As TV brand concepts go “Genius” is fairly brilliant. Each season National Geographic's new series, its first entry into the scripted realm, will choose one intellectual giant and spend multiple episodes breathing life and individual personality into biographies largely ordered and emphasizing their accomplishments.

Doing this in a way that meets if not matches the superior creativity and innovations set forth by the world’s greatest minds could result in an exceptional series that inspires as well as entertains. Should “Genius” achieve that level of greatness it’ll occur in future seasons. The series’ first, debuting Tuesday at 9 p.m., is merely serviceable.

That’s a shame given that the subject launching “Genius” is Albert Einstein, the 20th century’s face of high intelligence, whose theory of relativity ushered in the era of post-Newtonian physics. To the average viewer Einstein is science’s wacky uncle, a bushy-haired old guy impishly sticking his tongue out at millions of college students from posters adorning dorm room walls.

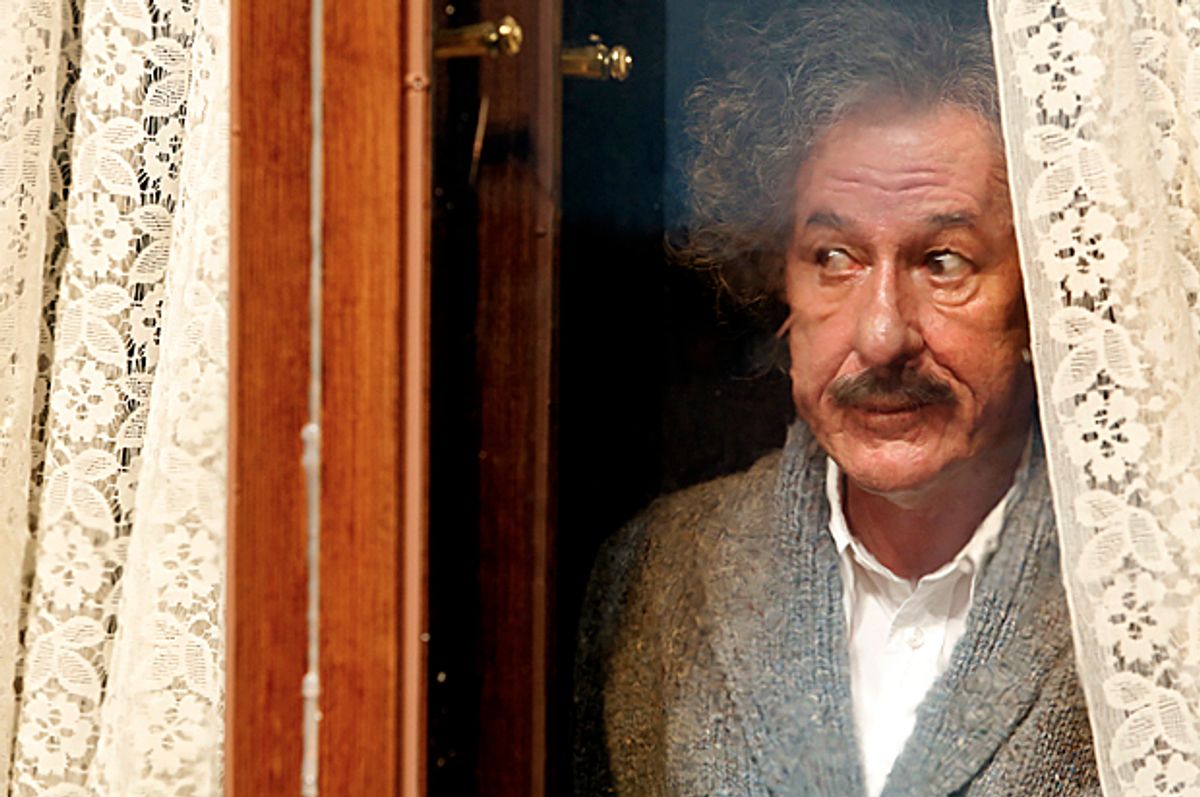

The channel’s 10-part series, though, makes its first attempt at revealing the human behind the ideas, by having us meet Einstein (played by Geoffrey Rush) mid-coitus. Pants-down, humping his assistant Betty (Charity Wakefield) against the wall, Einstein whispers sweet nothings in her ear in a sensibly ridiculous manner. Besotted, he reminds her in his professorial tone that monogamy is unnatural.

In turn, Betty reminds Einstein that his wife Elsa (Emily Watson) probably won’t see eye-to-eye with him on that issue. She shuts down the topic by angrily spitting, "For a man who is an expert on the universe, you don't know the first thing about people, do you?"

Betty receives limited exposure in the two episodes National Geographic made available to critics, and even within that short time one might appreciate that she is probably better than this leaden dialogue recited in many different series over the years to heroes of varying degrees of intellect. Betty’s not wrong, and the exchange isn’t out of place.

But this is one representation of the medium-height bar “Genius” sets early on in the series. Its scribe Noah Pink, who developed it with showrunner Ken Biller, took the biography of one of the rarest intellects humankind has ever known and transformed it into a drama that never rises above the level of merely good.

That could be enough for people who merely want to find out more about Einstein the man, but it’s difficult not to see the irony in a series about a man who prized imagination above all else is rendered in an entirely uninventive way. On top of that, it’s executive produced by Brian Grazer and Ron Howard, the founders of — what? — Imagine Entertainment.

Again, while “Genius” won’t go down in history as one of Howard’s highest achievements, he sets the table well enough in helming the opening episode, which travels through time with Rush’s mature Einstein anchoring the theoretical physicist in 1922 Berlin, and his younger, more impudent self, ably portrayed by Johnny Flynn, driving teachers and his father to the edge of madness in the late 1890s.

The youthful Einstein bounces between Germany, Switzerland and Italy and tests the limits of his teachers’ patience with his insistence on exploring theory as opposed to operating from the concrete truths of physics as imparted by Sir Isaac Newton and his adherents. If Rush’s performance is as good as he’s expected to be, Flynn is a revelation, injecting an insistent enthusiasm and recklessness into his interpretation of Einstein that gives the opening episodes of “Genius” a spark of life and humor.

In fairness, Rush is charged with a darker chapter, when belligerent thugs in brown shirts and swastikas became emboldened to harass Jewish citizens on the streets outside his home. In one such scene, the mature Einstein watches this unfolding horror while calmly coaxing melodies from the strings of his beloved violin. This brief snippet transcends the typical; without saying a word, Rush gives us a man so accustomed to taking the vastness of time, space and philosophy into consideration that the small, steady political maneuverings of lesser men did not concern him nearly enough.

Somehow both actors convincingly bridge the years between Einstein’s personas, as Flynn’s tics and comportment mirrors Rush’s naturally enough to enable audiences to easily buy their physical representation of the passage of time and evolution of space.

But the most revelatory performance comes from Samantha Colley as Einstein’s intellectual muse and first wife Mileva Maric. Colley’s steely confidence and caged vehemence dominates the Minkie Spiro-directed second episode, which sets Rush aside altogether to allow Colley and Flynn’s performances ample breathing room. And it’s here that Flynn shows us Einstein's inquisitive nature filtered through intellectual attraction, something we’ve yet to see in Rush.

The triumph of episode 2 is in its concentration on academia’s tolerance of Einstein’s rebellious streaks, contrasted with Maric’s constant struggle to be taken seriously. Colley viciously snarls whenever anyone attempts to break down the barriers Maric has built in order to navigate this world of egocentric men without sacrificing her dignity or composure, but her portrait is nevertheless beguiling.

Performances aside, very little about “Genius” captures the spirit of Einstein’s unique esprit or adequately translates the process of how his boyhood fascination with light beams grew into the theory of relativity. And while that’s not specifically required, it would be nice if “Genius” could solidify around a single concept beyond the life of its subject in its opening episodes.

Recall Howard’s Academy Award-winning 2001 film “A Beautiful Mind,” the story of a man whose outstanding intellect helps him to crack impossible codes. The film’s depiction of the way mental illness may have blurred the line of perception between the real and the illusory gave it its power. That may not be the most apt comparison, since Howard sustained criticism for portraying elements of its subject’s life inaccurately. But the director was able to defend the use of dramatic license, and surely Biller was free to employ it liberally here himself to give “Genius” a little more oomph. Because while Einstein’s life is truly interesting, the way he thought about the universe is the true source of our boundless fascination with him. The greatest works of television find a way to unlock that level of intimacy in their plots, but the secret to solving that equation may be beyond the scope of this show.

Shares