important measure, Rep. Barbara Lee is the most progressive person in Congress: She was the sole person to vote against the 2001 Authorization of the Use of Military Force that gave President George W. Bush the authority to invade Afghanistan, which has been cited time and again to justify U.S. military interventions abroad in the years since. After the 9/11 attacks, a climate of intense jingoism pervaded American politics. While many elected officials on the left might have shared Lee’s misgivings, she was the only one with the courage to join a small number of protesters and say no to war.

Fifteen years later, the horrible state of affairs has proved Lee right. The “War on Terror” continues, including the U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. Instead of defeating terrorism, war has fomented the rise of new enemies like ISIS and plunged large regions of the world into bloody chaos.

Lee’s courageous vote has earned her a lot of respect on the left and so some were surprised when she declined to endorse Sen. Bernie Sanders, or anyone at all, during the Democratic presidential primary. Lee discussed that decision and other matters with Salon. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You are quite literally one of a kind. After the September 11th attacks, you were the only person in Congress, out of 535 people, to vote against the Authorization for Use of Military Force that gave Bush the green light to go into Afghanistan. And that today has been cited to authorize unrelated military operations around the world. At the time, you received an often ferocious, though in some cases friendly, response from the public and the media. Tell me a little bit about what that was like.

First of all, for me personally, I felt the brunt of the anger and the frustration that people felt. I was very sad and upset and angry like everyone else because we lost so many lives in that horrific attack and so many people were injured — and now we see lifelong diseases and injuries. My chief of staff’s cousin was Wanda Green, she was on Flight 93. And so just on an emotional and personal level, it was a very difficult time just like [for] every other person who felt the pain and anguish and anger of the moment.

And then what was that like, the response that you got for voting against the Authorization for Use of Military Force?

I received all types of death threats, harassment. I was called a traitor, committing acts of treason. People were very angry. My opponent then walked in the parade with Rudy Giuliani in New York, and she carried a sign “Barbara Lee hates America.” And her website had the World Trade Center towers burning with my picture smiling in front. It was really awful.

But on the other hand, many people understood that that was a blank check setting this country up to wage war in perpetuity. My vote against that resolution had nothing to do with my not believing we needed to bring the perpetrators to justice. So I’m clear on that. My dad was a military officer. This had nothing to do with the fact that I knew we had to do something.

But three days after the attack, coming up with a broad blank-check authorization that allowed the use of force really in perpetuity, to me, was wrong. It was giving away the authority, then to President Bush, now President Obama, and any future president, until we repeal it. And even though it was a difficult vote, I still believe that was the right vote.

I have to say that my colleagues and others were very comforting and very respectful of my vote. Even Chairman Hyde, Republican chairman for the foreign affairs committee I served under, he hugged me. In a lot of ways those comments, and those gestures, and my faith in God and my family and close friends, really sustained all the angry and bitter reaction toward me, which was very dangerous. It was very dangerous.

Given the last 15 years of seemingly endless, ineffectual, immensely destructive wars, it seems — I’m sure you’re not celebrating this — but it seems to have proven your concerns to have been the correct ones. Have some of your colleagues come around since then to acknowledge that you were right to vote against the legislation?

Well, they may not have said I was right. Some have told me that privately and some publicly on the floor. But I think what’s important is to look at the votes to repeal that authorization — and we’re up to maybe 140-some votes. And I have been offering an amendment, freestanding resolution, in a variety of vehicles on the floor to begin to build support to repeal it.

And so we have 140-some members who now believe in what I said. It was a blank check. We need a new debate and a new authorization to continue with these wars that are taking place. Whether they agree or disagree with a new authorization, minimally many members, Republicans and Democrats, are saying we need to have a debate.

It does seem like a lot of the people who would like to repeal the authorization would just like a new one rather than make a stronger anti-war statement in general.

That doesn’t make any sense, though, because as long as you have that one on the book, it can be used anywhere. It says the president is authorized to use force against any nation, organization, individual connected to or responsible for 9/11. It was very broad. It’s been used over 37 times, which the Library of Congress verified. And those were the declassified times it has been used. And so that needs to be repealed.

Why come up with a new one when you can still use that one? That was one of the problems I had with the president — and to his credit, he put one forth, which the speaker, Boehner now Ryan, have not taken up. But in his resolution, he did not repeal the 2001 [authorization]. And so I [could] not support that because until we repeal that one, we’re still in a state of perpetual war. And we’ll continue using that to use force or for whatever reasons: wiretap, Guantanamo.

The push and pull between the White House and Congress seems more about who is going to take responsibility for military actions, instead of the really deeper discussion, reflection, debate over whether all of these military actions are a good idea.

Well that’s what a debate would bring forth. We just haven’t done our jobs. We’ve been ducking and dodging. That’s what’s happened. It is our constitutional responsibility to do it. Not the president. We have the responsibility to authorize the use of force.

And now that constitutional question is making its way into court with this soldier’s lawsuit, correct?

Yes, that’s right. We’ll see what happens. Many interpret the Constitution as being clear on Congress’ level of responsibility.

It does seem pretty straight forward, the constitutional wording. Has the question of repealing come up in the presidential race?

I haven’t heard it come up. If it had come up, it would have been in the primary. But Sen. Sanders voted for it, so did Sen. Clinton. They both voted for it so it didn’t come up during the primary, from what I remember. I know the Iraq resolution has come up.

This is one thing that I do have a lot of trouble wrapping my brain around: It’s not that most Democrats voted for the bill — after all, lots of Democrats vote for a lot of bad things — but what really troubles me to this day, is that not a single one joined you in voting against it. And we’re talking about some otherwise very progressive elected officials, Dennis Kucinich, Cynthia McKinney, Bernie Sanders. Why?

You have to remember the moment, though. It did surprise me. But within the context of what had just happened, members of Congress are human beings also. They have emotions and at that point everyone wanted to be unified and thought that unity was the overriding principle that should drive whatever votes would be cast.

That vote not only cast a long shadow in terms of the military adventures that it’s led to, but also politically, in the sense that Hillary Clinton and other Democrats and Republicans now take a lot of heat for their vote for the Iraq War, but the anti-war critique is really limited in a lot of ways to Iraq.

I think by 2004, maybe before, you started to see this sort of liberal consensus emerging that the Iraq War was the bad war and that Afghanistan was the good one. In 2004, you had John Kerry criticizing Bush for taking his eye off the ball in Afghanistan by invading Iraq. There is still very little public discussion of the idea that the Afghanistan war has turned out to be an enormous disaster as well.

But you know what, repealing this and having a debate and a new authorization could bring all those issues out. People have accepted the state of war against Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria as the norm. And that’s a very tragic and dangerous place to be. This is the new norm, being in a perpetual state of war. And until the public demands that Congress and their members do their job, it’s going to be like that, unfortunately.

During this year’s Democratic primary, you didn’t make an endorsement. How did you go about making that decision? It seems like on policy you were more aligned with Sen. Sanders than with Secretary Clinton. Why did you decide to stay out of it?

Well, I wanted to be a member of the drafting committee of the platform. In order to be sure that we had a progressive platform, I had to have some legitimacy and credibility with both sides. And so I think I really accomplished that, along with others. Many of the policy provisions of that platform were presented by Sen. Sanders — [which,] of course, I supported — and I helped negotiate some of those provisions.

And after we completed the platform, I did endorse Secretary Clinton. But I really wanted to make sure I had that space to be part of the process [to] craft a progressive platform.

Your membership on the platform drafting committee — that had been under discussion for a while back with Chairwoman Wasserman Schultz?

I asked to be on it. I made a request to be on it. I was on it before in 2012, the drafting committee of the platform. That was my intention, not knowing for sure if I would be appointed, but I made the request and I was appointed.

What’s your take on the final platform? It was celebrated as the most progressive in party history but also criticized for falling short on the [Trans-Pacific Partnership], fracking and the occupation of Palestinian territories. What would you say to progressives that —

Well, we didn’t get 100 percent. Clinton and Sanders — neither side got 100 percent. Given the dynamics of the platform committee, and the nominee having more members on it, I think the platform came out very progressive. I don’t think Clinton got 100 percent, nor did Sanders.

I think it was a platform that everyone could embrace and recognize that people did their best to make it inclusive, progressive. I made sure we had people with different points of views on as witnesses, different constituencies came to testify, voices that have never been heard before. I submitted names of people that never would have been there had it not been for the negotiations.

Looking back at the Sanders campaign and its surprising success, and looking forward, what’s your assessment of the strength of progressives and the left within the Democratic Party?

Just from a member of the Progressive Caucus, as the chair of the Global Peace and Security Task Force, and one who’s been with the Progressive Caucus since I’ve been in Congress, I see how the majority of Democrats really have embraced the policy agenda of the Progressive Caucus: $15-an-hour minimum wage, living wage, no privatizing of Social Security.

When you look at the policy agenda of the Progressive Caucus and when you look at the majority of the American people and where the polls are saying that people are, I think it’s [a] mainstream agenda that speaks to the values of not only our Democratic Party, but to every American. I am very proud of the work and we’re the largest caucus in Congress. And we’re very diverse.

What would you say to Sanders supporters, especially young people who are getting involved with politics for their first time, and this is their first big, political defeat that they’ve experienced and are upset? What would you say to them about the work ahead?

I would say that it was not a defeat. When you look at the platform and the influence that young people made, and the Sanders voters, 13 million plus voters, it was a major victory. I think Sen. Sanders has said that. Myself, in the early ’70s, I wasn’t even registered to vote, and Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm — who became my mentor and I worked on her campaign, I organized her Northern California primary. She convinced me, and she was right, that if you really want to change the country and make things better for people, then you’ve got to get involved in politics.

You’ve to register, you’ve got to vote for those candidates. And knowing and recognizing nothing’s perfect and you’re not going to get 100 percent. So that doesn’t mean you don’t get involved and push the envelope and stand for what you believe in and be a voice for people who have been marginalized. And be a voice for your points of views and where you think the country should go. So I think it was a big win, and I’m very proud of what Sen. Sanders and his voters did: They influenced the Democratic Party.