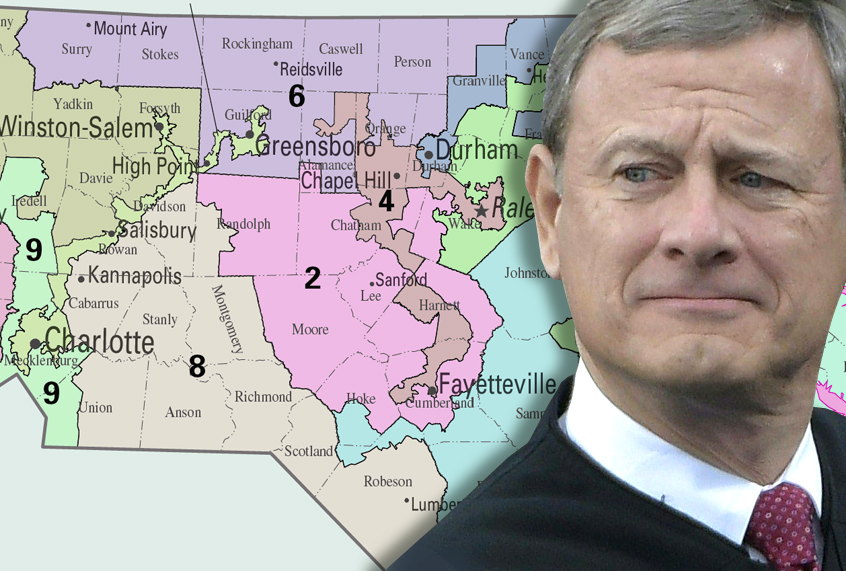

North Carolina is so narrowly and deeply divided that, last November, voters ousted a conservative governor in favor of Democrat Roy Cooper – but elected a Republican lieutenant governor as his partner. Donald Trump also carried the state.

Despite such competitive statewide results, however, North Carolina’s congressional races have become so one-sided that a professor at UNC-Chapel Hill compared the integrity of the electoral boundaries, unfavorably, with Venezuela and Iran.

North Carolina Republicans, well aware that, before Tuesday, no federal court had ever invalidated an entire congressional map for partisan gerrymandering, never bothered to mask their intent. They drew themselves a 10-3 edge, State Rep. David Lewis, a co-chair of the legislature’s redistricting committee, openly admitted, because “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats” and “I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats.”

Republicans have commanded a supermajority of North Carolina’s U.S. House seats all decade, including 2012, when Democratic candidates earned a majority of all votes. That year, Republicans won 48.7 percent of the vote, but 69.3 percent of the seats. Democrats have not managed to flip a single seat blue in any congressional contest on these maps.

This week, however, a panel of three federal judges took the historic step of striking down North Carolina’s “invidious” and “discriminatory” congressional map that “insulates Representatives from having to respond to the popular will” as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. They sided with Common Cause and the League of Women Voters in finding that the maps the GOP tilted violated the First Amendment, the Fourteenth Amendment and the Elections Clause. In a devastating and nearly 200-page rebuke written by Judge James A. Wynn Jr., they ordered that new, fairer districts for 2018 be drawn before the end of January.

On Thursday morning, the defendants appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court and also asked to pause the order for new maps. The justices are already grappling with two other partisan gerrymandering cases: Gill v Whitford (regarding GOP-drawn state assembly districts in Wisconsin) and Benisek v Lamone (a Democratic gerrymander of a single congressional district in Maryland). If the Court grants the stay — as it has in recent gerrymandering cases involving Wisconsin, Texas, and yes, North Carolina — pending clarity this spring on both Benisek and Gill, that could cloud the prospects for new maps this fall.

But Wynn’s ruling is playing a much longer game. Its true audience is a small one: conservative Supreme Court justices who have expressed their mistrust of modern statistics and social-science research methods. If even one could be persuaded, avoiding a 5-4 split, a potential ruling that reins in partisan gerrymandering would look less partisan and more small-d democratic.

When the Court heard oral arguments in the Wisconsin case three months ago, both sides focused on convincing Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote between four liberals appearing eager to find a solution to partisan gerrymandering and four conservatives wanting to keep the Court away from the thorny “political thicket” of adjudicating competing sets of partisan maps.

Chief Justice John Roberts suggested that new metrics designed to uncover a gerrymander — especially one known as the efficiency gap (EG) — were so confusing as to be “sociological gobbledygook.” He predicted that if the Court injected itself as the new arbiter of fair legislative maps using complicated criteria, even informed citizens would still believe politics guided the decision.

“Why did the Democrats win?” Roberts imagined an “intelligent man on the street” asking. “The answer is going to be because EG was greater than 7 percent, where EG is the sigma of party X wasted votes minus the sigma of party Y wasted votes over the sigma of party X votes plus party Y votes.” That man on the street, Roberts concluded, “is going to say that’s a bunch of baloney.”

Justice Samuel Alito had a similar concern. “Gerrymandering is distasteful,” he said. “But if we are going to impose a standard on the courts, it has to be something that’s manageable and it has to be something that’s sufficiently concrete.” In a reference to the efficiency gap, he asked, “has there been a great body of scholarship that has tested this?”

Wynn’s goal is to demystify these standards, cast doubt on those who won’t consider new ways of thinking, and assure judicial skeptics that the social science is both valid and tested. “There is no constitutional basis for dismissing” a partisan gerrymandering claim “simply because they rely on new, sophisticated empirical methods. … The Constitution does not require the federal courts to act like Galileo’s Inquisition and enjoin consideration of new academic theories,” he writes. “That is not what the founding generation did when it adopted a Constitution grounded in the then-untested political theories of Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau.”

What follows is a clear-eyed explanation of three new metrics that can reveal gerrymandering, and an easy to understand discussion of what the numbers show about North Carolina maps. In the end, Wynn shows, it’s not that any individual metric suggests that these maps are unfair or statistical outliers — it’s the collective weight of evidence when all of them do.

Wynn explains the two mathematical analyses that demonstrate how the GOP partisan advantage cannot be explained by the General Assembly’s legitimate redistricting objectives. One, by Duke professor Jonathan Mattingly, drew 24,518 simulated redistricting plans from a probability distribution of all possible North Carolina maps. Mattingly then applied the actual 2016 congressional vote, and found that a congressional delegation with 10 Republicans and three Democrats occurred in less than 0.7 percent of the plans.

Mattingly then tested whether the 2016 maps could have produced a pro-GOP bias from chance by making very slight changes around the edges of the districts. As Wynn observes, when Mattingly shifted as little as 10 percent of the district lines, a “very, very different partisan result” emerged that was “much, much less advantageous to Republicans.”

Wynn therefore feels comfortable finding an “intentional effort to subordinate the interests of non-Republican voters” given that 99 percent of Mattingly’s 24,518 plans “would have led to the election of at least one additional Democratic candidate.”

But he’s not finished there. Wynn couples Mattingly’s research with a similar computer-driven approach conducted by Dr. Joie Chen of the University of Michigan. Chen’s simulations, he observes, are based on very simple logic: If a computer draws 1,000 plans following traditional redistricting criteria, and the partisanship level of the actual maps lies outside that random range, it’s fair to conclude that something else drove the process.

Chen ran three different North Carolina simulations, each of 1,000 maps. He followed the non-partisan criteria supposedly governing the process. Not once did the computer create a plan that would elect 10 Republicans and three Democrats. His conclusion: “an extreme statistical outlier.”

Then, while Roberts and Alito complicated the efficiency gap, Wynn breaks it down, using a study by Dr. Simon Jackman of the University of Sydney: Subtract one party’s “wasted votes” that don’t help elect a candidate from the other party’s. Divide that by the total number of votes. A number close to zero reflects a plan that does not favor either side. In North Carolina in 2016, however, that number weighed in at 19.4 — the third highest in the state since 1972, surpassed only by 2012 and 2014.

Jackman then calculated the efficiency gaps for 512 congressional elections in 25 states between 1972 and 2016. North Carolina’s 2016 plan produced the 13th largest bias favoring the Republicans covering those 44 years. Of the 136 unique sets of maps studied by Jackman, North Carolina’s 2016 plan produced the fourth-largest efficiency gap. And when he compared it against the 2016 maps of 24 other states, it had the largest gap of any plan.

When the Supreme Court last took up partisan gerrymandering, in a 2004 Pennsylvania case called Vieth v Jubelirer, Justice Kennedy was already the swing vote and he wrote the key opinion. Kennedy sided with the conservatives and rejected the argument that the state had been unconstitutionally gerrymandered. But he wanted the Supreme Court to revisit the issue and remain open to a measurable standard.

“Technology is both a threat and a promise,” he wrote. “If courts refuse to entertain any claims of partisan gerrymandering, the temptation to use partisan favoritism in districting in an unconstitutional manner will grow. On the other hand, these new technologies may produce new methods of analysis that make more evident the precise nature of the burdens gerrymanders impose.”

The legacy of Common Cause and League of Women Voters v Rucho, then, may not come with new maps in North Carolina or Democratic pickups in this fall’s midterms, but rather if it convinces Roberts and Alito that today’s advanced math and supercomputers make gerrymandering possible — and also provide a manageable, non-partisan solution. Clock’s ticking: As the 2021 redistricting cycle approaches, that technology is only getting better.