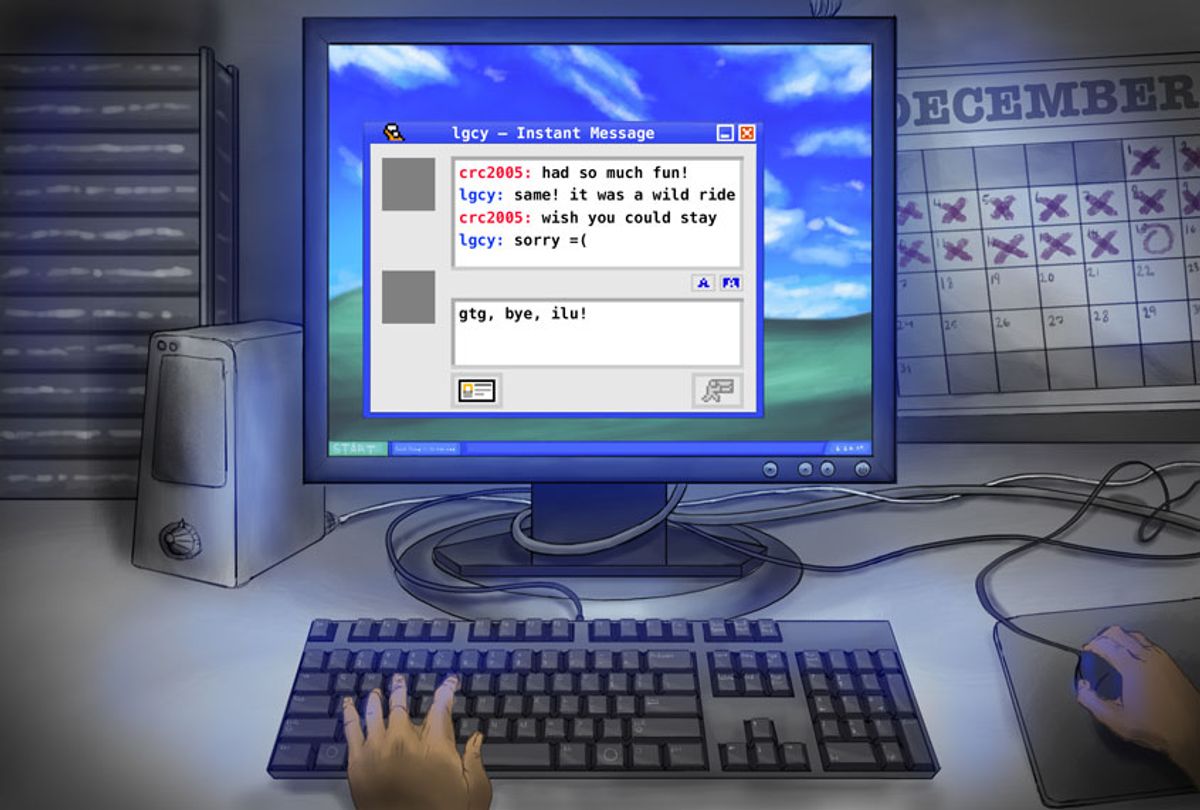

I’m in the dark family room, bouncing on my heels in the computer chair, leaning toward the monitor, slugging a can of Halfway to Heaven — the nickname the girls I’m IM-ing have for Diet Mountain Dew. My dad is on the couch, and I shrink the chat windows whenever I hear his knees creak. On TV, “Top Gun” plays on mute; by the mantle, the Airedale sleeps; the only sound in our house beside those knees is my fingers staccato on the keyboard.

“That’s all homework?” my dad asks during a commercial. “What are you doing, Jo?”

Jo? I think. Who’s Jo?

My first AIM username was Gucci60525 — my zip code plus a nod to “Spiceworld” (“Should I wear the little Gucci dress, the little Gucci dress, or the little Gucci Dress?”). When I outgrew Posh Spice, I slunk into Hollygolightly6985; with the release of “Man on the Moon,” I goofed into Kaufmaniac6985; when I’d memorized “American Beauty,” I snagged Spacey6985. My last username was pennylane6985: equal parts The Beatles and “Almost Famous.” By that time — I was a junior in high school — I’d traded the Halfway to Heaven for espresso and vanilla cloves.

* * *

The news arrived last week, as unwelcome as a chat invite from your best friend’s mom: AOL was shutting down AIM, its messaging service. Cue sign-off sound effect, the Internet responded, eulogizing the service that introduced the world to buddy lists, away messages, and profiles, with a pastiche of levity, longing and lovingly-excavated personal ephemera. The tributes are warranted. AIM paved the way for text messaging, Facebook, and beyond — all without (at least in the earliest years) profile pics. In “The Rise and Fall of AIM, the Breakthrough AOL Never Wanted,” Jason Abbruzzese reported that, at its peak, AIM drew “as many as 18 million simultaneous users.”

I learned from Abbruzzese that a subset of those users worked on Wall Street. This surprised me until I realized what young women like me, who were becoming teenagers at the end of the ’90s, had in common with those brokers: We too were trading futures and commodities, but on AIM the potential gains were our teenage selves.

What does it mean when a technology that shaped your identity dies? Who did we become as users of those technologies? And what does it mean now that our messaging is stitched to our phone numbers, our Facebook profiles, our flesh-blood-and-birthdate selves? Perhaps it’s easy to dismiss our AIM ancestry, merely a blip in the Intro to Social Media textbooks. Maybe it’s tempting to consider our emo away messages with bemusement (I’m looking at you, Wall Street), our screen names with a *head slap* — until you remember that all we had were away messages and usernames. I fear being so flip with the tools I — we — used to construct our most intimate identities.

I fell in love with two kinds of people on AIM: vaguely athletic nerd-boys and girls with eating disorders. My buddy list was filled out by others — the cool kids I knew in AP Art History, the runners who inside-out French-braided my hair before meets — but the anorexic girls I counted as my best friends and the boys I liked were the people I wanted to talk to, along with the “fishys,” a subset built out of the pro-recovery eating disorder website Something Fishy, women across the country whose lives, like mine at the time, were ruled by scales, laxatives and therapists.

Illness was one common tongue; sex was another. As a young woman, AIM helped me be fluent in both. It let a generation communicate in ways that would’ve been mortifying, sappy, or straight-up taboo in high school, that big top of real life.

* * *

In the summer of 1999, before I began ninth grade, I took a typing class. The instructor sidled behind the swivel chairs, watching our hands beneath cardboard boxes designed to hide the keyboard. You stuck your hands in like Audrey Hepburn tempting the oracle in “Roman Holiday”; you hoped you knew home row, had learned the raised dash on the letter J.

That class taught me to type fast, but AIM taught me to type faster. I had to keep up when MacRed451 called me “Babe.” (He was my best friend’s cousin, his screen name a result of the self-reported fact that he enjoyed “macking” on the ladies.) I liked how InchoatusMcGee sent passages from John Irving novels, and I liked responding with debased lines from the annals of Henry Miller. At the same time, ElleGirl40 might be telling me about the lock her parents affixed to the medicine cabinet. PurpleHaze203 would be sending pain-stoppering lyrics from the Black Crowes: sometimes, we took our correspondence offline, and she sent me long letters on paper licked with marijuana smoke and cotton candy perfume.

She didn’t sound so stressed about her eating disorder away from AIM. I noticed how, when I was depressed, I showered a lot in real life; on AIM, I tried to talk about it.

Depressed, starving, smart, bookworm, babe: I could be many versions of myself when I was IM-ing, and I could cultivate each one with the sort of care there wasn’t room for in high school. You didn’t have that freedom when you passed a note; there wasn’t the same thrill of anonymity over the phone. Real life was a rush, but AIM invited you to think on the fly. Wittiness, sarcasm and sagacity were rewarded. The banter reminded me of a game my brother and I used to play in the family room, when we were home alone: Don’t Touch the Ground.

You moved one piece of furniture to the next, watching normal things like couch arms and chair backs morph beneath you.

Words did that on AIM: they changed, grew potent, gathered a charge. Words that sounded dumb in real life could be sexy (like babe); words that would be hard to utter over the phone (like, I threw up my dinner) appeared in the chat window as though from another pair of hands. Words grew, too. When my friends and I began dating, we developed a color code so we could report on our sexual activities. Pink was kiss.

And words could stand in for things I’d never do or say in real life. ((hugs)), I’d type to the Fishys, even as I knew, if I ever were to meet any of them, I’d be terrified to crush them. “Tell me what it’s like to masturbate,” I’d ask the guy friends I knew liked moxie. I heard about vacuum cleaners, mirrors, shampoo bottles, feeling powerful and strange. Of course, nothing was going to happen as a result of these interactions — right? — but it felt like anything could.

* * *

It’s hard to shake the tastes you develop early. Even today, a message from a certain guy friend or a woman (always with an eating disorder) will leave me staring at my phone screen, heart pounding, wishing I could see if I’d made a shrouded cameo in their away message.

My friends and I saved our chats in a folder in our email. We printed them out and studied them at sleepovers like we were annotating “Lady Lazarus” or acting out “Cosmo Confessions.” Juicier than the messages we received from boys were the phrases that sprung from our keyboards, those impulse-cured expressions of our most ardent hearts.

It was good to be sardonic and sincere, flirty and vulnerable. It was good to feel that our identities were tied to our bodies when, on AIM, our bodies were invisible. The newness of this made even the frightening realities of being a young woman less perilous: Pink4Days700 told me how a guy fingered her on the catwalk stretching over the Stevenson toll way; another, SnowQueen14, flirted her way into a phone call with a 34-year-old man.

Of course, my parents detested it. Recently, I spoke with my mother, who confessed that she’d asked my father and my uncle to retrieve my messages from the hard drive of the family PC. The two of them — engineers both — failed. What would they have seen had they succeeded? A lot of ellipsis. A lot of swearing. Every color in the rainbow (plus black and gray). Song lyrics, novel quotes, admissions of love, lurf and luff.

When my mother told me about the snooping, my whole spine bristled, the way it would, 15 years ago, when I sensed my father stirring as I typed. I didn’t tell her that. She had been worried about me, she said, and I couldn’t blame her. Then her voice changed; I could tell she was as disappointed because she sighed. *Le sigh* my friends and I used to write on AIM. *Le sigh.* My mother sounded older, beat, the way I felt. “When you closed out of those windows, everything was gone.”

Shares