It’s impossible to summarize Shep Gordon’s life and career in just a few sentences. Born in Jackson Heights, Queens, he first rose to fame as the promotion-minded manager for ’70s rockers Alice Cooper. From there, Gordon launched a successful career managing artists such as George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic, Blondie, Anne Murray, King Sunny Adé, Teddy Pendergrass and Luther Vandross.

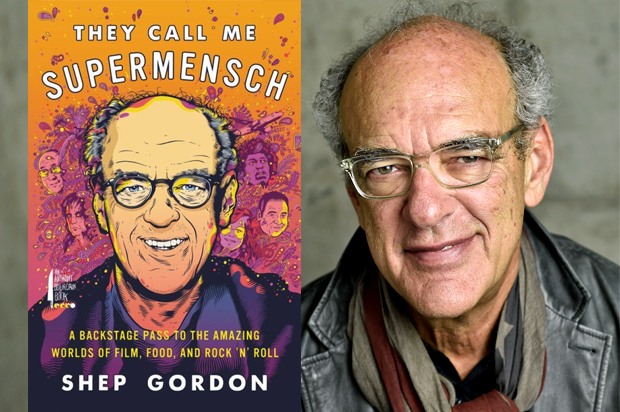

The mogul’s riveting new autobiography, “They Call Me Supermensch,” certainly touches on these musical adventures. However, the book also exposes the breadth and depth of Gordon’s life and work — producing movies, working with icons such as Groucho Marx and Raquel Welch, and helping legitimize celebrity chefs such as Emeril Lagasse and Wolfgang Puck — and offers stranger-than-fiction stories, such as meeting eccentric genius painter Salvador Dalí or being pals with the Dalai Lama.

Although Gordon is notorious for dreaming up outlandish stunts, such as tossing a live chicken onstage during an Alice Cooper concert, he always operates with compassion. In fact, throughout “They Call Me Supermensch,” Gordon espouses his “coupon” philosophy: If someone does him a solid, he offers that person a figurative “coupon” — a benevolent I.O.U., in a sense — that can be redeemed any time for a favor. Brilliant, gratitude-filled insights such as these ensure “They Call Me Supermensch” is a worthy companion to actor Mike Myers’ 2013 Gordon documentary, “Supermensch: The Legend of Shep Gordon.”

Today, Gordon is mostly retired, although he still manages Cooper — in fact, the old friends are doing a talk in L.A. in February dubbed “Alice and Shep: A 47-Year Conversation” — and oversees a New Year’s Eve charity event to benefit the Maui Food Bank. In mid-December, Gordon checked in with Salon via phone from Hawaii, where he’s lived since the ’70s, to talk about how gratitude factors into his life and what he learned about his father from writing “They Call Me Supermensch.”

In the intro, you wrote that you said yes to writing this book to help you understand why your life has unfurled the way it has. After you finished writing it, did you feel you achieved that goal?

I wouldn’t say fully, but I had some amazing revelations. Personal revelations that were significant to me, particularly about my relationship with my father. I’d grown up really loving my father, but always thinking of him as fairly weak. And what I realized through writing the book was he probably was the strongest man I ever knew. He sacrificed everything for me, my brother and our family. So that was a real revelation, that sometimes you can mistake service for weakness. When I looked at my own life, and looked back at it, I realized that the choices I made were sort of choices he would have made. I just made them louder, on a more public stage.

What other unexpected insights did you glean after you sat down and wrote the book?

I started to see a rhythm in how I approached my business, both on a. . . I don’t know if you’d say moral level, but a human level, and on a professional level. Professionally, I realized that what I was doing was really attaching the faces of the people I worked with to what I called “waves” in society. What I mean by a wave is. . . right now, cannabis is probably a wave. There’s this huge movement of dollars and curiosity and people towards it. But there’s no face of the movement.

That same thing existed in the culinary world. [During] the time I started representing chefs, you couldn’t get into Spago. You couldn’t get into Le Cirque. You could get into Broadway Place, if you had money. You could get into, you know, Super Bowls if you had money. You couldn’t get into these restaurants. So the demand was there, but there was no face of the demand.

For Alice [Cooper], it was more of an overall sociological pattern. Every child rebels against their parents when they’re growing up. We see that through the culture. We see that through the clothes they wear, the way they groom themselves, the music they listen to. Growing up, long hair was what really irritated my parents, so we all had long hair. With my kids, when they wore their pants so I could see their underwear, I hated it. So they all did it. [With] Alice, we tapped into that. It was “Let’s go after getting parents not to like us, and kids will love us.”

With Teddy Pendergrass, it was sort of the sexual revolution that was going on, where you could finally start to really talk about sex. When I realized there was going to be video, when movies went to video discs, and cassettes, I did the first video album with Blondie, called “Eat to the Beat,” where we did the whole album on video not because we could sell a lot, but because I wanted [frontwoman Debbie Harry] to be the face of that technology. With all of [these clients], I attached them to these waves — culturally, societally and technologically. So that’s one thing I learned.

And then the other thing that I saw was that I always made choices to be compassionate. I did it for reasons that in the beginning were selfish. And as I grew and got mentors, I realized that not only was it selfish, it was the best thing I could do. What I mean by that is, I represented talent, so I wasn’t living my life, I was living other people’s lives. They only had one life. I, as a manager, could move from act to act. But when you represent an artist, they only have one life. If you fail them, you can go to your next artist. They have to live with that failure.

That’s sort of a tough responsibility. So the thing I always told them, selfishly, is that when you look into the future, nobody ever just goes up. Nothing ever just goes up. Newton’s Law applies to everything, including careers. The entertainment business is a small world. So you’re going to meet the same people coming down [that] you met going up. If you’re compassionate with them, and you’re fair with them, and you try and do win-win situations, it’ll come back to you tenfold.

[I have] so many examples where it came back to really pay off. There was a time in the history of the music business where acts paid to be an opening act for a big attraction. So a record company would come to someone like Alice, and offer us money to put an act on the show so they could have exposure. We took an act, we got $500 a night for the act to put them on the show. I went to Alice, and I said, “Listen, if we take the $500, this band is going to not have hotel rooms, they’re going to all be driving in a van, tired. Is this really the way we want to treat the humans that are opening our show?”

For us, to give them the $500 meant nothing. I mean, it meant something, but it didn’t mean much. And for them, it meant a lot. And I said, “Who knows — someday, we may be opening for them.” The act was Mötley Crüe. And we just did 100 shows with them.

Those are the things I saw in my life. I’ve had lots of little tricks, little branding tricks, that I think for people who are interested in the kind of work I did, that can help them in that. But I think the big life lesson is: Be compassionate, be of service, and it’ll make you happier and more successful.

As you were sitting down and writing the book, what was the biggest challenge for you?

One of the biggest challenges was really remembering if what I thought was true, was true. I lived in a pretty fast lane, used a lot of things to change my realities. And had incidents. . . like in the [Mike Myers] movie, where [I talked about seeing] Pablo Picasso sitting with Mr. [Chef Roger] Vergé. Because we fact-checked the movie, we knew that it couldn’t have happened. But in my brain, it’s still there. So that was probably my biggest challenge. Almost every story, I went back to talk to whoever was involved to see, Did I remember this properly? Or is this some manifestation of my ego?

Wow. That is laborious fact checking.

Actually, it was fun, because I reconnected with so many people that I hadn’t talked to in years. It was a great part of the journey. . . . All the stories, there were some I left out because I couldn’t fact-check. But it was a fun project.

I was going to ask how you decided what to put in and what to leave out, because you do have so many stories throughout your life and career.

It was just really free flow. Now that I’ve read the book, I realize there’s so many other stories, and people remind me of stuff. But for me, it sort of accomplished the purpose I was looking for, which [is] it really gave me some sense of why I did what I did. I know I’ll never know the big answer of “What’s it all about?” but it was like a big sigh of relief. Because I always thought that I lived in reaction to my mother. That I lived under this dark cloud of proving to her something. Through the book, I realized, no, it was really the love of my father that drove me.

The key, by the way, for me was reading Norman Lear’s book [“Even This I Get to Experience”], which I thought was the best autobiography I’ve maybe ever read. But he talked about his relationship with his father. And even though his relationship with his father was completely the opposite of mine — his dad went to jail at a young age, he had a tough relationship — it opened my mind to the first time.

In the Jewish world, we always think about our mothers. It’s just part of the fabric. I never really thought about my relationship with my dad. And when I started to go and research who he actually was — because I only knew him as my dad — I found this entirely different person. Just completely different. A party animal, sort of.

I never saw him, ever, do anything, except watch TV and go to sleep, have dinner. I didn’t think he had any friends. I found that he worked at a brewery, and he had a house with five other guys on Staten Island that had a beer keg and parties every night. He was a handball champion, and an assistant golf pro. I mean, all stuff I had no idea, that he actually had a life. He never drove a car. I never bothered to ask him why, [because it] fit into my picture of this timid, weak, sort of scared guy, who was beautiful. And what I realized was that he really just gave it all up for us.

That’s pretty mind-blowing to discover something like that, after thinking something else for so many decades.

It was like a ton of weight off my shoulders. So I guess the short line is that writing the book was like 70 years of psychotherapy. [Laughs.] But I never really went for any counseling, ever in my life.

Did agreeing to let Mike Myers do the documentary on you make it easier for you then to say yes to doing the book?

Yeah, much easier. I had real problems in the beginning, particularly the name “Supermensch.” It was hard for me to look someone in the eyes and say that. [After] the reaction that people had to the movie, and to this person who the movie represented me as, I became much more comfortable with it. I don’t really consider that person in the movie, necessarily, [to be] me. It is certainly built from me, and aspects of me. But in the book, you get a much more human picture. That sort of made me into a superhero, and that was pretty weird.

As a guy who has self-worth issues, to have people tell you how great you are, and how you changed their lives, and “Oh my God, I wish I was you,” it’s sometimes very hard to accept. But I’ve found a way to do it and become comfortable with it. I have the same self-worth issues that every other human has. You look in the mirror, and basically you see a jerk. And then you figure out how to not be a jerk for that day.