I've been around long enough to have gone through several presidential scandals. If there's one consistent theme among all of them, it's that there's always a moment when the president's defenders start to argue that even if the president did what he's accused of doing, it's not illegal and therefore it's no big deal.

During the Watergate scandal, Richard Nixon himself operated on the belief that his status as the chief executive meant that he answered to no authority. He fought the charges on that premise, until it became untenable when the Supreme Court ordered him to turn over the White House tapes and he lost the confidence of his own party, which told him it was time to go. After leaving office, he famously told interviewer David Frost, "When the president does it, that means it is not illegal."

In the Iran-Contra scandal, the argument was made explicitly by congressional Republicans, who fought the independent counsel investigation every step of the way. In the face of outright lying and obstruction of justice by Reagan administration officials, they waved it away as the result of excessive patriotism. Rep. Henry Hyde, an Illinois Republican, argued they deserved no punishment:

All of us at some time confront conflicts between rights and duties, between choices that are evil and less evil, and one hardly exhausts moral imagination by labeling every untruth and every deception an outrage.

During the Lewinsky scandal a decade later, Hyde was not quite so philosophical. While Bill Clinton's defenders all claimed that the alleged perjury and obstruction of justice by the president in dealing with his extramarital affair did not meet the impeachment threshold for a high crime or misdemeanor, Hyde thundered, "Lying poisons justice. If we are to defend justice and the rule of law, lying must have consequences."

In other words, these scandals are always partisan to some degree, which is to be expected. But they also always seem to feature arcane legal and constitutional arguments about what constitutes obstruction of justice and perjury as the scandal moves closer to the president himself.

Despite the fact that President Donald Trump hasn't even been in office a year, we have already reached the point where these questions are being asked. Cable TV lawyers are hashing out the usefulness of an archaic law like the Logan Act and arguing about whether lying to the FBI is a crime if it's not "material" or whether the president can be charged with obstruction of justice as a criminal matter.

Normally we don't reach this point so quickly, but then, Trump's administration is a dumpster fire in which two of his former top advisers have already been indicted and face jail time and there's more turnover in the White House than the average fast food joint. Mostly, however, the pace of this scandal's unfolding is a testament to the seriousness of the underlying issue: a foreign government sought to influence the U.S. presidential election to help its chosen candidate. It may be the most serious presidential scandal in our history.

It's certainly not the first time a nation has either openly or covertly interfered in another country's election to help one candidate or another. The United States has done it in the past, on multiple occasions. In this case, however, the point seems to have been to create discord and mistrust in the electoral system itself, to help Donald Trump malign and discredit his opponent and to turn allies against each other. This too is not unprecedented. Richard Nixon was known for this sort of thing -- they called it "ratf***ing," and one of Nixon's original hitmen, Roger Stone, was intimately involved in this one too. But the fact that it happened, and resulted in the election of someone so unqualified, has shaken the American democratic system to its core.

It's obvious at this point that there was a concerted Russian effort to infiltrate the Trump campaign. The extent to which it was successful is still unclear, although we have plenty of evidence that members of the Trump campaign were willing to talk about it. At least one, former campaign manager Paul Manafort, may well have been working for more than one boss. There are many questions about Trump's business dealings with Russia, mostly because he has been opaque and secretive about his finances and because the world in which he worked is rife with oligarchs and mobsters looking for people with whom to park their money. All this is worthy of a thorough investigation, particularly since Trump is so obviously unwilling to be forthcoming about any of it.

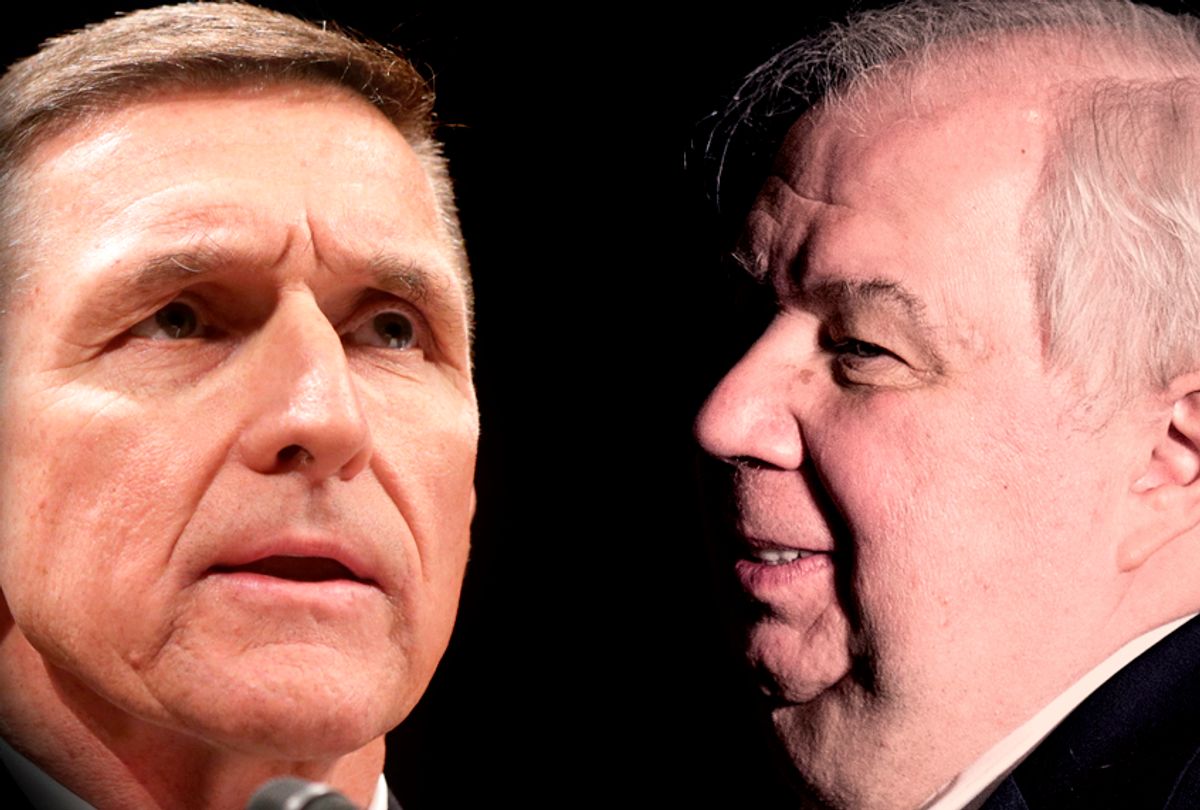

But frankly, even if none of that turns out to be true -- or if the Mueller investigation finds no evidence that anyone else committed any crimes -- it doesn't much matter. Michael Flynn has admitted to calling up Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak -- at the behest of other members of the incoming administration and likely the president himself -- and telling him not to worry about any U.S. retaliation against Russia for its election meddling, because when the Trump team took office they'd make it all go away. He might as well have said, "Tell Vlad thanks for the help. We've got his back."

Indeed, Donald Trump, who was then the president-elect, tweeted this the very next day:

What Flynn relayed to Kislyak that day was a shocking act of betrayal by the president-elect of the United States and his team. One can only imagine what authorities at the Department of Justice thought when they figured it out. After all, the Obama administration was not protesting the legitimacy of Trump's victory when it imposed those punishments. Our government was sending a straightforward message to the Russians that there would be a price to pay for their audacious interference in the American democratic system and their attack on American sovereignty. And then the newly elected president, the beneficiary of that attack, secretly sent a different message saying he would make sure there was no such penalty.

Was that to pay back Russia for its help or simply because he didn't want to give his political opponents any credibility? I can't say. But before he was even sworn in, Trump acted against the interest of the country in order to protect himself. Everything he's done since then has been in service of that same interest: Donald J. Trump.

Shares