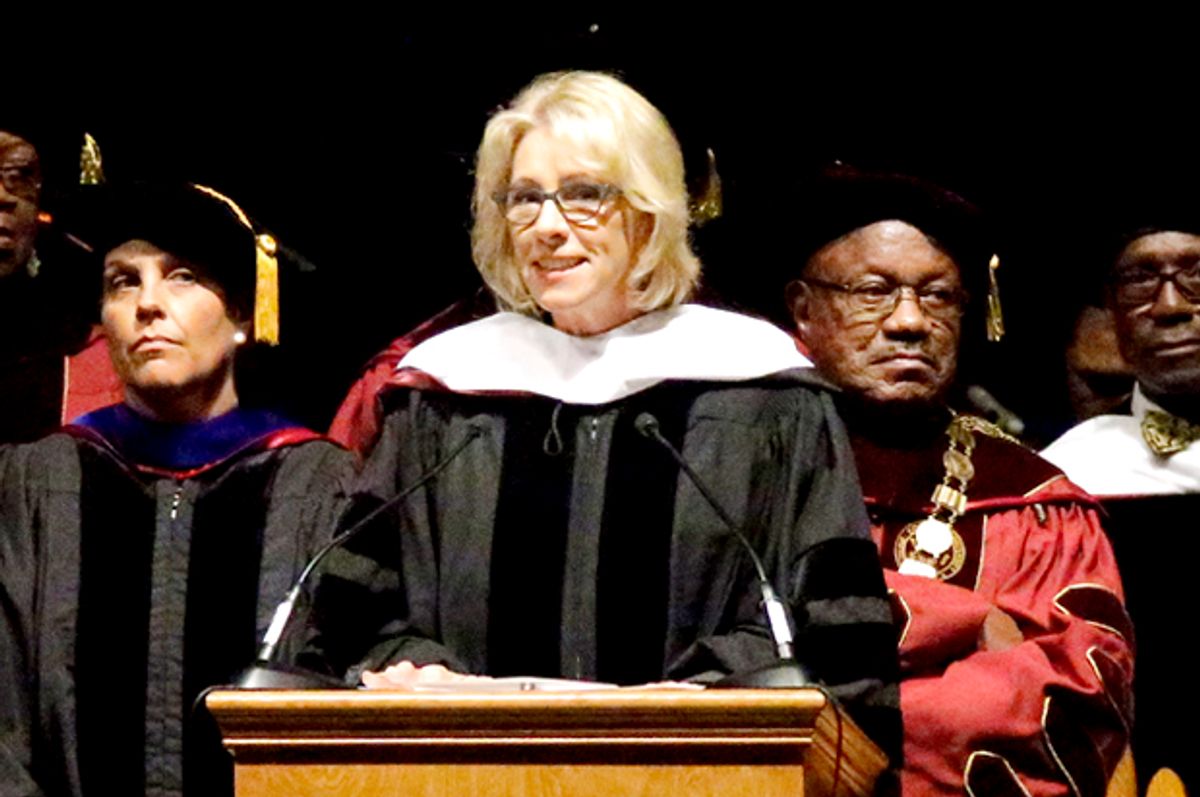

For those of us who care about education in our country there was something immensely gratifying about reports that Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos was booed when she attempted to deliver a commencement speech at Bethune-Cookman University. The fact that many students turned their backs to protest her appearance at the historically black school was additional just deserts.

Such behavior might be deemed childish or inappropriate or uncivil. And yet those conclusions must be mitigated by the reality that DeVos is such an outrageous insult to every value that shapes our educational system. Watching students openly protest a speaker who is anathema to the very foundations of their university was a welcome sign of pushback against the Trump educational agenda.

[salon_video id="14768893"]

DeVos is only one of many Donald Trump appointees to have a staggering lack of awareness of the institution she has been appointed to serve. Prior to her appearance at Bethune-Cookman DeVos had issued a statement that claimed that historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) “are real pioneers when it comes to school choice."

It was a jaw-dropping claim that erased the history of segregation in U.S. education and Jim Crow laws. HBCUs have absolutely nothing to do with “school choice.” They were founded before 1964, when segregation was legal and access to higher education was essentially nonexistent for black Americans. As the Los Angeles Times reports, the DeVos statement is "inaccurate and a whitewashing of U.S. history.”

But DeVos’s statement was even worse; it not only ignored the U.S. history of educational racism, it also ignored the reality that the students at Bethune-Cookman are products of the exact same public school system DeVos is attempting to dismantle. Fred Ingram, vice president of the Florida Education Association and an alumnus of the school pointed out that 90 percent of students who attend Bethune-Cookman were educated in public schools. ‘‘This is a woman who throughout her ‘career’ has condemned public schools, has said these are dead-end schools,’’ he said.

This is all to say that the shaming of DeVos is well deserved. She has been a force for destroying our public school system, especially in Michigan, and her role as Secretary of Education only gives her more power to advance her privatizing agenda.

And yet, it would be a mistake for us to allow ourselves to self-satisfyingly point the finger at DeVos as the sole culprit in the story. In fact, as University of California, Santa Barbara professor Chris Newfield argues in his new book, "The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them," we are all to blame.

Newfield explains that the increasing trend toward privatizing public higher education was aided and abetted both by universities and by the public they serve. This is so because as universities faced funding cuts, no one booed and no one caused a fuss. Instead, they adjusted and adapted and accepted the new status quo.

Since 2008 state funding for higher education has been in severe decline. Years of cuts have made college less affordable and less accessible for students. Though a handful of states have begun to restore some of the deep cuts in financial support for public two- and four-year colleges since the recession hit, in general support remains significantly below previous levels. A 2016 report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that, after adjusting for inflation, funding for public two- and four-year colleges is nearly $10 billion less than it was just prior to the recession.

These increased costs have led to decreased access and diminished success, especially for students from economically disadvantaged families. Newfield explains that “The United States is now nineteenth of twenty-three countries (the rich countries of Europe and Asia) in the proportion of entering university students who successfully graduate. . . . [T]wenty-four year olds in the lowest quartile of income have college graduation rates of 10.4 percent, or about one-seventh that of students in the top quartile."

Years of cuts in state funding for public colleges and universities didn’t only drive up tuition, they have also affected educational experiences by forcing faculty reductions, fewer course offerings, and campus closings. Despite the rhetoric that the privatized model offers students greater choice, these social “choices” have made college both less affordable and less accessible.

These drastic shifts are only part of the story, Newfield explains. The real tragedy is the way that the public simply accepted the long-term gutting of higher education. The general decline in public investment in our nation’s infrastructure, from roads to bridges to schools, has been constant. But the key, according to Newfield, is the fact that the public hasn’t pushed back and has accepted the privatizing trend in higher education. The “great mistake” has been the acceptance of a private-sector business model to a public good.

As John McGowan points out in his review of Newfield’s book, privatization takes costs that were once “socialized,” i.e. distributed across the whole population, and shifts those costs to the individual: “Once we lose the idea that higher education is a public good, one whose benefits rebound to everyone, then it is a short step to saying the good of an education is the benefit it provides to the student.”

The reality is that our society has so thoroughly internalized the idea that education is a private privilege and not a public need that the mere idea of affordable higher education as a social commitment we all invest in seems weird.

Recall that only Bernie Sanders had free public university as a part of his campaign platform. Prior to his call to make college affordable, no one on the campaign trail was even talking about it.

In general, cuts in funding have just been taken for granted. In contrast with Europe, where students often take to the streets to defend affordable higher education, in the United States tuition hikes go unprotested. Sure, the higher bills spark complaints, but these are localized. They don’t transfer into any form of collective resistance.

This lack of concern for the fate of the student is why our nation was able to elect Trump to the presidency even though he was being sued for fraud by students who had enrolled in Trump University. Trump settled the lawsuit in March of this year when a federal judge gave final approval to a $25 million agreement to settle fraud claims connected with Trump U, but the fact is that the lawsuit was well underway when he was elected. While it was only one of the many scandals that surrounded the Trump campaign, it is still noteworthy that allegations of student fraud didn’t keep Trump out of office.

Trump founded Trump University in 2005. The Washington Post reported in 2015 that he had to change the name in 2010 when the New York Board of Education accused him of “misleading the public by running an unauthorized school.” After that, the lawsuits and complaints continued rolling in. In 2013, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman announced he was suing Trump for fraud:

More than 5,000 people across the country who paid Donald Trump $40 million to teach them his hard sell tactics got a hard lesson in bait-and-switch… Mr. Trump used his celebrity status and personally appeared in commercials making false promises to convince people to spend tens of thousands of dollars they couldn't afford for lessons they never got.

As Mother Jones explained in its coverage of the complaints over Trump U, the instructors didn’t know the material, Trump was a no-show and the curriculum was a sham. Even more disturbing, Trump U rigged its course ratings, deceived students into thinking they were getting real degrees, and encouraged students to lie to credit card companies to increase their spending limits so they could get further into debt. Trump didn’t just offer students a privatized university experience; he totally took advantage of them, seeing them as a source of revenue rather than as a public investment.

The story of Trump U doesn’t just point out the horrifying ways that for-profit universities can and do use students to generate revenue, it also reminds us that the defunding of public universities has also led directly to astronomical levels of student debt. Forbes reports that student debt is now the second-highest consumer debt category — behind mortgage debt — and is higher than both credit cards and auto loans. There are more than 44 million student loan borrowers with $1.3 trillion in debt in the United States. Average student debt in the class of 2016 was $37,172.

What was once a public investment is now a private debt. And that transition only works if the public accepts it.

Perhaps even more disturbing is Newfield’s proof that “privatization,” which was supposed to bring “market discipline” to universities and thus improve efficiency and bottom lines, actually increases costs. Newfield examines the myth that the business model is one of efficiency and discovers that the more that business enterprise has seeped into university practice, the more costs for students have gone up.

Newfield thus puts a good bit of the blame for the “great mistake” on universities themselves. Despite overwhelming funding cuts, universities espouse the rhetoric of excellence and success. Not one university offers prospective students a brochure that admits that defunding has hurt their educational mission.

Refusing to admit these losses was a grave error, according to Newfield, because when universities suggested they could do more with less, they reinforced the idea that there was no need for public investment in higher education.

But that reality is truly astounding when you stop to ponder it. Newfield wonders how citizens could simply accept an 18 percent cut in public funding for the sort of medical research only performed at public universities. The cost of privatizing previously public forms of research means that rather than perform research in the interest of the public good, it is now often linked to corporate interests. And those federal grants that do roll in demand that universities also put in significant resources in the form of indirect costs to make the grants work. And yet, instead of calling attention to the negative impact of these shifts in research funding, universities boasted of their ability to attract external funding.

Rather than issue a rallying cry to the public to defend their mission, Newfield explains that “universities have asked people to marvel at their entrepreneurial prowess: they have raised tuition beyond inflation for decades, sought private donations, formed research partnerships” and more. Even worse, Newfield finds that universities lose money on grants, which don't cover costs: “universities, instead of bragging that their research losses are a donation to the welfare of humanity, have covered up [those losses] for decades.”

This is why booing DeVos may have a silver lining. Maybe our collective anger at her role as secretary of education can serve as a lighting rod to mobilize real resistance. Imagine what would happen if students and their families decided to organize a real political fight for affordable education. Imagine what would happen if communities marched for education the way they are marching for health care. Imagine if voters called on representatives to protect public education the way they are fighting to protect our environment.

Despite the fact that higher education is the one way we can train the next generation of scientists and political leaders and teachers and healthcare providers and more, there is a surprising lack of political will around the issue of defending our universities.

As the Trump team works to dismantle every aspect of our government’s commitment to care for the public, they are also offering us an opportunity to remind citizens that the bedrock of democracy is a strong public education system.

Critics will want to cast aside the student protests of DeVos as another example of intolerant identity politics. They will characterize the students’ outrage as that of shrill millennials who are whiny and entitled. They will talk about how DeVos’s free speech was curtailed.

But that doesn’t have to be the story. Instead, the protests at Bethune-Cookman could be the beginning of an organized effort to restore public commitment for our universities.

John Cassidy wrote a piece for the New Yorker almost a year ago musing about what the story of Trump U could teach us about the state of our democracy. As he put it back then: “If the revelations about Trump University don’t do any damage to Trump, it’s time to worry — or worry even more — about American democracy.”

Worrying isn’t enough, though. And while booing may be immediately gratifying, it isn’t enough either. As Newfield argues, what we need is a real commitment to restoring public education as a public good. That change has to start both on campus and off. If we don’t want the Trump U ideology to infect the last vestiges of our universities, we are going to have to do more than fight DeVos with a boo or a turned back.

Shares