A specter is haunting the Democratic Party. In a roundabout way it could indeed be the specter of communism, because so many of the party’s problems result from the long and toxic hangover of the Cold War. (If anyone actually “won” the Cold War, I’m increasingly sure that it wasn’t “America,” unless that noun is understood to refer exclusively to the capital-owning class.) But that’s a longer argument than I intend to make here. The specter I have in mind is Hubert Humphrey.

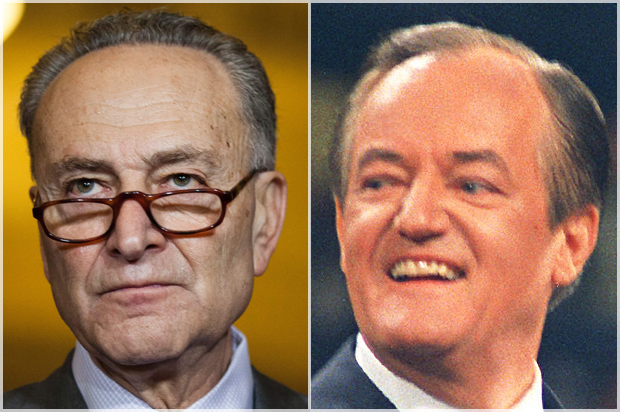

Watching Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer in action this past week in Washington — pulling off what was either a major political and policy-making masterstroke or a potentially fatal compromise, depending on where you stand — put me in mind of Humphrey in various ways. I am reasonably sure that Schumer, a student of political history if ever there was one, would be flattered by the comparison, though I’m less certain about whether he should be.

No one below middle age can plausibly remember Humphrey’s career first-hand, or is likely to understand how famous he was. After announcing that he had terminal cancer in the fall of 1977, Humphrey became the non-member and non-president to speak to the House of Representatives. President Jimmy Carter gave him command of Air Force One for his last trip to Washington. When Humphrey died of cancer in January 1978, he was accorded one of the most illustrious political funerals of any non-president in American history. (It was probably the only occasion when Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter were all in the same room, at least subsequent to Nixon’s resignation.) Humphrey had a long and distinguished Senate career and ran for president four times; only his illness stopped him from going for No. 5 in 1976. (He believed he would have won, but then he always did.) Only one of those campaigns is remembered today.

Humphrey and Schumer, leading Democratic insiders of different eras, are also very different in terms of background, personality, style and ambition. Humphrey always believed he would be president, which may have led to his downfall; I doubt Schumer has ever harbored such delusions. Both came from middle-class striver families with immigrant roots, which is no doubt relevant to understanding their political careers, but the circumstances were far apart: Humphrey grew up above his dad’s drugstore in a South Dakota town so small it literally dried up and blew away; Schumer’s dad was an exterminator in a Jewish neighborhood of Brooklyn. (He was valedictorian at James Madison High School, which is also the alma mater of Bernie Sanders and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Their debate team must have been something.)

Humphrey and Schumer are both avatars of bipartisanship and compromise, who excel at the kind of dealmaking with adversaries that is (or at least used to be) the substance of legislative accomplishment in Washington. Both are or were also eager to present themselves as men who combined those political skills with bedrock principles, although you’d have to say that argument is stronger in Humphrey’s case — at least until you get to the fiasco of the 1968 presidential election. What are Schumer’s principles, exactly? He has been a foreign-policy hawk (especially but not exclusively on Israel) and a major booster of the Wall Street investment banks throughout his career, so his newfound bi-curious identity on progressive issues definitely comes with an asterisk.

I’m not saying the prairie populist and the Brooklyn macher have some fundamental kinship, beyond being good at politics. It’s more that the historical and political relationship between them has a curious and compelling symmetry. Schumer may be trying, consciously or otherwise, to be Hubert Humphrey in reverse. That is, he’s trying to heal the enormous Cold War rift that Humphrey opened up in the Democratic Party’s heart as its ill-fated presidential nominee in the disastrous year of 1968.

Humphrey lingers on in the 21st-century political memory almost entirely because of that year, as a footnote or symbol signifying the factional division that tore the Democratic coalition apart nearly a half-century ago and — again, depending on where you stand — has done so several more times since then. In this context, Humphrey is the prototype for Hillary Clinton in 2016 (and for Al Gore in 2000): He was either the Establishment hack who exposed the Democrats’ ideological bankruptcy, or the qualified and pragmatic liberal whom the purist snowflakes of the left refused to support.

Humphrey was the first solution to this simplistic equation: OMG if only you losers had gotten over yourselves and voted for X, we wouldn’t be stuck with unbelievably horrible Y right now! That’s simplistic for a whole bunch of reasons: It rests on unproven and indeed unspoken assumptions — most notably the idea that person X lost because of intransigent left-wing holdouts, rather than for other reasons — and it declines to ask how we wound up with this choice (and this kind of choice) in the first place.

When I perceive a complicated relationship between Humphrey and Schumer, I don’t really mean that Humphrey, the sitting vice president and political operator who stole the 1968 Democratic nomination in a blatant backstage coup (he hadn’t won any primaries, or even run in any) and then trapped himself in the role of right-wing Democrat, Vietnam War apologist and enemy of the counterculture and the student left. As it happens, Chuck Schumer was an undergraduate at Harvard during that tumultuous year, and like his future friend and colleague Hillary Rodham Clinton at nearby Wellesley, he campaigned for Eugene McCarthy, Humphrey’s distinctly Bernie-like left-wing rival.

As Schumer is certainly aware, there was a cruel historical irony to Humphrey’s Waterloo moment of 1968, because for decades — as a U.S. senator from Minnesota and before that as mayor of Minneapolis — Humphrey had been one of the Democratic Party’s leading progressives, a staunch supporter of civil rights and an advocate of nuclear disarmament. Indeed, during Humphrey’s early career, he sought to narrow the gap between the party establishment, then still reliant on corrupt urban political machines and segregationist Dixiecrats, and the activists on its leftward edge. That’s very close to what Schumer is trying to accomplish right now.

It was Humphrey who told the Democratic convention of 1948, 15 years before Martin Luther King Jr.’s march on Washington, that it was time for the party to “get out of the shadow of states’ rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.” (Delegates from Mississippi and Alabama walked out of the hall; some Southern Democratic senators shunned him for years.) He was instrumental in creating the Peace Corps, enacting Medicare and passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Humphrey was an ardent anti-Communist and also the paradigmatic Cold War liberal, believing that the best way to fend off the Red menace was through strong labor unions, progressive social policies, redistributive taxation and an expanded welfare state.

We can’t possibly know what Humphrey would have made of the Democratic campaign of 2016, and he was a party loyalist to the core. But if the Humphrey of 1968 faced a political quandary similar to that faced by Hillary Clinton last year, that’s where the parallels stop. The Happy Warrior might have found Bernie Sanders’ rhetoric overly inflammatory, but on the major issues and central themes he would have agreed with Sanders right down the line. Hillary Clinton’s positions would likely have struck him as a baffling and incompatible blend: a civil-rights Democrat with an oddly constricted social vision; a free-market Republican slightly to the right of Nixon, but without the racism.

Perhaps Humphrey fatally misjudged the political climate of 1968, and perhaps he was cornered in a no-win situation under a failing president and an unpopular war he felt obliged to defend. (Numerous books have been written about that election without resolving that question.) At any rate, his reputation as a principled progressive who could unite idealistic leftists, party regulars and lunch-bucket Democrats — the Sanders, Clinton and Trump demographics, as we would say today — was poisoned forever.

Chuck Schumer has probably never struck anyone, including his teachers back at Madison High, as a principled progressive. But he may be trying to reverse-engineer the Democratic Party’s ideological split by coming at it from the other direction. Everything he has done since Donald Trump’s election victory suggests that he wants to narrow the policy differences between the Sanders and Clinton wings of the party to the point where they stop mattering to most people, without compromising his ability to (let’s just say) cut a private deal with an unpredictable president that leaves the Republican leadership suddenly feeling as if they had left the house without pants.

As Democratic consultant and onetime Schumer aide Michael Tobman told me a few days ago during a Salon Talks conversation, his former boss probably doesn’t support single-payer health care or a $15 minimum wage, or at least does not think they’re achievable anytime soon. But it costs him nothing to assure the Berniecrats that their treasured policy goals are legitimate topics of discussion (something Clinton was reluctant to do during the 2016 campaign). Similarly, it cost Schumer nothing to support Rep. Keith Ellison, a Sanders ally, over Tom Perez during the recent Democratic leadership contest, especially if he calculated (as seems likely) that Perez would win anyway. To use a Clintonian phrase, Schumer is triangulating; but for the first time in recent history, he’s triangulating his party at least a smidgen to the left.

For all the other things he did, many of them good or noble or at the very least sincere, Hubert Humphrey’s enduring legacy is as the well-intentioned liberal who blundered into catastrophe, blowing up America’s then-dominant political party and sending it into a tailspin from which, in many ways, it has never recovered. Perhaps Chuck Schumer sees the final act of his political career as being the calculating centrist who understands how to patch that hole, in early Humphrey style, by forging a truce between neoliberals and the activist left and resetting the Democratic trajectory back toward victory. I think it’s genuine political genius. That doesn’t mean it’s going to work.