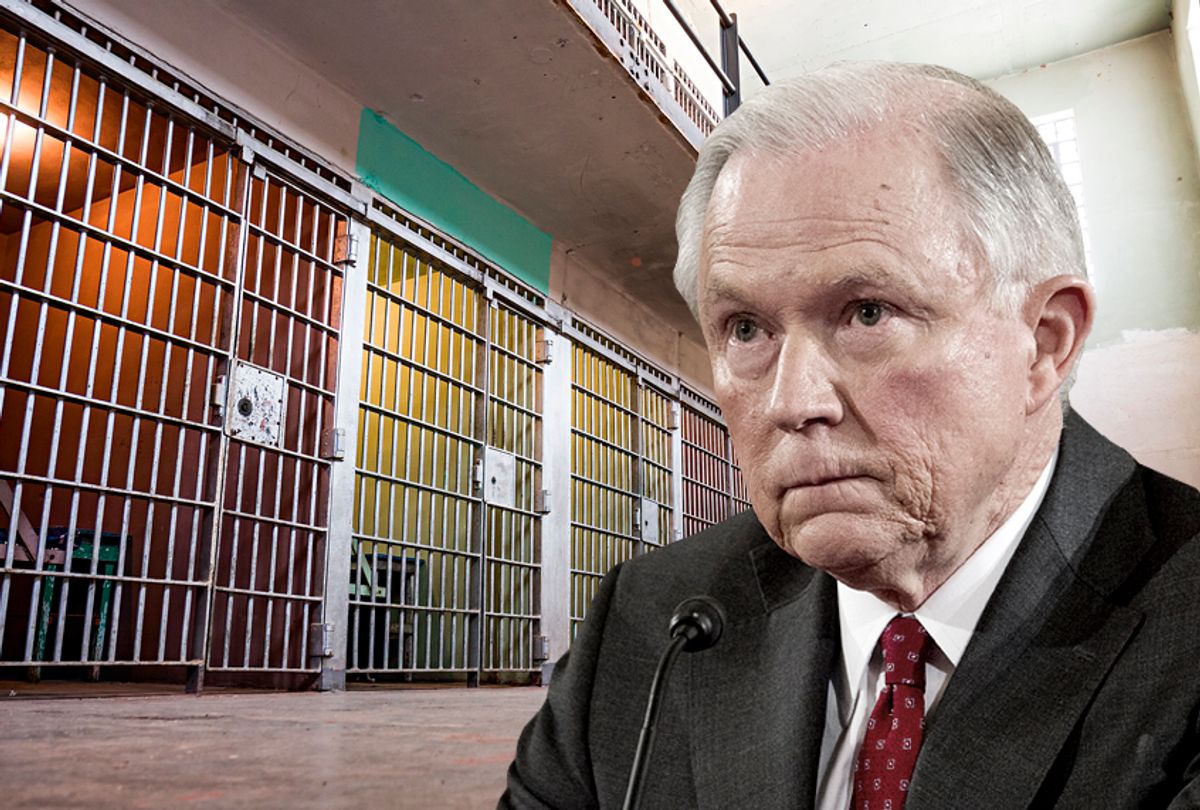

One day after President Donald Trump invited Republican lawmakers to the White House to celebrate the historic tax cuts they passed for corporations and wealthy business leaders, his attorney general, Jeff Sessions, quitely reinstated a draconian policy that effectively serves as a regressive tax on America’s poorest people.

A symbol of Victorian England’s inequitable nature made infamous by Charles Dickens, debtors’ prisons were banned in the United States in 1833. The Supreme Court has affirmed the unconstitutionality of jailing those too poor to pay debts on three different occasion in the last century, finding that the 14th Amendment prohibits incarceration for non-payment of exorbitant court-imposed fines or fees without an assessment of a person’s ability to pay and alternatives for those who cannot. “Punishing a person for his poverty” is illegal, the Court said. Yet in recent years the modern-day equivalent of debtors' prisons have returned, as cities have grown to rely on a punishing regime of fines and fees imposed on their own residents as a major stream of revenue.

Routine traffic tickets or even overdue student loan payments can set off a cycle of debt that also includes the suspension of a driver’s license or professional license and, in some cases, jail time. A suspended driver’s license makes it nearly impossible to get to work. When a person can’t pay, courts add more fines on top of the original. If those fees aren’t paid, a jail sentence is imposed. Incarceration is also often meted out to low-income defendants facing misdemeanor charges who cannot afford to pay bond ahead of a court date. It should come as little surprise that the policing tactics that have been enacted to generate revenue through this debtors’ system disproportionately impact people of color.

The protests in Ferguson, Missouri, following the shooting death of Michael Brown brought national scrutiny to the practice. Ferguson police sought to advance the “city’s focus on revenue rather than ... public safety needs,” an investigation by the Obama-era Department of Justice found. Ironically, the judge who most frequently sent Ferguson residents to overcrowded prisons for their petty fines not only personally benefited from the system — he moonlighted as a both a prosecutor and a private attorney when he was not sitting on the bench — but also owed more than $170,000 in unpaid taxes. A 2014 Washington Post investigation found that some towns in Missouri derived 40 percent or more of their annual revenue from the hefty fines and fees collected by municipal courts.

This routine incarceration of poor people attracted the attention of the Obama administration, which eventually issued a guidance advising courts across the United States against “slapping poor defendants with fines and fees to fill their jurisdictions’ coffers.” The March 2016 letter did not, however, threaten any specific enforcement action for those who ignored it.

Apparently less concerned with the plethora of jurisdictions effectively funding their operations on the backs of their poorest residents, Sessions explained that he sought to do away with “the long-standing abuse of issuing rules by simply publishing a letter or posting a web page.” After ordering a reform task force to identify “existing guidance documents that go too far,” the attorney general revoked more than two dozen such documents going back to 1975 on various topics, including a Reagan-era “industry circular” that stated it was illegal to ship certain guns across state line. He also issued a memo last month barring the Department of Justice from issuing nonbinding guidances.

“Congress has provided for a regulatory process in statute, and we are going to follow it,” Sessions said in a statement. Most, but not all, of the guidances were enacted under the Obama administration.

Sessions' move, while little noticed in the mainstream press or by the public, has already proven unpopular.

“These monetary punishments do nothing to protect the community while placing an unfair and unjust burden on people of lesser means,” wrote American Bar Association president Hilarie Bass in a statement.

“This latest action must be viewed alongside other actions taken by the attorney general to turn back the clock on civil rights compliance across the country," said Kristen Clarke, president and executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Other actions she cited included "abandoning use of consent decrees as a vehicle for promoting constitutional policing practices, reversing positions in pending civil rights cases and bringing federal civil rights enforcement to a virtual grinding halt.”

The author of the Obama-era guidance on debtors' prisons, Lisa Foster, who served as director of the Office for Access to Justice at the DOJ, criticized Sessions’ move. “The idea that the Department of Justice doesn’t care about the United States Constitution in courts is so wrong, and really unfortunate. It is a message that should not be sent, and has practical implications,” she told the Law&Crime blog.

But the letter’s co-author, Vanita Gupta, who served as head of the Justice Department’s civil rights division in the Obama administration, thinks Sessions is already too late to cause too much damage.

“The retraction of this guidance doesn’t change the existing legal framework,” she reminded The New York Times. “He can retract the guidance, but he can’t change what the law says.” Indeed, as the ACLU has noted:

Several weeks ago, a federal court ruled that New Orleans judges faced a conflict of interest in jailing poor people for unpaid fines because the judges control the money collected and rely on it for court funding. That same week, a federal court issued a preliminary injunction halting Michigan’s system for suspending driver’s licenses upon non-payment of traffic tickets due to constitutional concerns. And days later, the Mississippi Department of Public Safety agreed to reinstate the driver’s licenses of all drivers whose licenses were suspended for non-payment of court fines and fees.

In Missouri, where the troubling resurgence of debtors’ prisons first gained national attention, more than a dozen plaintiffs won a class action lawsuit filed against 13 St. Louis suburbs they accused of “conspiring” to “extort money” from poor African-American residents via traffic tickets in “a deliberate and coordinated scheme.” Even in Sessions' home state of Alabama, a Republican state legislator has sponsored legislation that would do away with debtors’ prison.

Fighting a losing battle seems to be Sessions’ forte. Just this week, the attorney general traveled to three states to declare that a crime wave is sweeping the nation.

“Let’s be frank, violent crime has been increasing in Milwaukee and throughout America and it’s troubling,” he said in Wisconsin. "As attorney general, I am committed to combating the surge in violent crime and supporting the work of our police officers," he said the same day in North Carolina.

But a report released Wednesday by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University's School of Law indicates that he rates for overall crime, violent crime and murder are all projected to drop in the 30 largest cities in 2017. Even according to statistics released by Sessions’ own Justice Department in September, the violent crime rate remains at historically low levels.

Shares