Who are the crazy people who go to North Korea? My parents are some of those crazy people.

North Korea and its inhumanity is in the news yet again after the death of Otto Warmbier, the boy-next-door college student who was detained there after taking down a poster, returned home in a coma and died earlier this month.

Why would anyone want to visit such an unpredictable and hostile place? Some want news footage that might have led to professional glory. Others want to evangelize their religious beliefs. Others may go to boost their reputations as a daring adventure traveler. Many of us cannot help but to think that those unlucky Americans detained there have some streak of compulsive insanity that they went in the first place.

My parents do not fit that stereotype. My father went because he missed the place. My mother tagged along.

My father’s life began on a family-owned peanut farm on the border of North Korea and China. He recalls expansive fields, communal living with extended family and endless cousins as playmates. He is nostalgic about running in the fields, seeing the horizon and playing practical jokes on the farmhands.

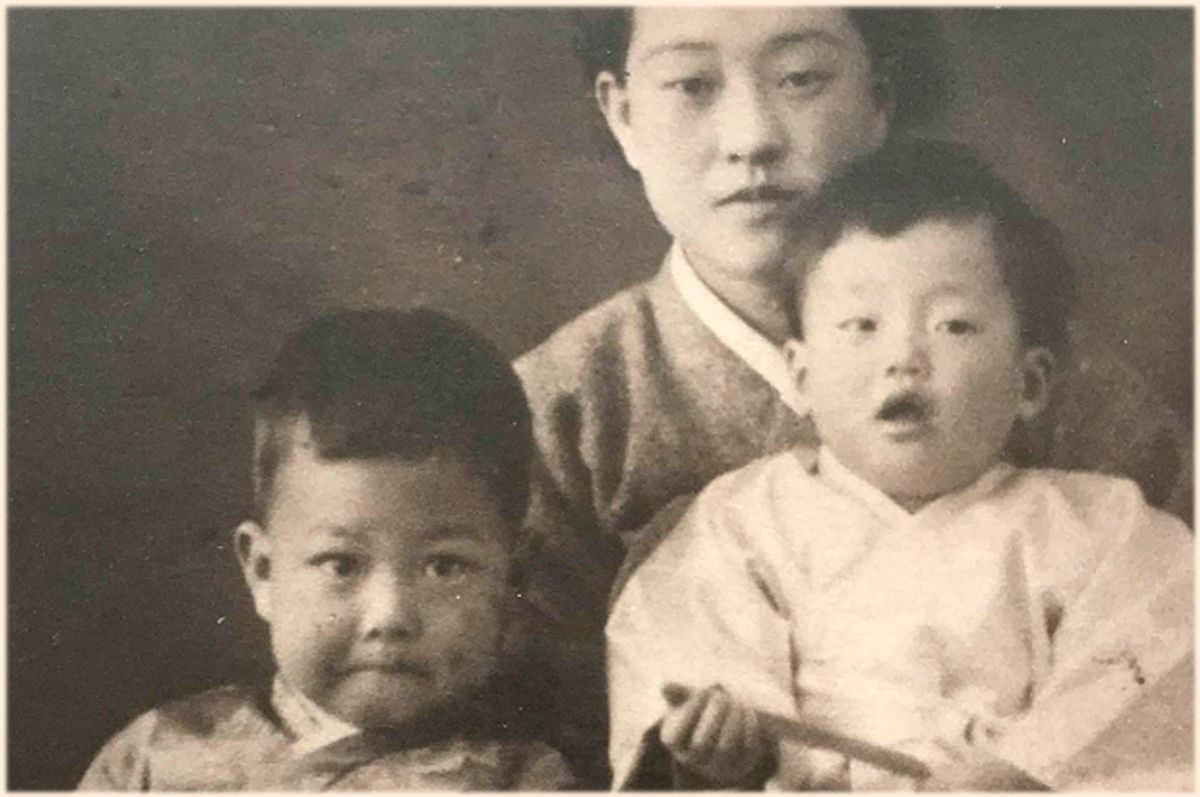

That ended suddenly. As a seven year old, he was sent to his uncle’s house and by foot, fled the invasion of communism and dictatorship by North Korea and its allies. As the eldest son of his immediate family, he was quietly sent by himself. His four sisters, younger brother, and parents remained behind to avoid bringing attention to their land-owning family. A year later, his penniless family caught up with him in the south, except for his brother who died of measles on the way.

My father became a surgeon and has lived in the United States since the 1960s. He listens to country music and has been an American citizen for 50 years. But he missed the land and the people of North Korea, which he always managed to see as separate from the brutal dictatorship. So four years ago, my father emailed me the name of his lawyer who managed his will, then he and my mother joined a medical mission originating in China, and crossed over the Tumen River into North Korea. I did not question their decision or try to stop them. I knew I would have no influence over them.

“Hosts” met them as soon as they arrived in North Korea. Each person was assigned a host. Some call them “minders.” They accompany visitors everywhere and direct every aspect of their movements. My father’s host even sat in on a few surgeries my father performed on high-ranking government officials and their families. I expected my parents to say that their minders were polite, efficient, offered rehearsed answers to questions and avoided friendship. Instead, my father had a very different story describing his surveillant who was not much younger than he.

Over time, my father and his minder had developed some type of relationship I had not expected. My father’s ability to recall the North Korean dialect, but only in the familiar, informal vernacular, probably allowed a stunted and restricted type of friendship to begin. I am not sure the North Korean government would have approved.

They began to share meals and enjoy each other’s company. They shared childhood stories, talked about foods and flavors. They exchanged family stories, too, although it is not known if the minder’s stories were true. They drank alcoholic beverages together and sang childhood songs. On the last evening there, my father bought two very expensive bottles of spirits. They drank one together and he gave the other to his host as a gift. They sang more songs while swaying back and forth with locked arms. At the end of the night, his host held my father’s hands and cried. “You will come back, won’t you? Tell me you will come back.”

At this point in the story, I felt second-hand pain and sorrow through my father, who had started crying. He is a trauma surgeon. Refugees who become trauma surgeons rarely cry.

He had the chance to see his birthplace and its people one last time. But the resolution he had hoped for is impossible. My father left there with some survivor’s guilt. My father and his minder both started life in North Korea and sang the same childhood songs. The vast majority of people there are no different from us. The fact that my father escaped and his minder was trapped was an accident of fate. It would have been easier if his minder fit the stereotype. Instead my father left North Korea haunted by the humanity that still survives there.

There will be no visit back to North Korea. He will never see the peanut farm of his fond memories. He will never again hold hands, laugh, cry or speak to the people who used to be his neighbors and friends. He is never going back. He cannot go back.

Shares