Wedged between a pack of brunching moms in active wear and a disgruntled couple huddled over a plate of huevos rancheros, David Samuel Levinson inhabits Bubby’s TriBeCa like it’s his personal hell. Even his cobb salad —boring! disappointing! sad! — reflects a certain grim apocalyptic portent. He considers a lone piece of chicken as he eyeballs my pancakes and then regrets not ordering his own. The woman next to us complains about her housekeeper. Though it’s otherwise a beautiful, sunny day, the feeling that we are misunderstood aliens wandering in a world of robots pervades.

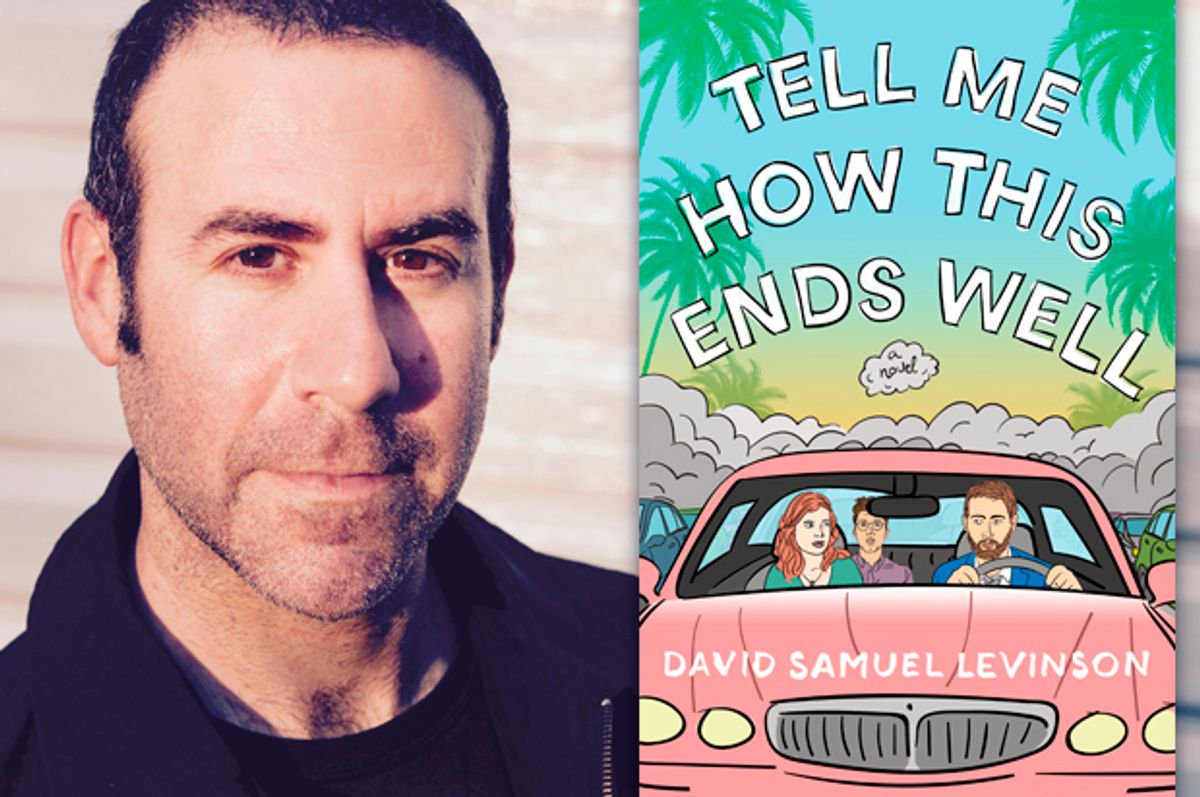

This feeling isn’t new. At least not for the Jews, for whom the notion of dystopia has been a reality since, well, the writing on the wall. For Levinson, author of the stunning and proleptic novel “Tell Me How This Ends Well,” dystopia, at least Jewish dystopia, is practically a preexisting condition, which is what drew him to set his novel in a near-future America wherein the state of Israel no longer exists and millions of refugees have relocated to the U.S., provoking virulent anti-Semitism and homegrown pogroms. Against this xenophobic backdrop, the Jacobson family gathers for a final Passover seder in Los Angeles before the death of ailing matriarch Roz. Driven by a shared resentment of their sadistic father, Julian, the three siblings conspire to end his life before he can end their mother’s and put a stop to his despotic rule once and for all.

“I may not be the first Jew to write a dystopian novel,” Levinson says, stabbing my pancakes with his fork. “Think of Roth’s ‘The Plot [Against] America’ or Kafka’s 'The Trial.’ So it’s timely and on another level it’s terrible and that’s the irony because as Jews we live in a constant state of dystopia. I wanted to write a book about terror and terrorism and anti-Semitism and how it pertained to a particular, dysfunctional Jewish family in the U.S.A. The terror outside, in some ways, isn’t half as bad as what goes on in their minds.” He shrugs, as if to say, what isn’t.

So what, exactly, comprises dystopia in the deranged landscape of 45? Why read one or watch one – think Margaret Atwood’s “Handmaid’s Tale” on Hulu or Neil Gaiman’s “American Gods” on Starz – if you’re already living in one? Is it a dire necessity, cold comfort or a hat on a hat on a hat? While Gaiman told the New York Times that “speculative fiction usually ages very badly,” in his case, not so much. For Levinson, these questions are tantamount to a philosophical exploration of what it means to live as a Jew in a world gone mad — in other words, what constitutes the “normal world” for the non-marginalized. Politics and world-building aside, if dystopia is philosophy made flesh then “Tell Me How This Ends Well” does for the Jews what “American Gods” does for our pagan ancestors: It pits father and son in an epic battle for the soul of America as it asks both the question, Can good people do bad things and Can bad people do good things. Beneath this dystopian chiasmus, is brutal and often hilarious satire and nightmare visions of death on the 405.

“I looked at current events like the toppling of gravestones and bomb threats of synagogues and I took them to their logical end,” Levinson continues. “I had empirical proof that rampant anti-Semitism only goes in one direction – the death of 6 million. So ‘1984’ and ‘Handmaid’s Tale’ weren’t prescient as much as cautionary tales about what our future will look like.” He leans in to whisper. “By future I mean the present. It’s bleak, Mary.”

“'Dystopian’s' not a word I would use to describe ‘American Gods,’” Bryan Fuller, co-creator of “American Gods,” tells me over the phone. “But both ‘Handmaid’s Tale’ and ‘American Gods’ are looking at extremism and faith in a really different context. In ‘American Gods,’ there’s something about old ideas rising up to fight for belief and religious tolerance. In ‘Handmaid’s Tale,’ the old extremists punish the liberal, thinking populace out of spite and fear and that’s what’s happening in America now.”

In truth, “American Gods” depicts the transgressive atmosphere synonymous with dystopia: constant motion and menace, illicit behavior (good people doing bad things) and the identity crisis and unease that gripped the country not only at at the end of the millennium, but also as far back as the early settlers. (Think “Running Man” meets “The Brothers Ashkenazi.”) A descendant of Polish Jewry via London, Gaiman moved to the Midwest in the '90s and wrote “American Gods” to make sense of this newfound goodly, godless environment. Not only does his protagonist Shadow have a criminal past, but he also aids and abets Wednesday (Odin) in acts of lawlessness that align with the general mise-en-scène of the narrative; everyone’s transgressive and up to no good, though, if you’re lucky, Yetide Badaki might just stuff you up her hoo-ha.

“You’re in the perspective of Wednesday in this battle of old gods versus new,” Michael Green (co-creator) says. “You think his enemies are your enemies and that they’re the bad guys but then you learn it’s not inherently wrong, it’s just philosophically different.”

Conversely, for Atwood and Levinson, Götterdämmerung is a clear and present danger where the bad guys are as obvious as the side you are meant to take. While “The Handmaid’s Tale” depicts a government-sanctioned female slavery and rape culture where women are deprived of hand lotion, Margaret Atwood based the novel’s fundamentalist government of Gilead on totalitarian communist regimes as well as the mob mentality of the United States’ Puritanical roots. The resulting theocracy that Offred (Elisabeth Moss) navigates is one of red shrouds and paranoid doublespeak. First Planned Parenthood and next The Flying Hun.

“We write what’s important to us,” Levinson acknowledges, then pours syrup on a pancake. “I write about anti-Semitism. Atwood wrote about reproductive rights. Of course, we both never thought it would sprout wings and grow hair! I would like this book to be a cautionary tale about domestic abuse and anti-Semitism with a message that says, ‘Be nice to your kids or they’re gonna kill you.’”

Shares