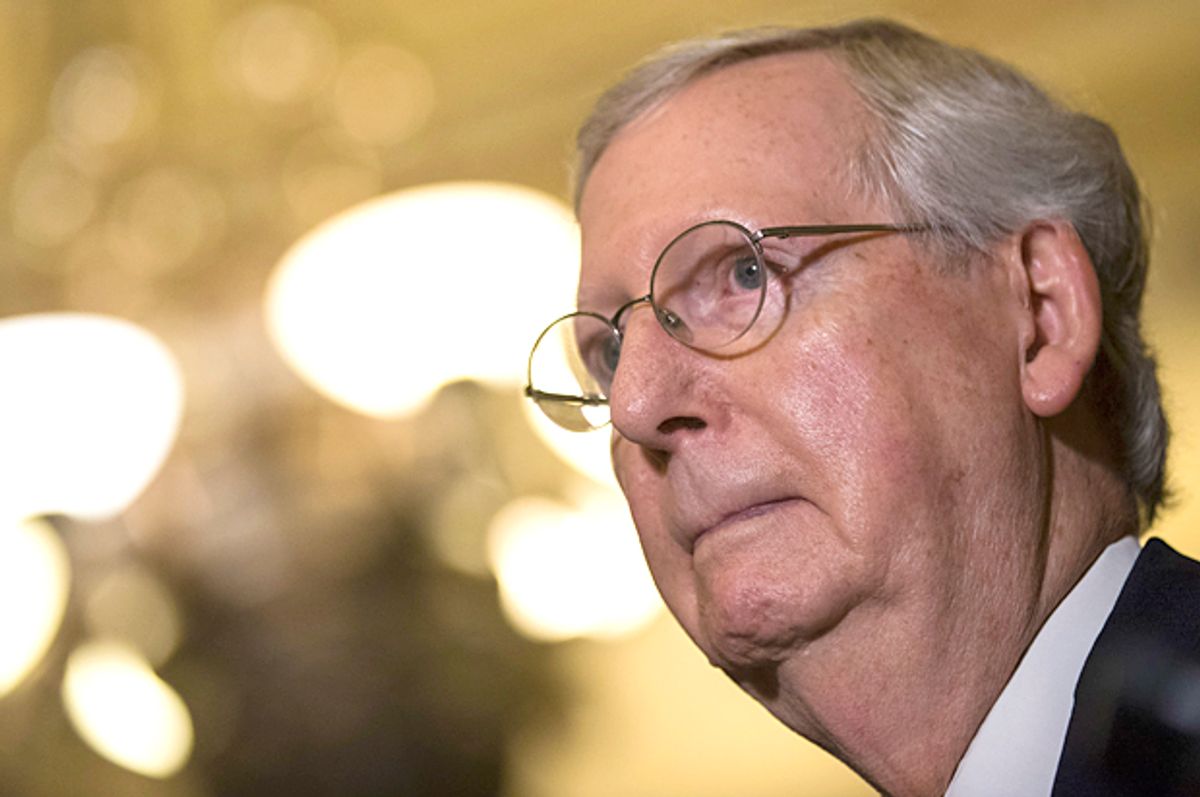

It's becoming clear that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell's plan to decimate the American health care system is to tinker around the edges of his bill until, as Charles Pierce of Esquire argued, "you get a CBO score you can plausibly use to con the country, the elite political press, and the mind of Susan Collins into thinking you're 'moderating' the bill." McConnell is counting on the fact that the press is easily bored and always eager to move onto the next new thing -- often meaning whatever President Trump has just said on Twitter -- and all he needs is a week of such distractions to pass this stinker under the cover of darkness.

But don't let the tinkering or assurances that the health care bill is somehow becoming more moderate fool you. Republicans still plan on passing a bill that will lay waste to the protections offered ordinary Americans in the Affordable Care Act, leaving people vulnerable to financial ruin or even death from illnesses or conditions that are covered under existing law.

One of the ways Republicans plan to do this is to gut the part of the Affordable Care Act that guarantees coverage of what are deemed "essential health care benefits." That sounds like a minor bureaucratic adjustment, but in reality it's a back-door way to deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions, limit important and life-saving health services, and force people with expensive conditions to go bankrupt rather than rely on insurance to cover them.

The essential benefits that the Affordable Care Act delineated include 10 categories of care that every insurance plan has to cover. Some of these categories are straightforward things that most insurance plans, whether purchased on the individual market or provided by employers, already covered, such as hospitalization or doctor's visits. But, as Timothy Jost, a professor at the Washington and Lee University School of Law and an expert on health care law, explained in an interview, prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act many individually purchased plans skipped major categories of coverage.

“What they didn’t cover was maternity care, mental health and substance use disorder care -- and often prescription drug coverage was quite limited," Jost said. “The ACA also added habilitation care for special needs children.”

Under various versions of the Republican plan, states would be able to apply for waivers to exempt plans sold in their state from this mandated list of essential health care benefits. Republicans have repeatedly insisted that their bill bars discrimination against patients with pre-existing conditions. But as Jost explained, ending essential health care benefits creates a mechanism that allows insurance companies to deny coverage of those pre-existing conditions. You'd be allowed to buy insurance, but it might not pay for the things you really need it for.

"So you got a mental health problem, sorry, we’re happy to insure you, but we don’t cover mental health problems," Jost said, describing the logic. "You’ve got cancer? We’re happy to insure you. We don’t cover any chemotherapy drugs or we don’t cover radiation therapy.”

Presumably, the reason Republicans want to cut essential health benefits is to lower premiums — which is why we get to hear Republican politicians making cracks about how men don't need maternity care — but Jost said he believes the mandatory benefits "are really a very small part of the total cost of coverage.”

For instance, as Jost has argued on the Health Affairs blog, ending mandatory maternity coverage "might lower premiums by $8 to $14 per month," but would force women who are giving birth to pay as much as $30,000 to $50,000 in out-of-pocket expenses.

Most of these effects would be felt by people who buy insurance on the individual market, or who work for small companies employers that offer less expensive plans with skimpier coverage. As Matthew Fiedler, a fellow with the Center for Health Policy in the Brookings Institution's Economic Studies Program, explained, there's a poison pill buried in the bill that would also affect people who work for large employers that offer more generous health insurance packages. Repealing mandatory essential health care benefits would mean reintroducing lifetime limits or annual coverage caps for many people on those plans. Which means that a lot of people who thought they had generous, comprehensive insurance plans could still face bankruptcy in the event of a serious illness or accident.

Under the ACA, Fiedler explained, "Insurers can’t put lifetime or annual limits on types of care that are considered essential health benefits. But they can put lifetime or annual limits on things that aren’t essential health benefits. What that means is that when the definition of essential health benefits changes, that can substantially change the scope of the protection against annual or lifetime limits."

Even if you live in a state that sticks with the old Affordable Care Act definition of essential health benefits, you may not be protected if you work for a large employer, defined as any company or entity with 50 or more employees. That's because, according to Fielder, a large employer can choose any state's definition of "essential health benefits." It doesn't have to stick to the state where it does most of its business, or where its employees actually live.

“Employers could choose a state that had implemented a very lax definition of essential health benefits and thereby have fairly broad latitude to impose these kinds of limits," he explained.

So a worker in a state like California or Massachusetts, which is likely to continue to protect essential health care benefits, might find that her employer has instead chosen define essential health care benefits under the terms set by Texas or Mississippi. So while that person's policy might still cover cancer treatments or maternity care or mental health services, she might find out that in practice her insurance company will not cover nearly as much of the cost as it would have under the ACA.

Because of the ban on lifetime and annual limits, the cap on out-of-pocket spending for patients, and the ban on discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, the Affordable Care Act was able to cut the number of personal bankruptcy filings in the United States by half between 2010 and 2016. By drafting a way for states to opt out of the essential health care benefits mandate, the Republican bill will potentially allow insurance companies to dump those costs back onto the consumer. The number of medical-related bankruptcies could well soar back to pre-Obama levels -- if Mitch McConnell can find a moment when we stop paying attention and ram this bill through the Senate.

Shares