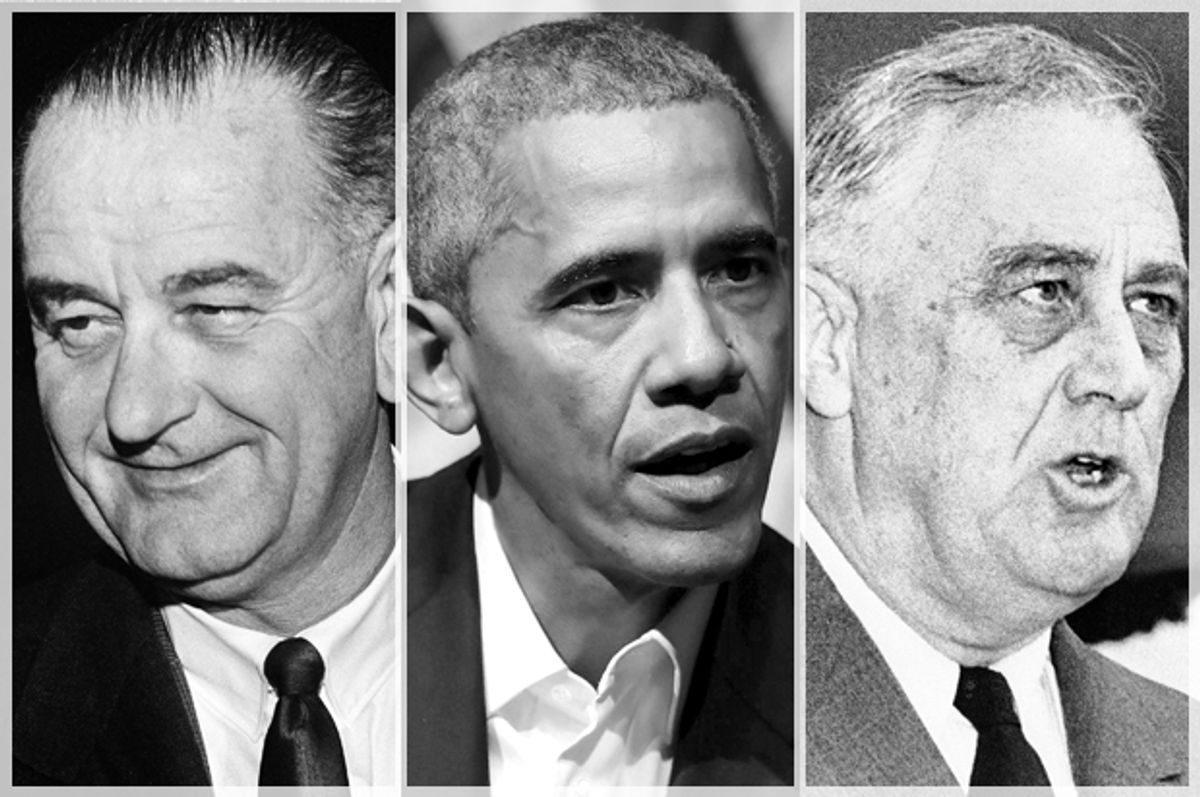

If nothing else, the Republicans' repeated failure to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act – colloquially known as Obamacare — is a testament to the fact that, for the first time since Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson, Democrats had a president who was able to pass successful and lasting progressive legislation.

If Americans are going to understand the dilemma in which the GOP currently finds itself, it will thus be helpful for left-wing Democrats to learn from what Obama and other productive Democratic presidents like him have done right.

This isn't to say that the ACA is a perfect bill. As Steven Rosenfeld of AlterNet pointed out in 2015, "Obamacare is not the long-sought dream of universal health care — a right, not a privilege or a profit center." Like most major domestic legislation, the ACA is a complex behemoth of a law, and as a result it is easy for those inclined to criticize it to find faults that justify their preconceptions.

Yet the bottom line is that America is a better place to live because the ACA was passed. It has expanded insurance coverage to roughly 20 million Americans, lowered costs for the 57 million Americans who use Medicare and made it illegal for insurance companies to deny coverage based on preexisting conditions or increase charges for the sick. There are literally millions of people whose lives have been improved, and almost certainly lengthened, because of the law passed by Congress and signed by President Barack Obama in 2010.

That is why Republicans have so far been unable to pass their much-promised Obamacare repeal. The dilemma in which the party has repeatedly found itself is that, in order to repeal the law and replace it with something substantially more conservative, they would need to rip health insurance away from roughly 22 million people.

It's still possible that Republicans can find some replacement that can win adequate support from both the moderate and conservative factions of the party -- although the patchwork Senate bill crafted behind closed doors by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell didn't even come close. But it is increasingly unlikely that the GOP can do so in a way that completely wipes out the ACA's legacy. Although Republicans clearly thought of repealing and replacing Obamacare as simply a way to score political points, it has become unavoidably clear that eliminating the law would literally cost human lives.

That's so important that it bears repeating: Republicans have found themselves unable to repeal Obamacare, at least to the extent that they clearly wanted to, because doing so would cause people to die.

Considering that the people who would die without Obamacare are many of the same ones who would have died had it never been passed, this is a testament to the bill's success as both policy and political instrument. It also places it in the same category as many of the New Deal programs passed under Roosevelt, and the Great Society and War on Poverty programs passed under Johnson.

The analogy between Obama, on the one hand, and FDR and LBJ, on the other, is not perfect, of course. Roosevelt and Johnson both achieved wide-ranging social and economic reforms, with lists of legislative achievements so extensive that they wound up requiring terms of their own (i.e., the New Deal or the Great Society). Roosevelt's lasting legacy included banking regulation, job creation, labor protection and programs like Social Security that endure today. Johnson's includes Medicare, Medicaid, consumer protection, environmental regulation and civil rights programs that are also still being felt throughout America.

By contrast, Obama's social agenda was either inherently transient by nature or doomed to be repealed. His main piece of financial regulation, the Dodd-Frank Act, is already en route to being rolled back, and although his stimulus law did manage to stave off a second depression, its direct impact on the American people has largely fizzled since its implementation. Beyond those two bills and the ACA, the Obama social and domestic agenda becomes more modest and comparable to those of the modern Democratic presidents besides FDR and LBJ, rather than equivalent to their landmark achievements.

In addition, as noted earlier, Obamacare has some serious flaws in its own right. It does not achieve universal health insurance, it does not include a public option and it was in many ways a boon to insurance companies (which was politically necessary in order to win the votes of conservative Democrats like former Sen. Joe Lieberman). Conservatives have also pointed out that the law's mechanisms and regulatory structures are complex to the point of being confusing, and they are not entirely wrong.

At the same time, to paraphrase the late Sen. Ted Kennedy, it is imperative that progressives not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. If Obamacare truly wasn't a major achievement in history, Republicans could easily have repealed it and replaced it with a law of their own devising. It is a true testament to the historical significance of this bill that an outright repeal would be devastating to so many Americans -- not to mention so politically toxic -- that the GOP simply can't afford to do so.

Whenever and however Democrats can regain power, they should remember the lessons of Obamacare. It was an undeniably imperfect compromise, one that made the lives of Americans better and created lasting change.

Shares