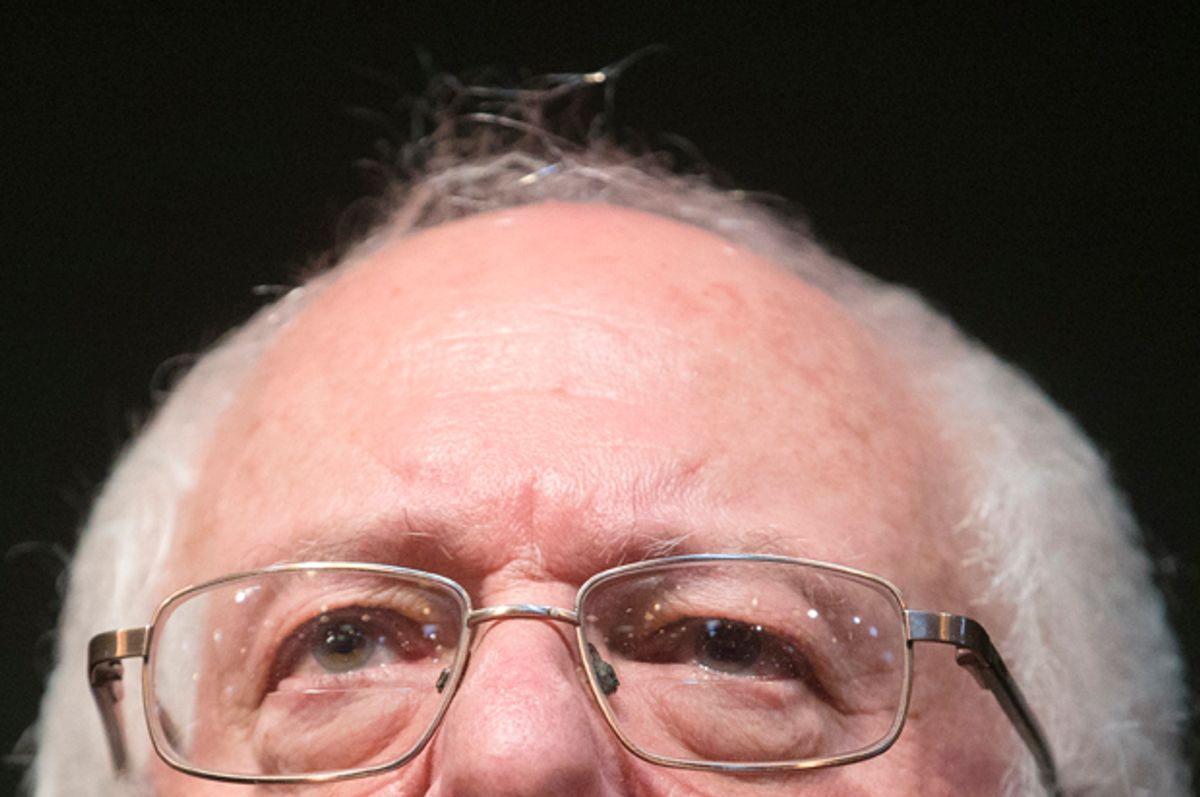

During a CNN town hall held by Sen. Bernie Sanders last Monday, the Vermont senator and progressive icon tried to drive home a point that he has frequently made in the past: There is widespread support for most of the economic policies that he ran on, even if they were often portrayed as radical and divisive by the media.

“The overwhelming majority of the American people — including many people who voted for Mr. Trump — support the ideas that we’re talking about,” insisted Sanders. “On many economic issues you would be surprised at how many Americans hold the same views. Very few people believe what the Republican leadership believes now: tax breaks for billionaires and cutting Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid.”

Public polling tends to support his claim. A Gallup survey from last May, for example, revealed that a majority of Americans (58 percent) support the idea of replacing the Affordable Care Act with a federally funded health care system (including four in 10 Republicans!), while only 22 percent of Americans say they want Obamacare repealed and don’t want to replace it with a single-payer system. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll from last year had similar results: Almost two-thirds of Americans (64 percent) had a positive reaction to “Medicare-for-all,” while only a small minority (13 percent) supported repealing the ACA and replacing it with a Republican alternative. These are surprising numbers when you consider how the Sanders campaign’s “Medicare-for-all” plan was written off by critics as being too extreme.

On other issues, a similar story presents itself. Public Policy Polling (PPP) has found that the vast majority (88 percent) of voters in Florida, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin -- four crucial swing states, three of which went to Trump this fall -- oppose cutting Social Security benefits, while a majority (68 percent) oppose privatizing Social Security. Similarly, 67 percent of Americans support requiring high-income earners to pay the payroll tax for all of their income (the cap is currently $118,500), according to a Gallup poll. America’s two other major social programs, Medicare and Medicaid, are also widely supported by Americans, and the vast majority oppose any spending cuts to either. In fact, more Americans support cutting the national defense budget than Medicare or Medicaid.

It goes on and on. A majority of Americans, 61 percent, believe that upper-income earners pay too little in taxes. A majority of 64 percent believe that corporations don’t pay their fair share in taxes. Significant majorities believe that wealth distribution is unfair in America, support raising the minimum wage (though perhaps not as high as Sanders would like), and say they are worried about climate change.

So a consistent majority of Americans would seem to agree almost across the board with a self-proclaimed democratic socialist and object to the reactionary agenda of congressional Republicans. How, then, did we end up with a Republican-controlled Congress that is dead set on repealing the ACA without a viable replacement (let alone a single-payer type of system supported by the majority); cutting and possibly privatizing Medicare, Social Security and Medicaid; slashing taxes for the wealthiest Americans; and ignoring climate change?

One answer that usually comes to mind is the culture war. The modern political era can be traced back to the 1960s, when various liberation movements — from Civil Rights and gay liberation to second-wave feminism and the anti-war movement — emerged to combat different injustices, including white supremacy, gender inequality, homophobia and American imperialism. These progressive movements rapidly changed America’s cultural and political landscape, and triggered a reactionary movement that author Thomas Frank called “the great backlash” in his 2004 book “What’s the Matter with Kansas?”.

The Republican Party exploited reactionary sentiments that had surged in response to the tumultuous '60s, and a great backlash ensued. The GOP appealed to racist and resentful whites in the South, who felt persecuted by the civil-rights legislation that had finally brought legal equality to African-Americans. (This is a good example of the popular maxim: “When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression.”) The so-called Southern strategy was set in motion by Richard Nixon and perfected some years later by Ronald Reagan, and this precipitated a complete political realignment that saw the South go from being solidly Democratic to solidly Republican.

Since this realignment, the culture wars have steadily taken over American politics, and the reactionaries have invariably lost ground as social and moral values have evolved and Americans have become increasingly tolerant. Consider LGBT relations: In 2000, only 40 percent of Americans found gay or lesbian relations morally acceptable, according to Gallup; by 2015 that number had increased to 63 percent.

Ironically, this has actually benefited many right-wing culture warriors, who have taken up increasingly frivolous issues over the years for political gain (like the "War on Christmas,” for instance). As Thomas Frank observed in his aforementioned book: “As culture war, the backlash was born to lose. Its goal is not to win cultural battles but to take offense, conspicuously, vocally, even flamboyantly. Indignation is the great aesthetic principle of backlash culture.”

For the economic and political elite, of course, trivializing the culture wars and inventing fictitious issues like the “War on Christmas” has always been the aim, because it divides the public and diverts attention from other issues — especially fundamental questions of economic and foreign policy. It is no coincidence, then, that economic policy has been drawn inexorably to the right over the past several decades as the populace has become increasingly divided over cultural disputes, even though the majority of Americans support progressive economic policies.

This is only part of the story, of course. While a culturally divided populace has no doubt benefited America’s power elite, the rightward economic shift was primarily a result of corporate America and other monied interests successfully infiltrating Washington with an army of lobbyists and flooding the political system with big money (an interesting backstory to this is told in the book “Winner-Take-All Politics”).

A 2014 Princeton University study conducted by professors Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page confirmed this phenomenon, and illustrated that modern America is more of an oligarchy than a democracy. “When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites or with organized interests, they generally lose,” write the researchers. This largely explains why a majority of Americans can support the economic policies advocated by Sanders, yet mainstream critics can decry his platform as “pie-in-the-sky” idealism.

The goal of Sanders’ presidential campaign was not only to take on the economic elite in America, but to promote solidarity among divided working-class and middle-class Americans and, eventually, to smash the plutocracy. This led many critics to accuse him of disregarding important cultural and social issues in favor of economic ones.

“If we broke up the big banks tomorrow,” asked Hillary Clinton during the primaries, “would that end racism? Would that end sexism? Would that end discrimination against the LGBT community?” It was a specious argument, of course, and one would be hard pressed to find any reasonable person who has suggested that economic reforms would suddenly cure all social ills or eliminate something as entrenched as racism. But economic and social issues tend to be interconnected. Racism against African-Americans, for example, was largely a product of landowning elites in the colonial era seeking to divide poor whites and black slaves after Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. As Michelle Alexander documented in her influential book, “The New Jim Crow”:

Deliberately and strategically, the planter class extended special privileges to poor whites in an effort to drive a wedge between them and black slaves … These measures effectively eliminated the risk of future alliances between black slaves and poor whites. Poor whites suddenly had a direct, personal stake in the existence of a race-based system of slavery. Their own plight had not improved by much, but at least they were not slaves. Once the planter elite split the labor force, poor whites responded to the logic of their situation and sought ways to expand their racially privileged position.

The point Sanders has attempted to make over the past two years, it seems, is that class can help transcend other social and cultural divisions and promote an economic solidarity that would go a long way toward overcoming deeply entrenched parochial beliefs and attitudes.

Of course, after the election of Trump — a politician who epitomizes “backlash culture” — the idea of overcoming things like racism and sexism in the near future seems far-fetched. But a different kind of backlash will ensue, perhaps, once the Trump administration and the Republican-controlled Congress start enacting their widely unpopular economic agenda.

Shares