We need to go back to the beginning, when the Dead were still known as the Warlocks, an electric blues band unlike most electric blues bands. Their first gig happened on May 5, 1965, at a pizza parlor in Menlo Park, California, the next town over from Palo Alto on the peninsula south of San Francisco that separates the San Francisco Bay from the Pacific Ocean. That summer, they landed a residency more like a prison sentence, playing five 50-minute sets six nights a week at the In Room in Belmont, “a heavy-hitting divorcee’s pickup joint” (McNally, 2002). It was a formative period. The band would hang around together all day, some of them often high on LSD, arrive at the club, smoke pot, and play for a few hours. The songs became louder, longer, and weirder the later it got. It was how they began to learn to play together, and this led to people showing up not to get lucky at the In Room, but to hear a band making music fusing elements of Junior Walker, John Coltrane, and even the passing trains that regularly rattled the bar—“as the band grew more and more attuned to the schedule, they learned to play with, instead of against, the sound.” By November, their reputation had extended beyond the Peninsula, sharing similar musical and ideological freedoms with other Bay Area bands, like the Charlatans, the Great Society, Quicksilver Messenger, and Jefferson Airplane.

That November, the Warlocks learned of another band called the Warlocks. In fact, there were two bands using the same name at that time. The Velvet Underground were known as the Warlocks in their early days, and there was also a garage band out of Dallas, Texas, that used the same moniker (and happened to include Dusty Hill who would go on to be a member of ZZ Top). High on DMT at Phil Lesh’s house on High Street in Palo Alto, Jerry Garcia discovered the term “grateful dead” in a 1956 edition of Funk and Wagnall’s "New Practical Standard Dictionary." These two seemingly incompatible words refer to a folktale about a corpse being refused a proper burial because of a debt owed. The tale’s hero unselfishly pays the debt, permitting the corpse’s spirit to be released from the dead body; later, the hero then encounters, and is rewarded by, the spirit he helped. As Dennis McNally writes: “The motif is found in almost every culture since the ancient Egyptians. Unknowingly, the Warlocks had plunked themselves into a universal cultural thread woven into the matrix of all human experience.”

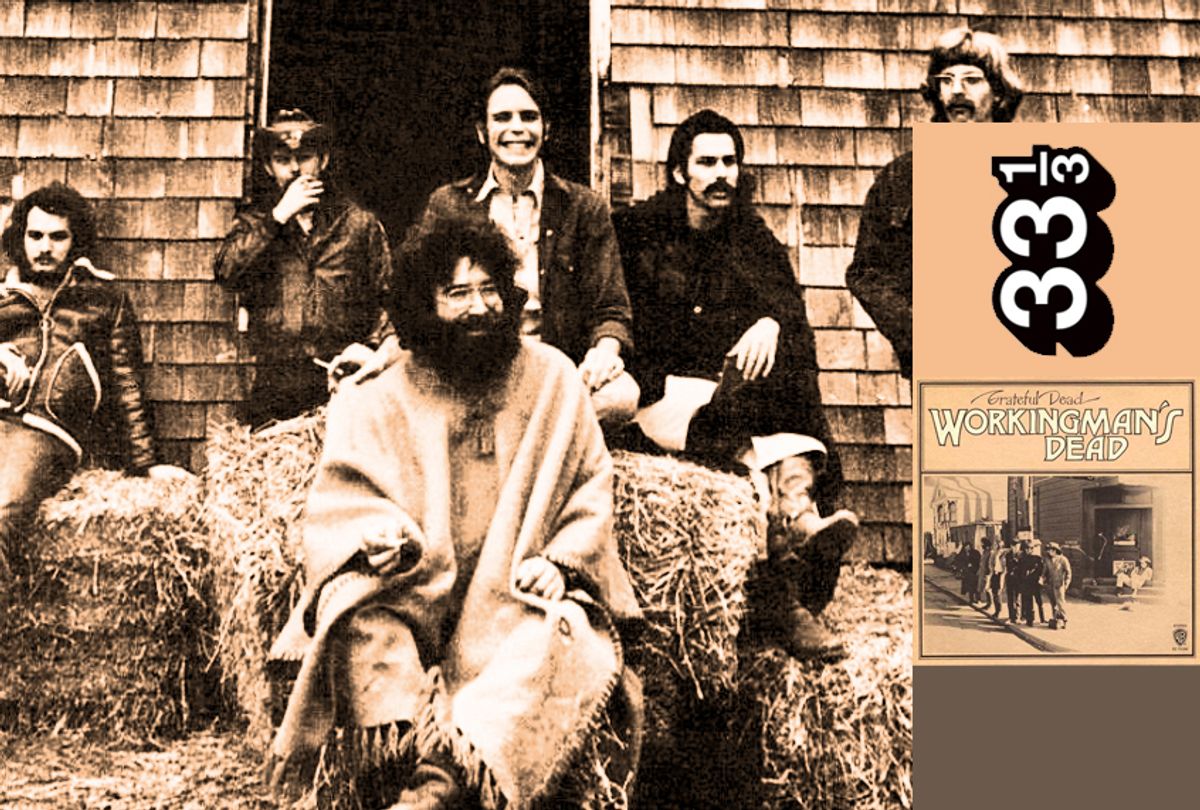

Garcia and Lesh had been experimenting with LSD before the formation of the Warlocks, but between the advent of the Dead and the recording of "Workingman’s Dead" the band had earned their reputation as psychedelic trailblazers during the Acid Tests, the LSD- and lightshow-drenched gatherings devised by Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test." The Dead, like the Pranksters, were born out of the 50s bohemian scene in and around Palo Alto. Kesey had showed up from Oregon to attend Stanford University in 1958 and found himself living on Perry Lane, “Stanford’s bohemian quarter . . . It was a cluster of two-room cottages with weathery wood shingles in an oak forest, only not just amid trees and greenery, but amid vines, honeysuckle tendrils . . . Everybody sat around shaking their heads over America’s tailfin, housing-development civilization.” With his country boy genuineness Kesey made his presence known right away on Perry Lane. His reputation boomed, however, after he volunteered for drug experiments conducted by Stanford scientists at the Veterans Hospital in Menlo Park. All sorts of drugs were administered to him, but it was the LSD that changed everything—“suddenly he was in a realm of consciousness he had never dreamed of before and it was not a dream or delirium but part of his awareness.” Kesey wanted to share this profound awareness with anyone brave enough to try so he started bringing the experimental drugs home to Perry Lane. He’d make LSD-laced venison stew and local artists and musicians, including Garcia, would come on over to get hip to new realms of awareness.

The founding members of the Dead – Garcia and Bob Weir on guitars and vocals; Phil Lesh on bass and occasional vocals; Bill Kreutzmann behind the drums; Ron “Pigpen” McKernan striding back and forth between an organ and a front-and-center microphone into which he sang and played harmonica – had met through the overlapping scenes on the Peninsula. They’d been running into one another starting as far back as the early 60s. Near the end of 1963 a developer’s vision of modernity brought the high times on Perry Lane to an end. Kesey, having made a name for himself as a prominent novelist with "One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest" and "Sometimes a Great Notion," moved up into the hills of La Honda, where he bought a “log house, a mountain creek, a little wooden bridge . . . a redwood forest for a yard.” By 1964, Kesey and the Pranksters were throwing weekly Saturday night parties during which most everyone ate acid and then ran through the woods, played music, and made noise, sound recordings, and movies. When the Dead showed up for the first time the Acid Tests really came together. They went from house party to publicized events that took place around California, including on the campus of San Francisco State University and a Unitarian Church in Los Angeles, and beyond. The Dead also began to formulate their core creative ethos. The Acid Tests were about facilitating the freedom to experience the awareness acid had unlocked for Kesey. At any given Test, all present were equals; there was no distinction of us and them, performer and audience, straight-laced or radical—anyone and everyone could “Turn on, tune in, drop out” (a Timothy Leary expression that became famous after he declared it at the Human Be-In in San Francisco in 1967, at which the Dead played). As Garcia remembered the Acid Tests in a 1988 interview, “Everybody got high and stuff would happen . . . Everyone there was as much performer as audience” (Garcia, 2013).

The Dead weren’t at every Acid Test—and sometimes even when they were scheduled to play they didn’t because the drugs got the better of them—but it was the blurring of the line between performer and audience and the freedom it permitted to all that was the greatest takeaway for the band at this early stage in their career. During the Tests they reveled in music’s power to possess both performers and audience; everyone joyously surrendering to rhythms and harmonies, and arguably touching on something even more profound that reaches back to the origins of theater and art, connecting the temporal realm with the mystic. This is what the Dead sought to share with their fans through music. It wasn’t about getting high; it was about creating a space to be free from convention.

Shares