On March 31, Rhino Records released a deluxe edition of Fleetwood Mac's "Tango in the Night." First released in 1987, the LP embodies the era's glossy combinations of flashy rock 'n' roll and airy synth-pop. Layers of gauzy harmonies envelop Christine McVie compositions "Little Lies" and "Everywhere;" glittering keyboards add melancholy to the Stevie Nicks-helmed "Seven Wonders;" and jagged, lightning-bolt guitar riffs cut through "Isn't It Midnight" and the title track.

Despite its effortless sound, the record took 18 months to make. Nicks was absent for most of the proceedings, owing to a packed tour schedule for her 1985 solo record "Rock a Little" and then a trip to Betty Ford to get sober from cocaine (the "Tango in the Night" song "Welcome to the Room. . . Sara," in fact, is about this rehab visit). Prior to the launch of Fleetwood Mac's tour in support of the record, Buckingham left the band. The core group of Lindsey Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, Christine McVie, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood wouldn't reunite and play together until 1997.

Despite the rocky genesis, "Tango in the Night" became one of the band's biggest-selling studio records: The record is certified triple platinum, trailing only '70s juggernaut "Rumours" in terms of sales, and spawned multiple Top 20 Billboard singles, including the Top 5 hits "Big Love" and "Little Lies."

For a certain segment of Fleetwood Mac fans, this album is as important as "Rumours." In fact, the LP is a sonic touchstone for modern production, particularly in the way pop-leaning acts seamlessly combine electro and rock influences. HAIM's soft-glow synth-rock, Best Coast's lush production and the plush approach of countless electropop acts all nod to "Tango in the Night." On the cover tip, synthesizer-heavy act Hot Chip has performed "Everywhere" live, while Hilary Duff did an EDM-influenced studio version of of "Little Lies."

Yet "Tango in the Night" also resonates with guitar-centric acts: Leadoff track "Big Love" has become a popular YouTube cover, and both indie-pop act Vampire Weekend and singer-songwriter William Fitzsimmons have covered "Everywhere." "Tango in the Night" felt like the dawn of a new, more expansive-sounding Fleetwood Mac.

For two of the people intimately involved with "Tango in the Night" — co-producer Richard Dashut and engineer Greg Droman — the record's success and enduring popularity wasn't exactly expected. By all accounts, making the album was a grueling, tedious and intense process, both physically and emotionally. Technology was both an aid and a hindrance, and the ever-simmering tension within the band was always threatening to surface once again.

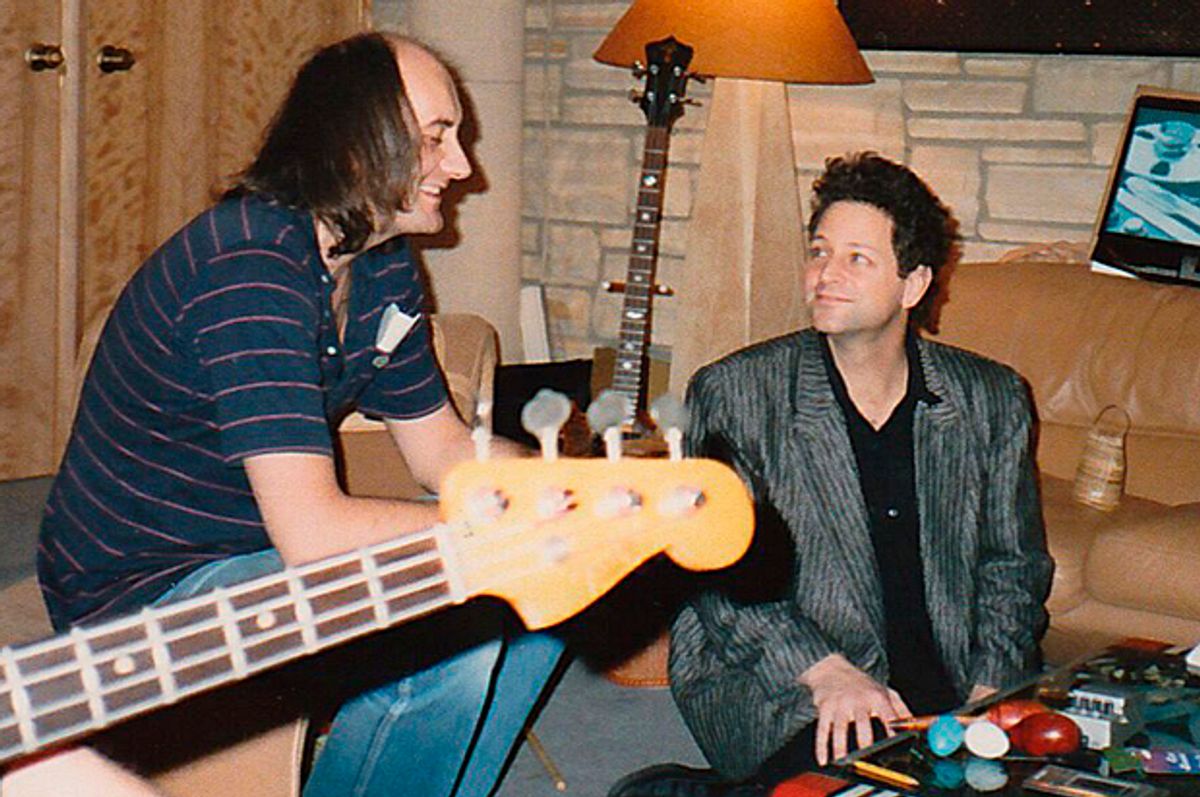

Dashut and Droman spoke to Salon about working on "Tango in the Night," and how the record came together.

How "Tango in the Night" started

By the time of "Tango in the Night," Dashut had been working with the members of Fleetwood Mac for well over a decade. (In fact, Nicks was his one-time roommate; as he recalls, among other things, she cooked Hamburger Helper and did the laundry.) He was an assistant engineer on 1973's cult classic "Buckingham Nicks" LP, and co-produced the Fleetwood Mac LPs "Rumours," "Tusk" and "Mirage" along with the band and Ken Caillat. "Tango in the Night" marked his first co-production credit without the latter.

"I'm almost most proud of ['Tango in the Night']," Dashut says during a Skype video interview. "By that time, Ken wasn't with us. I had more of a direct input with Lindsey. And Greg was just such an amazing help."

Perhaps unbeknownst to Dashut and the band, however, Droman reveals that he was "pretty new and young and inexperienced" at the time.

"I didn't know what the hell I was really doing," the engineer says, speaking by phone in a separate interview. "I really didn't. I learned pretty quickly that just the personal vibe of them feeling comfortable made as much difference as what you knew. I'm sure they could've sought out the best guy in the business at the time. They just didn't — they went with me," he laughs.

Droman was also relatively new to Los Angeles, having been convinced to move to California from Ohio by Eagles guitarist Joe Walsh, with whom he had toured. The transplant ended up working on staff at Rumbo Recorders, a studio "owned by the Captain & Tennille, of all things," Droman says. "And it was sort of known as a hair band studio. I met Ronnie James Dio and Ratt. Guns n' Roses did their first album there. REO Speedwagon lived there, pretty much."

Droman first crossed paths with Richard Dashut at Rumbo. The latter was producing a Christine McVie cover of the Elvis Presley-popularized "Can't Help Falling in Love" — which also featured instrumental contributions from Buckingham, Mick Fleetwood and John McVie — for the soundtrack to a movie called "A Fine Mess." Dashut and Droman "just hit it off," Droman says. "We had a really good chemistry, we just had a lot of fun together."

Several weeks later, Rumbo's studio manager informed Droman that Buckingham wanted to return to the studio, as he was cutting the song "Time Bomb Town" for the "Back to the Future" soundtrack. "I said, 'Oh, great! I'll help out on the session, whatever I need to do,'" Droman recalls. "And the studio manager said, 'No, they want you to engineer it.'"

Buckingham then tapped the engineer once again as he started work on a solo record at Rumbo. At the same time, Fleetwood Mac was rumbling back to life and started working on what would become "Tango in the Night." To facilitate both projects, Buckingham's bandmates moved into a studio down the hall.

"Now that I know how things work with them, it was a ridiculous idea," Droman says with a hearty laugh. "There was no way that was ever going to work." Still, the two camps worked in parallel for a spell. A different engineer collaborated with Fleetwood Mac, while Droman continued engineering Buckingham's solo record.

Sessions for the latter were put on hold as "Tango in the Night" started revving up and Buckingham was pulled away, leaving Droman "kind of without a job all of a sudden," he laughs. Until late one night: Dashut called him up and beckoned him to a nearby studio, where Buckingham officially asked him to hop on the Fleetwood Mac sessions.

Meticulous, methodical and professional: "Tango" in the studio

Dashut, Droman and Buckingham formed a tight-knit triad to oversee the record's creation. The latter is a notorious perfectionist in the studio, but even for him, making "Tango in the Night" was an impressive display of stamina and fortitude.

For starters, Buckingham had developed some distinctive studio techniques that helped make the sound of "Tango in the Night" unique and different. Droman shares that one inspiration for this approach was the U.K. artist Kate Bush, whose records were known for their lush, expansive sound.

However, Buckingham's studio mad-scientist skills also prevailed. "The funny thing is, I don't think most people understood what we were doing — they thought it was samples and keyboards and stuff," Droman says. "And it wasn't: His deal back then was doing things at half-speed, or somewhere around half-speed. We came up with whole techniques for how to do that, and keep things organized.

"That's part of what makes this [album sound] open and airy, too. When you record something really slow and you speed it up, all the harmonics get shifted up. You end up with this high-end, this tinkly little high-end, that wouldn't exist [otherwise]. There's not another way you could get that, at least back then."

They also experimented with slowing down songs — which, say, would double the length of five-minute tunes. "Not only is it [then] a 10-minute song, but it's a brutal 10 minutes to listen to," Droman says with a laugh. "You're not listening to anything that's very much fun to listen to. We would do parts, and then double it and triple it and quadruple it, and each part would have maybe a little bit of a different tweak in the speed. That would give it a depth you wouldn't get normally, and a sort of chorusing effect."

Unsurprisingly, both Droman and Dashut stress that doing a record this way required an almost superhuman amount of patience. "We always used to joke that tedium is our lives," the former says. "That was our expression: 'Tedium is our lives.'"

Adds Dashut: "We'd just spend hour after hour, seemingly day after day, just on one part, two parts, because [Buckingham] had a certain way of doing it. And quite often we'd redo them the next day, because he wasn't quite happy with them. That was quite normal."

The intensity and long days made for an "isolating" experience for months on end, Droman says. "Back then, studios had no windows. We never even knew what time of day it was. You'd go out on the hall to go to the restroom or whatever, and all of a sudden, you realize it's nighttime — you've missed all the sun of the day."

To cope with the stress, he and Dashut would make it a point to grab breakfast, go golfing or build remote-control cars. The producer's personality also helped add levity and balance. "He was always there with a joke and a laugh, and kept the vibe a lot lighter than it would have been without him," Droman says. The pair would also coax Buckingham out of his house on Friday nights for dinner or a drink.

Still, the musician's focus (and confidence) rarely wavered. For Dashut, this changed the way he approached his role as producer.

"It wasn't like 'Rumours' or 'Mirage' or 'Tusk,' where I had to look over it and respond more to the performances and give instant feedback on an artistic level," he says. "With 'Tango' it was more, Lindsey had such a grip on it, and had such a vision of what he wanted to do, that at that point, my job became just nurturing him — or enabling him to do what he needed to do. And then, of course, add to it what I could based around which direction I felt everything was going.

"It's not like he needed anybody to tell him what was right or wrong, a producer in that way," Dashut adds. "Because he was very aware of what he was doing, whether it was right or wrong. He just needed more support. He needed a mirror, he needed some people to bounce off of.

"And at that point, that's more of what the production job became: enabling the artist to see his own vision, to realize their own vision. And that's what Greg and I tried to do with Lindsey, and pretty much succeeded with that."

Although Droman wasn't necessarily expecting such a trial by fire so early in his career, he saw the upside to the immersion. "Everyone was very sweet," he says. "Anybody would tell you who's worked with them, that band sort of takes over your life. At that time they did, anyway, as if you're part of their family and that's all there is to it, for better or worse. You're giving up your life to be in that camp."

Technology: A Help and a Hindrance

"Tango in the Night" was still recorded to analog tape, which allegedly amused at least one '80s new wave act: According to Droman, U.K. band Thompson Twins, which was also recording at Rumbo, called Fleetwood Mac "dinosaurs" for working on the medium. Yet the sound of "Tango in the Night" also incorporated some technology: Buckingham, for example, used a digital sampler called the Fairlight CMI to record various sounds and parts.

"It's funny, at the time I thought that was detrimental, even though I was all for the experiment," Dashut says of the Fairlight. "I loved, sonically, what it was doing. But I started to miss the old live feeling of the band — not that we did that with any of the albums live; they were all overdubbed — but still it all started off with the band in the studio playing together, as did 'Tango,' although not so much. But I think the Fairlight started replacing some of that human touch, some of the other band members. Lindsey was able to do a lot more on his own and control it a lot more artistically.

"I saw it as a double-edged sword," he continues. "[It was] both an innovative and a very exciting thing that was coming. But I also lamented the fact that the band didn't participate as much, as a whole. They were all going through personal things, especially Stevie. And it wasn't a particularly pleasant time in any of our lives, I don't think. It was a painful time."

This distance wasn't due to illicit substances, Dashut stresses. "Not many drugs — and by that time, the cocaine had pretty much gone, very little of that," he recalls. "Plenty of marijuana, I'm sure, which we always in use as an artistic tool. By then, thankfully the cocaine age had left for us."

However, the band members' private personal stresses manifested in other ways. For example, the band did overdubs on the record at Lindsey Buckingham's house. So as not to "invade his personal space and take over the inside of his house," Dashut says the group came up with an ingenious solution.

"They rented a huge RV, like a dressing room-slash-lounge, and they would hang out out in the driveway," he says. "And then they would come in and do their parts. It was kind of strange. It's not like everyone was hanging out together. They would take their turns doing their parts on the record. There wasn't as much togetherness, cohesiveness."

Droman recalls that the mixing sessions, also at Buckingham's house, were focused and meticulous. The crew worked with two analog machines ("Basically you're working with 46 tracks — I want to say pretty much every song was all 46 tracks," he says) and had to do a variety of quick maneuvers while mixing, including ensuring mutes were turned on and off at the right moments and faders were set properly.

"We mixed in sections," Droman says. "We would mix a verse, and then stop and reset everything and figure out what we were doing on the chorus, do that, and piece it together. We would take easily a week to mix a song. Sometimes we'd mix a song and Lindsey would think of another part he wanted to put on, and we'd start the whole thing all over again," he laughs.

The crew ended up deciding to use a new piece of equipment — a digital tape-based, two-track machine made by Sony — to capture the audio that would end up being mastered, since the digital tape preserved more detail.

"We expected to like the sound of the analog two-track machine better, since analog is known for being a 'warm' sound," Droman says. "But in this case, the Sony digital machine seemed to preserve what we liked about the sound of the original tracks better. The analog machine 'smeared' the sounds."

Because of the trio's working process, and the limitations of the then-new digital recording technology, sections of the delicate digital tapes had to be manually cut and spliced together. "The tape was really thin and hard to deal with, so I wore white gloves, and they used to laugh about that, because it looked ridiculous," Droman says.

Unfortunately, when the record was mastered, these splices started glitching, marring the sound of the record and causing panic. "We ended up putting the tapes in the refrigerator overnight," Droman says. "We tried everything, because we were freaking out. That was all we had; there was no backup or anything back then."

These glitches were eventually fixed for the finished "Tango in the Night," although Droman thinks he can still hear small remnants of the crisis. "There's something on one song — I think it's 'Little Lies,'" he says. "You could easily say 'Oh that's a hi-hat.' But it's not. I know it's not." He laughs.

Painful Endings and New Beginnings

Over time, the intense "Tango in the Night" sessions took a toll on Droman, and he started having panic attacks. "I didn't even know what they were," he says. "I think it was just the stress and long hours and so much of it. I couldn't tell what was going on. I was kind of freaking out."

After the record wrapped, he took a long while to decompress. "It took so much energy, and so much brainpower and stamina to get through it, that when it was over, I didn't even want to listen to it," he says. "When 'Big Love' would come on the radio, I would turn the radio off. I couldn't even hear it anymore." Still, there were absolutely no hard feelings. In fact, after leaving Fleetwood Mac, Buckingham tapped Droman to once again work on his temporarily abandoned solo record. (This LP eventually saw the light of day in 1992 as "Out of the Cradle.")

Fleetwood Mac, meanwhile, has done its part to help "Tango in the Night" reach new audiences. Stevie Nicks performed "Seven Wonders" on an episode of "American Horror Story: Coven," while Christine McVie rejoining Fleetwood Mac in 2014 ensured "Everywhere" and "Little Lies" returned to the setlist.

Dashut, meanwhile, remains fiercely proud of the record. "It absolutely holds up upon listening," he says. "It's probably one of my favorite Fleetwood Mac records, that and 'Tusk.'" Still, "Tango in the Night" ended up being the last project Dashut worked on with this configuration of Fleetwood Mac. Just as painfully, his long-term, close friendship with Buckingham dissipated after the record was completed.

Dashut would love to work with him again, however, and is leaving the door wide open for a reconciliation. "I miss him," he says. "I have to say, I really miss him. And I hope we do get back in touch in these next few months."

In fact, he has nothing but high praise for Buckingham. "I consider him on the level of a Brian Wilson, you know, Paul McCartney," Dashut says. "He's a genius; there's no way around that. And he's very well directed in his art, he's very opinionated. He's a true believer that art's not exactly a democratic process. It's usually done by one person with a vision: the artist. And I always saw myself as like the clownfish that could swim in the sea anemone and not get stung.

"He was tough to work with," he continues. "A lot of people are afraid of him. He could be brash; he could be harsh. He was very motivated. He always kept his eye on the prize, which is about quality music. That was the end-all, be-all: making a great record. And nothing would stop him. And if you would slow him up or impede that process in any way, you'd get run over. That was just what it is. Fortunately, the results proved him right."

Shares