The great nocturnal invasion of American homes began at dusk on a Monday evening in October 1966 along the East Coast and spread inexorably westward during the next three hours. For the 187 million Americans living in the United States, the invasion centered around strange creatures almost universally smaller than an average adult human being. These miniature creatures dressed in bizarre clothing depicting other times, other places, even other dimensions. Miniature females sought entry into homes dressed as pint-sized versions of America’s favorite women with supernatural powers—Samantha Stevens of "Bewitched," or, as the companion/servant/nightmare of an American astronaut, a being from a bottle known as “Jeannie,” played by Barbara Eden. Diminutive male invaders often wore the green face of bumbling giant Herman Munster or the pointed ears of the science officer of the USS Enterprise, Mr. Spock. These miniature invaders were sometimes accompanied by still youthful but taller adolescents who may or may not have worn costumes as they chaperoned their younger siblings but invariably seemed to be holding a small box equipped with earplugs that allowed these teens to remain connected to the soundtrack of their lives, the “Boss Jocks” or “Hot 100” or “Music Explosion” radio programs.

These teenagers were different forms of invaders in the adult world of late 1966, as they seemed semipermanently attached to their transistor radios, spending four, six, or even eight hours a day listening to rapid-fire disc jockeys who introduced, commented upon, and played current hits such as “Last Train to Clarksville” by the Monkees, “96 Tears” by ? and the Mysterians, “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?” by the Rolling Stones, and “Reach Out I’ll Be There” by the Four Tops.

As the miniature “home invaders” were often invited by their “victims” into their living rooms to receive their candy “payoffs,” they encountered adults watching "The Lucy Show," "Gilligan’s Island," "The Monkees" and I Dream of Jeannie. The fact that nearly half of Americans in 1966 were either children or teenagers made it extremely likely that at least one or possibly even two of the programs airing on the three major networks would feature plotlines attractive to youthful viewers.

The most famous home that received the costumed “invaders” was 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Three years earlier that address had featured two young children as its residents, but the current residents were now looking forward to becoming first-time grandparents after the recent wedding of their daughter. While Lady Bird Johnson welcomed the diminutive visitors who passed through far more security than average homes, President Lyndon Baines Johnson was recovering from the massive jet lag and exhaustion incurred during a recent 10,000-mile odyssey across the Pacific Ocean.

A few days before Halloween, Lyndon Johnson had become the first president since Franklin Roosevelt to visit an active battle zone by traveling to a war-torn South Vietnam. While a quarter century earlier Roosevelt had been ensconced in the intrigue-laden but relatively secure conference venue of Casablanca, Johnson’s Air Force One had engaged in a rapid descent toward Cam Ranh Bay in order to minimize the time the president could be exposed to possible Viet Cong ground fire.

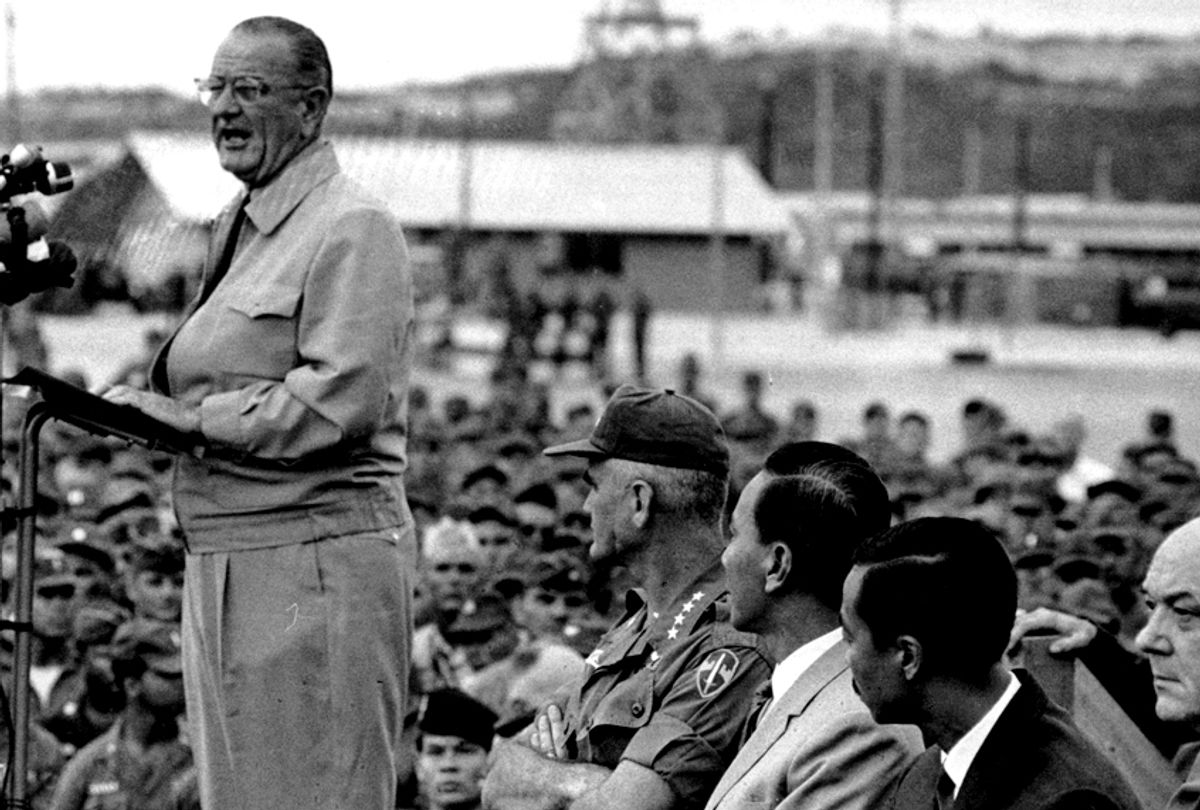

Johnson, dressed in his action-oriented “ranch/country” attire of tan slacks and a matching field jacket embossed with the gold seal of the American presidency, emerged from the plane with the demeanor of a man seeking to test his mettle in a saloon gunfight. Standing in the rear of an open Jeep, the president clutched a handrail and received the cheers of seven thousand servicemen and the rattle of musketry down a line of a nine-hundred-man honor guard. Meanwhile, a military band played “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” Johnson’s speech—considered by many observers to have been his best effort in three years in office—compared the sweating suntanned men in olive drab fatigues to their predecessors at Valley Forge, Gettysburg, Iwo Jima, and Pusan. He insisted that they would be remembered long after by “a grateful public of a grateful nation.”

Now, at Halloween, Johnson had returned to the White House, more determined than ever to (in his sometimes outlandish “frontier speak” vocabulary) “nail the coonskin to the wall” in concert with a relatively small but enthusiastic circle of allies, including Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand. All were dedicated to thwarting a Communist takeover of South Vietnam and possibly much of Southeast Asia. While European allies had decided to sit out this conflict, Johnson had been able to forge an alliance in which young men from Melbourne, Seoul, and Manila were joining American youths from Philadelphia to San Diego in a bid to prevent North Vietnam and its Viet Cong allies from forcibly annexing a legitimate but often badly flawed South Vietnamese entity.

Unlike Halloween of 1942, when even the youngest trick-or-treaters had some semblance of knowledge that their nation was involved in a massive conflict that even affected which toys they could buy, what was for dinner, or whether they would have the gasoline to visit their grandparents, the United States in October 1966 displayed little evidence that a war was on. Neighborhood windows did not display blue or gold stars signifying war service. Dairy Queen stands did not run out of ice cream due to a sugar shortage, McDonald’s restaurants were in the process of offering even larger hamburgers than their initial 15-cent versions, and there were no contemporary cartoon equivalents of the Nazi-Japanese stereotypes in the old Popeye and Disney cartoons. In October of 1966, “The War” still primarily referenced the global conflict of a generation earlier. Names such as Tet, Hue, My Lai, and Khe San were still obscure words referenced only as geographical or cultural terms by a minority of young soldiers “in the country” in South Vietnam.

Halloween 1966 was in many respects a symbolic initiation of the long 1967 that my new book, "1967," will chronicle. Post-World War II American culture had gradually chipped away the edges of the traditional January 1 to December 31 annual calendar. Nearly sixty million American students and several million teachers had begun the 1967 school year in September as they returned to classes in a new grade. The burgeoning television industry had essentially adopted the same calendar, as summer reruns ended soon after children returned to school, so that the 1967 viewing season began several months before New Year’s Day. Car manufacturers began discounting their 1966 models in the autumn as new 1967 autos reached the showroom far ahead of calendar changes. While the college basketball season did not begin until December, about three weeks later than its twenty-first-century counterpart, the campaigns for the National Hockey League 1967 Stanley Cup and the corresponding National Basketball Association Championship title began far closer to Halloween than New Year’s Day. This reasonable parameter for a chronicle of 1967 would seem to extend roughly from late October of 1966 to the beginning of the iconic Tet Offensive in Vietnam during the last hours of January 1968.

While the undeclared conflict in Vietnam had not yet replaced World War II as the war in many Americans’ conscious thought, no sooner had the president returned from Southeast Asia than a new threat to Johnson’s presidency emerged. Since his emergence as chief executive in the wake of the Kennedy assassination three years earlier, Johnson had driven a balky but Democratic-dominant Congress to one of the most significant periods of legislation activity in the nation’s history. Bills enacting civil rights legislation, aid to schools, public housing subsidies, highway construction, space exploration, and numerous other projects wended their way through Congress, often in the wake of the president’s controversial treatment of uncommitted lawmakers through a combination of promises and goadings. By the autumn of 1966, supporters and opponents of the Johnson’s Great Society began to believe that, for better or worse, the president was beginning to envision a semipermanent social and political revolution in which current laws would be substantially enhanced while new reforms xvi prologue autumn were proposed and enacted. However, a week after Halloween, this prospect collided with a newly emerging political reality.

The Goldwater-Johnson presidential contest two years earlier had not only resulted in the trouncing of the Arizona senator, but essentially provided the Democrats with a two to one majority in both houses of Congress. While some northern Republican lawmakers were more politically and socially liberal than a number of Southern Democrats, party discipline still obligated these southern politicians to support their leader. At least in some cases, the Great Society legislation kept churning out of the Congress, notably with the startling 100 to 0 Senate vote for the 1965 Higher Education Act. Now, as Americans voted in the 1966 elections, the seemingly semi-moribund GOP came back dramatically from its near-death experience.

When the final votes were tallied, the Republicans had gained eleven governorships that added to the fifteen they already held, which now meant that the majority of states were led by a GOP chief executive. The relatively modest party gain of three Senate seats was overshadowed by a spectacular increase of forty-seven seats in the House of Representatives, which more than repaired the damage of the 1964 fiasco. Newspapers and news magazines featured stories purporting that “the GOP wears a bright new look.” Politics in ’66 sparkled the political horizon with fresh-minted faces, and the 1966 election has made the GOP presidential nomination a prize suddenly worth seeking. The cover of Newsweek displayed “The New Galaxy of the GOP” as “stars” that “might indeed beat LBJ in 1968.”

This cover story featured George Romney, “the earnest moderate from Michigan”; Ronald Reagan, “the cinegenic conservative from California”; and other rising stars of the party. Edward Brooke, the first African American US senator since Reconstruction, “Hollywood handsome” Charles Percy from Illinois, Mark Hatfield of Oregon, and even the newly energized governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, were all mentioned. Notably absent from this cover story “galaxy” was the man who easily could have been in the White House in autumn 1966, Richard M. Nixon. According to the news media, the former vice president’s star seemed to be shooting in multiple directions. One article dismissed him as “a “consummate” old pro “who didn’t win anything last week and hasn’t won on his own since 1950,” while another opinion held that the Californian had emerged as “the party’s chief national strategist” as he urged the formula of running against LBJ and in turn most accurately predicted the results.

All around the nation, analysis of the 1966 election supplied evidence that the Democratic landslide of two years earlier was now becoming a distant memory. Only three Republican national incumbents running for reelection lost their races across the entire nation. Republicans now held the governorships of five of the seven most populated states. Romney and Rockefeller had secured 34 percent of the African American vote in their contests, and Brooke garnered 86 percent of the minority vote in his race.

While the GOP had lost 529 state legislature seats in the legislative fiasco of 1964, they had now gained 700 seats, and a Washington society matron described the class of new Republican legislators as “all so pretty” due to their chiseled good looks and sartorial neatness—“there is not a rumpled one in the bunch.” Good health, good looks, and apparent vigor seemed to radiate from the emerging leaders of the class of 1966.

George Romney, newly elected governor of Michigan, combined his Mormon aversion to tobacco and spirits with a brisk walk before breakfast to produce governmental criticism of the Vietnam War that caught national attention. His Illinois colleague, Senator Charles Percy, was described as a “Horatio Alger” individual, a self-made millionaire with the “moral fibers of a storybook character.” The equally photogenic Ronald Reagan looked a good decade younger than his birth certificate attested, and alternated stints in his government office with horseback riding and marathon wood-chopping sessions. All of these men were beginning to view 1967 as the springboard for a possible run at the White House, especially as the current resident of that dwelling seemed to be veering between a brittle optimism and a deep-seated fear that the war in Southeast Asia was about to unravel the accomplishments of his Great Society.

While the new galaxy of emerging Republican stars was reaping widespread public attention after the election of 1966, two men who had come closer to actually touching the stars were gaining their own share of magazine covers and media attention.

James Lovell and Buzz Aldrin spent part of late 1966 putting exclamation points on Project Gemini, the last phase of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s plan to fulfill John F. Kennedy’s challenge to land Americans on the moon before the 1960s ended. One of the iconic photos of late 1966 occurred when Lovell snapped a photo of Aldrin standing in the open doorway of their Gemini spacecraft, with the Earth looming in the background. James Lovell Jr. and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin were marking the end of the run-up to the moon that had been marked by the Mercury and Gemini projects and which were now giving way to the Apollo series, which would eventually see men setting foot on the moon.

Journalists in late 1966 chronicled the sixteen astronauts who traveled eighteen million miles in Earth orbits as participants of “Project Ho-Hum,” or engaged in clocking millions of miles with nothing more serious than a bruised elbow.”

Life columnist Loudon Wainwright compared the almost businesslike attitude of both the astronauts and the American public in 1966 to six years earlier, when citizens waited anxiously for news of a chimpanzee who had been fired 414 miles out into the Atlantic. They admired its spunk on such a dangerous trip, then prayed for Mercury astronauts who endured the life-and-death drama of fuel running low, hatches not opening properly, and flaming reentries that seemed only inches from disaster. Now, in 1966, James Lovell, who had experienced eighty-five times more hours in space than John Glenn a half decade earlier, could walk down the street virtually unnoticed. By late 1966, American astronauts seemed to be experiencing what one magazine insisted was “the safest form of travel,” but only days into the new year of 1967 the relative immunity of American astronauts would end in flames and controversy in the shocking inauguration of Project Apollo.

Late 1966 America, to which Lyndon Johnson returned from Vietnam and James Lovell and Buzz Aldrin returned from space, was a society essentially transitioning from the mid-1960s to the late 1960s in a decade that divides, more neatly than most, into three relatively distinct thirds. The first third of this tumultuous decade extended roughly from the introduction of the 1960 car models and the television season in September of 1959 and ended, essentially, over the November weekend in 1963 when John F. Kennedy was assassinated and buried.

This period was in many respects a transition from the most iconic elements of fifties culture to a very different sixties society that did not fully emerge until 1964. For example, the new 1960 model automobiles were notable by their absence of the huge tail fins of the late 1950s, but were still generally large, powerful vehicles advertised for engine size rather than fuel economy. Teen fashion in the early sixties morphed quickly from the black leather jacket/poodle skirts of Grease fame to crew cuts, bouffant hairdos, penny loafers, and madras skirts and dresses. Yet the film "Bye Bye Birdie," a huge hit in the summer of 1963, combined a very early sixties fashion style for the teens of Sweet Apple, Ohio, with a very fifties leather jacketed and pompadoured Conrad Birdie in their midst.

Only months after "Bye Bye Birdie" entered film archives, the mid-sixties arrived when the Beatles first set foot in the newly named John F. Kennedy airport in New York, only a few weeks after the tragedy in Dallas. As the Beatles rehearsed for the first of three Sunday night appearances on "The Ed Sullivan Show," boys consciously traded crew cuts for mop-head styles and teen girls avidly copied the styles of London’s Carnaby Street fashion centers. By summer of 1964, "A Hard Day’s Night" had eclipsed Birdie in ticket sales and media attention.

While the early sixties were dominated by the splendor and grandeur of the Kennedy White House, the wit and humor of the president, the effortless style of Jacqueline Kennedy, and the vigor of a White House of small children, touch football, and long hikes, the mid-sixties political scene produced far less glamour in the nation’s capital. Ironically, Lyndon Johnson was far more successful in moving iconic legislation through a formerly balky Congress, yet the Great Society was more realistic but less glamorous than the earlier New Frontier. While the elegantly dressed Jack and stunningly attired Jackie floated through a sea of admiring luminaries at White House receptions, Johnson lifted his shirt to display recent surgery scars and accosted guests to glean legislative votes while the first lady did her best to pretend that her husband’s antics had not really happened.

Much of what made mid-sixties society and culture fascinating and important happened well outside the confines of the national capital. Brave citizens of diverse cultures and races braved fire hoses and attack dogs in Selma, Alabama, to test the reach of the Great Society’s emphasis on legal equality, while television networks edged toward integrating prime-time entertainment. Those same networks refought World War II with "Combat," "The Gallant Man," "McHale’s Navy," and "Broadside." James Bond exploded onto the big screen with "From Russia With Love," "Goldfinger," and "Thunderball," and the spy genre arrived on network television with "The Man from U.N.C.L.E.," "Get Smart," and even "Wild, Wild West."

The mid-sixties soundtrack rocked with the sounds of Liverpool and London as the Beatles were reinforced by the Rolling Stones, the Zombies, the Kinks, the Troggs, and the Dave Clark Five. American pop music responded with Bob Dylan going electric with “Like a Rolling Stone” and the Beach Boys’ dreamy "Pet Sounds." Barry McGuire rasped out the end of civilization in “Eve of Destruction,” while the Lovin’ Spoonful posed a more amenable parallel universe with “Do You Believe in Magic?”

The American sports universe of the mid-1960s produced a number of surprising outcomes that would significantly influence competitions in 1967 and beyond. For example, the 1964 Major League Baseball season featured a National League race dominated for all but the final week by one of its historically most inept teams. After the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies “Whiz Kids” soared to a league title, and a four-game sweep loss to the New York Yankees, the franchise spent most of the next decade mired in the National League cellar. Then a good but not exceptional team roared out to a spectacular start and, by mid-September, was printing World Series tickets with a seven-game lead with twelve games remaining. Then the Phillies hit a ten-game losing streak that included two losses when an opposing player stole home in the last inning. Meanwhile, the St. Louis Cardinals, who played badly enough to convince their owner to threaten to fire their manager at the end of the season, went on a winning streak, overtook the Phillies to win the pennant, then beat the New York Yankees of Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, and Yogi Berra in a dramatic seven-game set.

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, a relatively stern-looking coach old enough to be the grandfather of his players was assembling a team that would carry UCLA to NCAA basketball championships in 1964 and 1965, virtually never losing a game in the process. Then, in the spring of 1965, coach John Wooden received news that the most highly sought-after high school player in the country, Lew Alcindor of Power Memorial High School in New York City, was leaving the East Coast to join the UCLA Bruins as a member of the freshman team. That team ended up winning the 1967 NCAA championship and became the final piece in one of the greatest collegiate basketball teams in history.

Finally, during this middle sixties period, Joe Namath a brash, unpolished quarterback from Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, turned his back on northeastern colleges and enrolled at the University of Alabama. His subsequent sensational but controversial college career with the Crimson Tide would lead to victories in premier bowl games and his status as the most prized draft pick for the rival National and American football leagues. His acceptance of one of the largest signing bonuses in history — to join the New York Jets of the upstart AFL — would set in motion a series of negotiations that would shock the football world. In the summer of 1966, the rival leagues announced a merger that would culminate with an AFL-NFL championship game, quickly designated as the “Super Bowl.” The first such game would be played January 1967.

While all this was going on, a very real war was raging in Southeast Asia. The fifteen thousand largely advisory American troops in place in South Vietnam in 1963 had, by late 1966, risen toward the half-million mark. Death totals were rising regularly at the time of Lyndon Johnson’s dramatic appearance at Cam Ranh Bay.

By Halloween of 1966, American forces had been engaged in extensive combat in Vietnam for almost a year. Twelve months earlier, a massive Communist offensive intended to slice South Vietnam in two was initially thwarted by elements of the American Air Cavalry at the bloody battle of Ia Drang Valley. Though the enemy drive was blunted, the American death toll leaped from dozens to hundreds within a few days. Interest in the war from both supporters and opponents began rising rapidly, as television networks committed more time and resources to coverage of the conflict as well as pro-war and anti-war demonstrations that were taking place across the nation. By the end of 1966, the Vietnam War was the major American foreign policy issue, and it would grow even larger during the next twelve months. The question that still remained in late 1966 was how the conflict in Southeast Asia would affect an economic expansion that had created increasing prosperity through the entire decade of the 1960s.

As Americans prepared to celebrate the beginning of what promised to be an eventful new year, the news media was filled with summaries of society in 1966 and predictions for the future. The closing weeks of the year had produced a continuing economic surge that had pushed the Dow Jones Industrial Average past the 800 mark. Unemployment was hovering in a generally acceptable 3.5 percent range, with a feeling that there were more jobs than applicants for most positions requiring a high school diploma or above. The $550 billion Gross National Product of 1960 had climbed to $770 billion. Fortune magazine noted that “the great industrial boom of the last six years has lifted factory output by 50 percent and total output by 33 percent.”

A frequent topic for journalists in late 1966 was the impact of an extended period of prosperity on the family and social life of an America now more than two decades removed from the challenges of war and depression. For example, twenty-five years after Pearl Harbor, the often uncomfortable reality of shared housing among extended family or even strangers — imposed by the Great Depression and then World War II — was almost totally absent in modern America. In fact, almost 98 percent of married couples now lived in their own household. The low marriage rate of the 1930s had rebounded to a 90 percent marriage rate among modern Americans. There was a nearly 70 percent remarriage rate among divorced citizens. Among the 25 percent of married Americans who had gotten divorced, about 90 percent now reported marital success the second time around.

The overwhelming tendency among young Americans to get married had been a key element in the iconic “baby boom” that had been a central element of family life for twenty years. Although the birth rate was just beginning to slip, the four-child household was basically the norm in contemporary society. Yet in this generally prosperous family environment, sociologists reported two problem areas: many children did not seem to have a concept of “what daddy did” in an increasingly office-oriented workforce, and in turn were less than enthused when “mommy sometimes worked too.” This was a situation quite different from the overwhelming “reality” on television comedies based on “typical” families.

All in all, 1967 already was beginning to look like a roller-coaster ride for more than a few Americans.

Shares