Monday was the deadline to register to vote in Alabama's special election for the U.S. Senate seat vacated by Jeff Sessions, who is now attorney general. While preliminary numbers of how many new voters have registered are not yet available, newly enacted criminal justice reform could play a key role in the outcome of this close race.

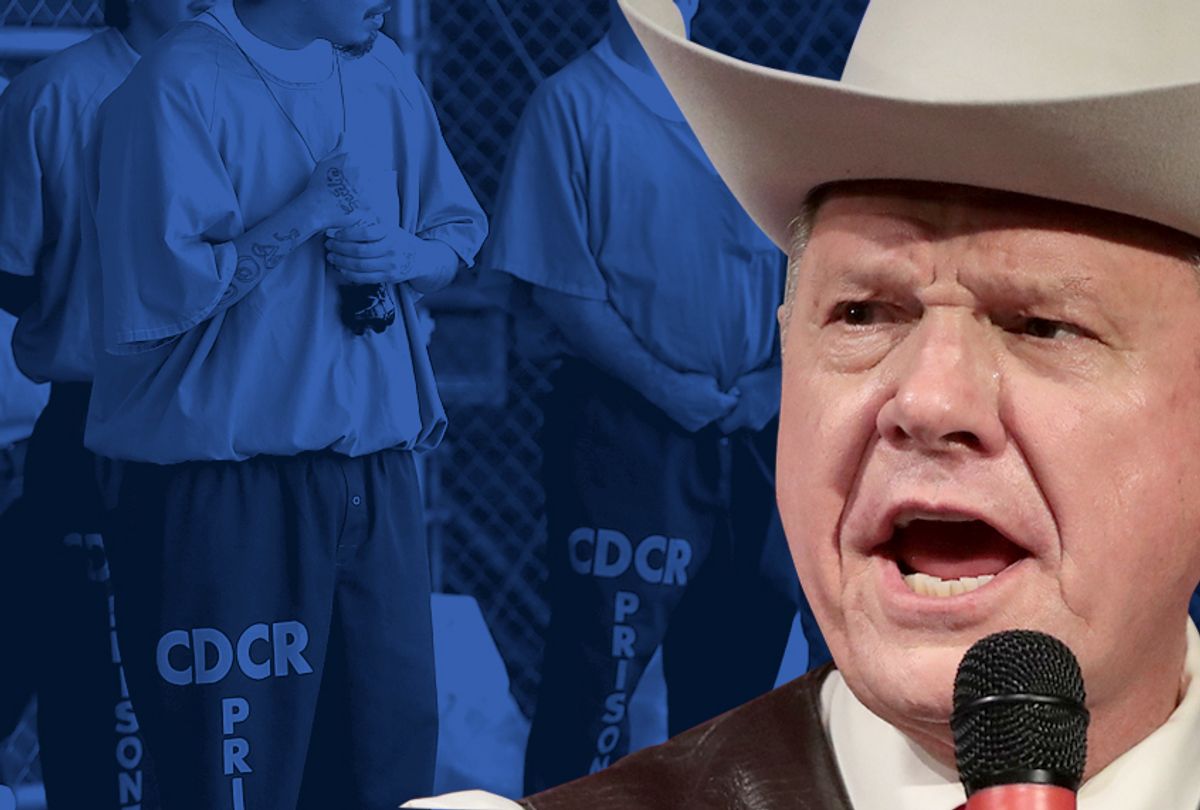

On Dec. 12, Alabama voters will decide between Democrat Doug Jones, a former U.S. attorney, and Republican Roy Moore, a controversial former judge who has been accused of numerous instances of sexual misconduct or predatory behavior with teenage girls.

Alabama is the “heart of Dixie,” one of the reddest states in the nation. It has not had a Democratic senator since Sen. Richard Shelby switched parties in 1994. Still, Roy Moore is beatable. The race is tight, according to nearly all available polling. President Donald Trump’s tiptoeing around endorsing a candidate his base adores has drawn additional scrutiny to what is already a race of national importance. The president has attacked Jones, who successfully prosecuted the terrorists who murdered four little girls in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, as “terrible on crime.”

With about as large a voting bloc of white evangelical Christians as anywhere in the country, the only realistic way for a Democrat to win in Alabama, even against a candidate as problematic as Moore, is through massive turnout from black voters. In an unexpectedly close contest, Moore’s poetic justice could potentially come via the very people he sent to prison as a doctrinaire judge.

For generations, the disenfranchisement of felons has resulted in tens of thousands of Alabamians, most of them black, being left out of the electoral process even after they have done their prison time and paid their debts to society. Anyone convicted of a “crime of moral turpitude” was prohibited from voting, but the state had never defined that ambiguous phrase. Under Alabama’s vague definition of a felony, individual registrars decided whether a given person could vote or not and, as a result, a disproportionate number of voters of color fell victim to the arbitrary disenfranchisement.

A law passed by the Republican legislature and signed this summer by Gov. Kay Ivey, a Republican and (somewhat reluctant) Moore supporter, has opened the doors for tens of thousands of Alabama citizens convicted of drug charges and other lower-level felonies to register to vote.

"To ensure that no one is wrongly excluded from the electoral franchise,” the legislation also restored voting rights for Alabamians who are charged with felonies but have not been convicted. Even those with a disqualifying conviction may still be able to restore their voting rights by applying for a Certificate of Eligibility to Register to Vote at a local probation and parole office. One obvious irony here is that Moore has been accused of what could plausibly be sex crimes — one of the remaining categories of felony that still disenfranchises Alabama citizens from voting.

There is a high probability that the number of individuals who have been convicted of felony drug crimes in Alabama is large enough to matter in such an election. There are about 50,000 people in jails and state prisons in Alabama and about 60,000 more on probation. Many elections, particularly special elections, can swing on a few thousand votes, or even less.

Virginia’s recent gubernatorial election is a good example.

As in Alabama, a Republican governor partially restored convicted felons' eligibility to vote in 2013. After, according to estimates from The Sentencing Project, 7.8 percent of voting-age Virginians were disenfranchised in 2016 because of their records — including more than one in every five African-Americans in the state — Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe further expanded voting rights to more than 150,000 people with felony convictions who had completed their sentences in August 2016. It seems likely that of the 168,000 people whose voting rights were restored, most who actually voted went for Democrats in a wave election that may have tipped control of the state legislature (pending recounts) and elected a Democratic governor by the widest margin in a generation.

Unlike Virginia, however, Alabama has done little to spread the word among former felons that they may be able to vote. But in Virginia, Oklahoma, Georgia and Maine, voters have mounted what has been dubbed a "red state revolt" in 2017 that might even take down a Republican in one of the reddest states in America. If Doug Jones is elected, Democrats could imperil Trump's tax bill as well as the rest of the GOP’s legislative agenda. That will surely put any bipartisan effort at federal criminal justice reform under increased scrutiny by conservatives who could point to its deleterious electoral effect on the Republican Party.

“We have the chance [in Alabama] to do the same thing they did in Virginia,” Kenneth Glasgow, founder of the Ordinary People Society, a nonprofit advocacy group that won a 2008 lawsuit to register people inside prisons — many of whom remained ineligible until this year — told ThinkProgress. “We can turn it blue. Well not blue, but we can add some color. Make it pink or purple.”

Shares