“The border between the States and Mexico is not a borderline. It is a scar,” Bruce Springsteen explains, quoting Carlos Fuentes from the stage, near the end of his March 19, 1996 performance in Belfast on The Ghost of Tom Joad Tour.

Springsteen, the quintessential working class rock ‘n’ roll troubadour, broke from both his white worker protagonists and his medium of “blues verses and gospel choruses,” as he often calls it, in the mid-'90s. After moving to California, he turned the grandeur of his poetic vision and attuned the artery clearing blunt force power of his guitar strings to another story of struggle, but one far removed from the streets of New York and the small towns of New Jersey. He summoned the tenderness and toughness of his serenade to broadcast the hardship and heartbreak of Mexican immigrants — men and women who risk dehydration, murder by human coyote, and detention in dirty jail cells to traverse across the scar separating Mexico and the “American dream,” all in the hope — sometimes reasonable and just as often futile — of providing a better life for themselves and their children.

Not an economist, historian, or journalist, but simply a singer, Springsteen understood what still eludes many politicians and millions of Americans committed to the optical challenge of the blindfold. The Mexicans who moved to America, legally and illegally, in the 1990s, were not only “undocumented,” but the subjects of an unacknowledged forced migration.

The North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement demolished the livelihoods and damaged the lives of five million Mexican agricultural workers. Having lost their only means of scratching and clawing out an income in an already impoverished country, many of these former farmers followed the expropriation of their wealth to its new home, the United States of America. What they would often discover is that the prize at the end of their scavenger hunt was elusive. Caught between the rock of exploitative employers in a wealthy nation that was willing to use them but not welcome them, and the hard place of infertile soil at home, they traded one form of pain and desperation for another. Some succeeded, giving demonstration to a quiet heroism, and others died face down in the desert.

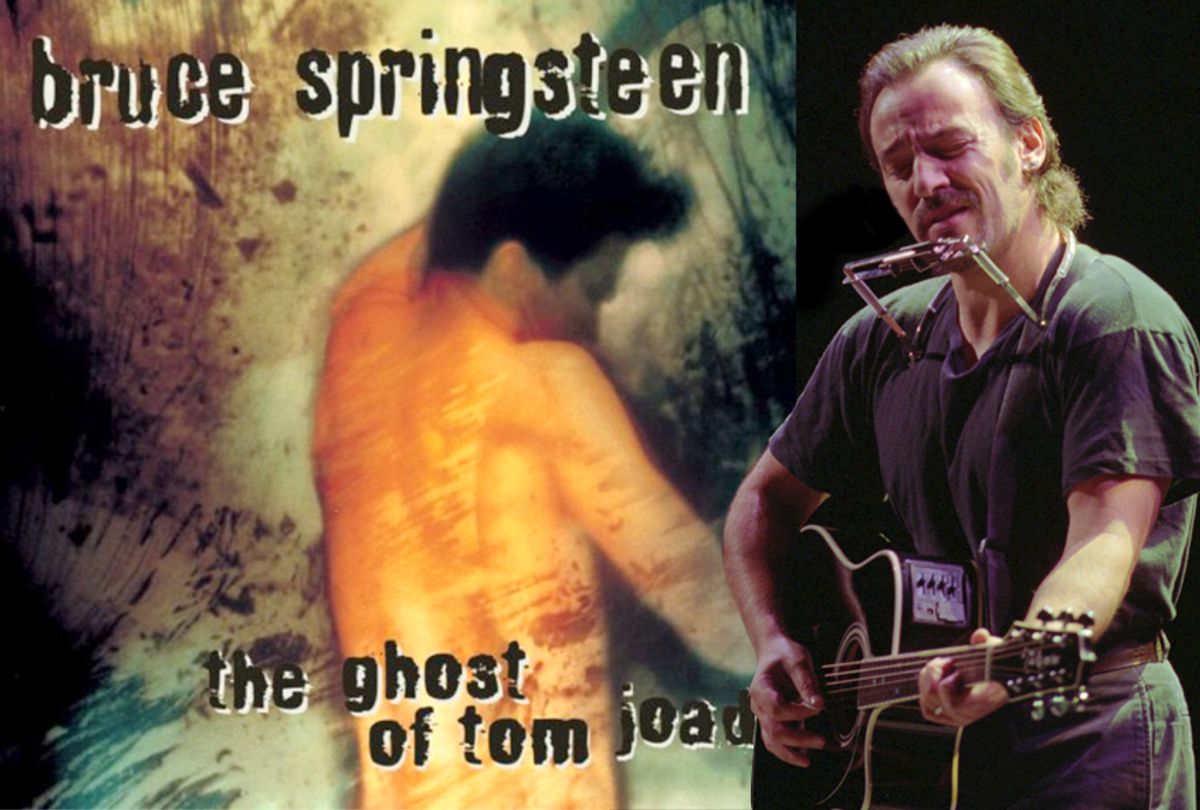

Heroes and corpses populate the songs of Springsteen’s 1995 record "The Ghost of Tom Joad." Released in the immediate aftermath of Springsteen’s success with the Oscar winning song “Streets of Philadelphia” and the popularity of his first Greatest Hits collection, Springsteen’s second folk album gave artistic life to the stories of depressed convicts, hopeful immigrants and homeless vagrants when illegal immigration was climbing toward a peak in American life. Twenty-two years later, illegal immigration is down to near historic lows, but given the Trump administration’s cruel assault on immigrants, and much of the electorate’s deranged support of it, Springsteen’s music emerges with a new power.

The September release from the live Springsteen archives of the Belfast performance of The Ghost of Tom Joad Tour is timely to the point of profound and eerie resonance.

“The poor, you will always have with you,” the Bible says, and for many people, the permanence of poverty provides justification for indifference to the suffering of the destitute. Apathy is especially common in America, where images of hunger and isolation give painful contradiction to “land of opportunity” pride and “city on a shining hill” myth.

"The Ghost of Tom Joad" was a brave record for Springsteen. It is a library-like quiet exploration of poverty in the world’s wealthiest nation. The verbosity of the lyrics, along with the minimalism of the music, makes the experience of listening to the record approximate to digesting a collection of short stories. Bruce Springsteen played most of the instruments on the record, but for several songs, he did have the backing of a small band — drums, bass, keyboards and violin.

An easy assumption to make is that the live presentation of the material, without any backup band, as Springsteen toured alone for the first time, would become even sleepier. As with the most rollicking of Springsteen anthems, the music manages to grow fully into life through live performance. By the strength of Springsteen’s vocals, the mastery of his guitar playing and the dynamism of his harmonica ornamentation, most of the songs actually pull of the magic trick of gaining in vitality, rather than losing momentum.

The sound quality of the live archival release is extraordinary. It feels as if Springsteen is sitting in your living room on an overcast evening, giving you a quiet tour of an America almost always kept undercover.

The show begins just as the record does, with the title track, “The Ghost of Tom Joad.” Springsteen sings of preachers sleeping underneath the bridge, lighting up butts of cigarettes scattered at their feet and praying for the moment “when the last shall be first and the first shall be last.” “Welcome to the new world order,” he announces with sardonic delivery, giving painful contrast to the phrase President George H.W. Bush used to predict a new era of peace and prosperity after the Cold War and the continuation of the destructive poverty present throughout, what Michael Harrington famously called, “the other America.”

An extensive paraphrase of Tom Joad’s “you’ll see me” speech, in John Steinbeck’s literary classic, and the John Ford film of the same name, closes the song. Joad becomes a specter who will haunt every scene and setting of injustice.

Now Tom said, “Mom, wherever there’s a cop beatin’ a guy

Wherever a hungry new born baby cries

Where there’s a fight ‘gainst the blood and hatred in the air

Look for me mom I’ll be there . . .

The song as show opener sketches the outline of a portrait to fully form throughout the performance. Springsteen depicts the depths of despair in search of some faint source of hope — what Walt Whitman called the “half lights of evening.” Unlike “Born to Run” or “Badlands,” Springsteen’s half lights become so slight on "The Ghost of Tom Joad" that they are nearly invisible. The entire shows ends with “The Promised Land” — an almost spooky rendition in which Springsteen bangs on his guitar like a drum and sings in a slow drawl, finally shouting in full voice to emphasize key phrases in the momentous last verse — “blow away the lies that leave you nothing but lost . . .”

In recent years with the E Street Band, Springsteen has taken to arranging setlists according to an almost arbitrary shuffle. The shows seem designed to illustrate his status as rock’s greatest live performer, giving colorful showcase to the dexterity and variety of his catalogue and his charismatic frontman personality.

The Ghost of Tom Joad Tour demonstrates Springsteen with a more urgent and intense mission. The song pairings in the setlist provide powerful opportunities to consider the ideas of his lyrics and the connections between his old and, at the time, new work. In the middle of the show, Springsteen informs the overseas audience that a group of homeless Vietnam veterans live in the California desert. He then plays a Tom Joad outtake, eventually released on the Tracks boxset, “Brothers Under the Bridge.” With barely a second of silence after the song’s final notes, Springsteen then starts banging out the blues on his guitar and singing a dark and bitter version of “Born in the U.S.A.”

The same blues is present on his fiery performance of “Murder Incorporated.” “When you deem people’s lives and dreams expendable,” Springsteen announces in his short introduction, “you got Murder Incorporated.” The song that follows is “Nebraska,” giving the protagonist’s indictment of the “meanness in the world” an entirely new, and even more frightening, resonance.

“We’re moving from murder to motherhood,” Springsteen then informs the audience. He finds the half lights – his love for his mother in “The Wish” and the tender pleasures of an unexpected night of carnal joy with a lover in “It’s The Little Things.”

Bruce Springsteen has an odd relationship with his massive audience. Many fans treat him with the devotion and admiration a cult leader would expect from his followers, while an even larger percentage views him as hardly any different from any other popular entertainer, expecting him to play every up tempo song from his Hits record and quietly protesting when he deviates from the plan, by leaving their seats. The long line out the door to the concession stands during a Springsteen show when he plays an obscure or slow song is as disrespectful as it is weird.

At the onset of the Belfast performance, Springsteen tells his crowd that he would appreciate their quiet during the music and that if anyone around them is talking, “just lean over and politely tell them to ‘shut the fuck up.’” He gave these instructions on a nightly basis throughout the tour, leading many die hard fans to christen it the “Shut the Fuck Up Tour.”

Silence is necessary for full appreciation of these songs. It is rare that Americans focus intently on art, even moreso now than in the 1990s, but the rewards of discipline and patience, even at a concert of a rock star, are immense. In his song about a man’s troubled thoughts over a love affair gone bad, “Dry Lightning,” Springsteen gives the description of the dawn as “the piss yellow sun comes bringing up the day.” The character is so bitter that a sunrise makes him think only of human waste. The next song, “Reason To Believe,” becomes an even more guttural cry of existential angst than it is on Nebraska. As Springsteen cries out in the opening verse about a man poking a dead dog with a stick, you get the feeling that, in the quiet, ghosts — good and evil — haunt this music.

To close the main set, Springsteen takes his listeners to the border towns of sadness along the Mexican-American scar. Springsteen tells a story about meeting a Mexican man on a motorcycle trip in the Southwest, who confided in him about the death of his brother. “His voice always stayed with me,” the songwriter confesses, before giving demonstration to how he creatively infused that voice in a story of his invention. “Sinaloa Cowboys” describes two Mexican brothers who move to America and decide to help cook methamphetamine after learning that they can make “half as much in one ten hour shift” as they can working a full year in the orchards. “For everything the North gives, it exacts a price in return,” their father warns them before they make the trek, and soon they measure that cost. One of the brothers kisses the other and buries him after a meth lab explosion.

It is a small crime that the “The Line” has not become a Hollywood film. Springsteen’s song tells the story of a man who, after his discharge from the Army in San Diego, takes a job with the border patrol. He becomes close friends with his partner, whose family is from Guadalajara — “So, the job is different for him.” The young border patrol officer instantly falls in love with a beautiful mother who they prevent from sneaking across and promises to help her get into America. She makes it, but he loses sight of her and spends the rest of his nights searching the bars in the migrant towns for “Luisa with the long black hair falling down.”

“Balboa Park” tells the story of teenage boys who make it to California, and with no means of earning an income, they sell drugs or their bodies. One of them gets hit by a car, and the song ends with him wounded on the pavement “listening to the cars rushing by so fast.” Springsteen introduces the song by celebrating the “window of grace” his children opened in his life and asking what happens when that grace becomes violated.

The stories of Springsteen’s songs shine a searchlight in the American night, exposing the underside of the American dream that most citizens would prefer not to acknowledge. Springsteen’s artistic compass protects him from veering off road into political lecture or producing op-eds put to music. These are human – all too human – stories in which the characters scream through the soft music.

In the encores, Springsteen tells the story of Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s. They settled in Texas as fishermen —“Galveston Bay,” as the song is called — and soon found themselves fighting against harassment, assault and torment from not only hostile locals, but also the Ku Klux Klan. “There was talk of America for Americans,” Springsteen sings. After the election of Donald Trump, that talk operates according to the euphemisms “economic nationalism” and “America First” but as the Texas story Springsteen sings so well makes clear, the history behind such loose and irresponsible rhetoric is hideous in its brutality.

“Oh, what are we without hope in our hearts?” Springsteen sings with tender voice in “Across the Border.” Each verse builds in drama as the dreams of its immigrant narrator become more beautiful. He goes from simply seeking shelter and stability to expressing faith in the common community of humanity. Springsteen sings in a falsetto to close the song, and the main set, that is luminous but also desperate. His voice could crack at any moment. It is as fragile as the lives of men crawling through the sand, risking death by thirst, and it is as frail as the porcelain hope for beloved union of disparate people.

America has made significant progress since Springsteen performed his songs of protest and pain in the mid-1990s, and it has also regressed in ways unpredictable and potentially catastrophic.

The best hope that Springsteen offers in his 1996 performance, and that he continues to project in the present, even if the $850 price tag on his Broadway shows is vomitous (“trust the art, not the artist,” he once told an interviewer), is the beauty and utility of art.

Tom Joad is a fictional character. The homeless drifters who populate “The Ghost of Tom Joad” wait on his spirit, not because of what he did or who he was — he did not even exist — but because of what he came to represent. Art presents the world of the imagination, a larger and better world than that which is tangible and terrestrial.

Whenever there is injustice and suffering, and wherever there is cruelty and misery, the artistic voice can emerge through the cacophony to amplify not only that which is worth hearing, but something worth believing.

Shares